Recent years have seen a marked decline in public support for major US political institutions, and the Supreme Court has not been immune from this trend. Michael J. Nelson and Alicia Uribe-McGuire write that this falling support could threaten the nation’s highest court, as legislators may have less of an electoral penalty from voters if they attack the Court. Studying Congressional lawmaking, they find that Congress is more than twice as likely to overturn a Supreme Court decision when public support for the Court is at its nadir compared to its highest level.

Recent years have seen a marked decline in public support for major US political institutions, and the Supreme Court has not been immune from this trend. Michael J. Nelson and Alicia Uribe-McGuire write that this falling support could threaten the nation’s highest court, as legislators may have less of an electoral penalty from voters if they attack the Court. Studying Congressional lawmaking, they find that Congress is more than twice as likely to overturn a Supreme Court decision when public support for the Court is at its nadir compared to its highest level.

Nearly every day, we are reminded that Americans’ support for their political institutions is in sharp decline. A majority of Americans do not approve of the actions of the current president, and even more are dissatisfied with Congress. The US Supreme Court has not been immune to this crisis of confidence; Gallup reported in July that only 37 percent of Americans have either “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of faith in the nation’s highest court.

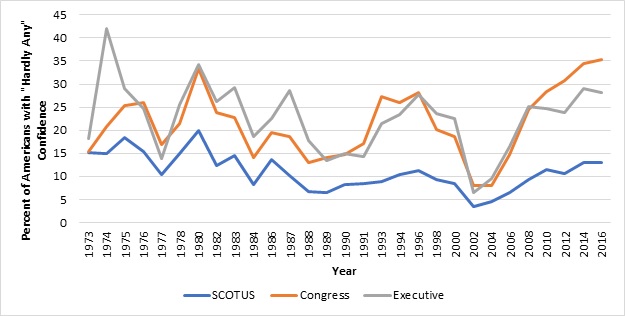

Figure 1 – Confidence in the American Federal Government

Note: Lines show the percentage of Americans who report having “Hardly Any” (rather than “Only Some” or “A Great Deal”) of confidence in each institution of the government. Data come from the General Social Survey.

These trends are not new. Figure 1 shows the percentage of Americans reporting “Hardly Any” confidence in each of the three branches of the federal government. These percentages come from the General Social Survey, a high-quality, nationally representative survey of the American people that has asked Americans their views about politics and government since the early 1970’s. Current confidence in Congress is lower than at any point in the past quarter-century, and the percent of Americans dissatisfied with each branch of the federal government has trended upward after an all-time low following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

Scholars have long known that public support has important implications for politics and government. Because the judiciary lacks both the power of the purse and the sword, it is uniquely dependent on public support; its decisions are more likely to be accepted and implemented when it is supported by the public. Similarly, it is more likely to be attacked by other branches of government when its public support is low.

We believe public support has an additional consequence: it affects policy change. Just as public support assists courts in the process of obtaining compliance with their decisions from other branches of government, it might also protect judicial decisions from nullification from these branches. In other words, just as the public’s satisfaction with the Court can reduce the extent to which Congress attacks the Court as an institution, it might also protect the Court’s decisions, stopping Congress from passing laws that override them.

Why would this work? Studies of legislative-judicial relations around the world have suggested that legislators are reluctant to attack popular courts because of the electoral connection binding legislators and constituents. When legislators attack popular courts, the argument goes, the public will rally to the judiciary’s defense, withholding their vote at the next election from those legislators who attacked the court.

And it does work. We studied the propensity of the US Congress to pass laws overturning US Supreme Court decisions. We thought that Congress would be strategic, waiting for an “opportunity” to strike out against the Court. If that is the case, Congress should be more likely to overturn US Supreme Court decisions when the Court’s public support is low. We tested this theory with a statistical analysis of congressional behavior between 1973 and 2010. During this time, Congress passed laws nullifying Supreme Court decisions 244 times. To measure the Court’s public support, we used the GSS survey data shown in Figure 1.

“The Entire World Is Crying, Supreme Court news conference to call for the reversal of President Trump’s travel ban on refugees and immigrants from several Middle East countries” by Lorie Shaull is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Our results show that the Court’s public support has a strong relationship with congressional action. The likelihood that Congress will overturn a given judicial decision increases by 109 percent as the Court’s public support changes from the lowest level we observe to the highest level in our data. This is a powerful role for public support to play!

Public support, of course, is not the only factor that predicts congressional overrides, and we predicted that the electoral calendar would also predict them. It does: Congressional overrides are 256 percent more likely in election years than in years in which Congress does not stand for election.

Perhaps most surprisingly, we find this evidence in the absence of a relationship between the level of ideological disagreement between Congress and the Court in its decision to override a given decision. This is somewhat puzzling, but it demonstrates the multifaceted process underlying congressional decision-making. Congress may want to overturn a given Supreme Court decision, but the internal politics of the institution, coupled with the public’s varying support for any given decision, make ideological disagreement an underwhelming factor in predicting congressional action.

Our results underscore the importance of the public for a well-functioning judiciary. Not only is the public’s support essential for the Court to achieve initial compliance with its decision, but continued high levels of public support help those decisions stay on the books. In an era in which confidence in the Court is on the decline, we predict a period of marked instability in American judicial politics and policy.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Opportunity and Overrides: The Effect of Institutional Public Support on Congressional Overrides of Supreme Court Decisions’, in Political Research Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2A5hlDb

About the authors

Michael J. Nelson – Pennsylvania State University

Michael J. Nelson – Pennsylvania State University

Michael J. Nelson the Jeffrey L. Hyde and Sharon D. Hyde and Political Science Board of Visitors Early Career Professor in Political Science, Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science, and Affiliate Law Faculty at Pennsylvania State University. He researches and teaches about political institutions, with particular attention to state judicial politics and public evaluations of judicial institutions in the United States and Latin America.

Alicia B. Uribe-McGuire – University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Alicia B. Uribe-McGuire – University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Alicia B. Uribe-McGuire is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her research interests focus on American political institutions, especially the relationship between the judiciary and other political actors.

There was a time not so long ago that justices were nominated for their experience and wisdom; rather than appeals court experience; and youth so that they are on the court for 30-40 years