Since 2010’s Citizen’s United Supreme Court decision, there has been increasing concern over the role of spending on elections from groups outside of the Republican and Democratic parties. There has been particular focus on outside spending on more extreme candidates, which could help to increase political polarization. In new research, Robin Kolodny and Diana Dwyre map the organizations which make up parties’ extended networks and those which are outside of them. They find that most non-party groups are inside parties’ extended networks, and tend to work towards their goals, rather than towards unseating establishment candidates.

Since 2010’s Citizen’s United Supreme Court decision, there has been increasing concern over the role of spending on elections from groups outside of the Republican and Democratic parties. There has been particular focus on outside spending on more extreme candidates, which could help to increase political polarization. In new research, Robin Kolodny and Diana Dwyre map the organizations which make up parties’ extended networks and those which are outside of them. They find that most non-party groups are inside parties’ extended networks, and tend to work towards their goals, rather than towards unseating establishment candidates.

With less than five months to go before the 2018 midterm congressional elections, observers and scholars begin to turn their attention to “handicapping” the outcomes. Clearly, there is much to say about voters’ opinions of President Trump and how that could influence the elections. But after noting the national mood, many analysts will immediately turn their attention to the candidates and their resources. Are so-called outside groups, such as Super PACs, directing resources to ideologically extreme candidates and, as some scholars have suggested, contributing to polarization? Are these non-party groups helping to elect candidates who are loyal to the groups’ agendas rather than candidates preferred by party leaders and politicians focused on winning? In new research, we find that, on the whole, these groups tend to support their party’s agendas.

Interest group, Super PAC, and even political party independent spending is often treated as a cause for concern. For many, campaigning by any person or group beside the candidates seems to taint the process. Our recent research questions the idea that group spending is problematic because many observers may have misinterpreted what it means to spend “independently” of a candidate. We evaluate candidates by their party affiliation, experience (governmental or otherwise), and the expected competitiveness of their race. Competitiveness is based in part on a candidate’s ability to raise money and the likelihood of “outside” groups spending on the race for or against the candidate.

In our work we use the theory of the extended party network (EPN) that political parties should not be viewed as institutions with well-defined boundaries, but rather as networks of affiliated actors that include party elected officials, candidates and leaders, as well as allied non-party groups and activists. We have argued previously that political parties “orchestrate” other actors’ activities in elections. To combine our view of party centrality with the unbounded nature of the extended party network, we analyzed the campaign finance activities of parties and groups active in both primary and general elections for the US House of Representatives in 2014. Although the parties generally stay out of nomination battles, we expected to find that groups considered part of the extended party network help to nominate party-preferred candidates against groups outside of the EPN (which are more independent), which may be attempting to elect more extreme candidates.

“ABAMarch-SEIU Local 73-IMG_0543” by SEIU is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0

Mapping party networks

We also expected to find that some partisan groups are on the party team, whereas others are not. Those groups on the team do not work against the party’s electoral strategy, which may in fact be to support more moderate candidates. We utilize network analysis to examine the connections between and among each party’s congressional campaign committees and the group or groups we expect are inside the party’s EPN and the group or groups we expect to be outside the EPN. The partial networks we examine reflect the most important spenders in House elections in terms of money contributed and races supported.

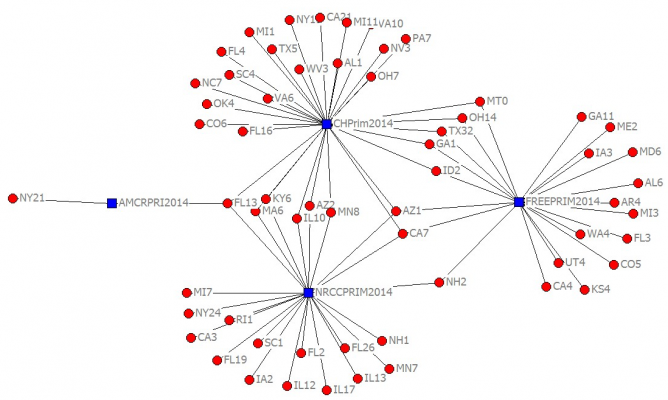

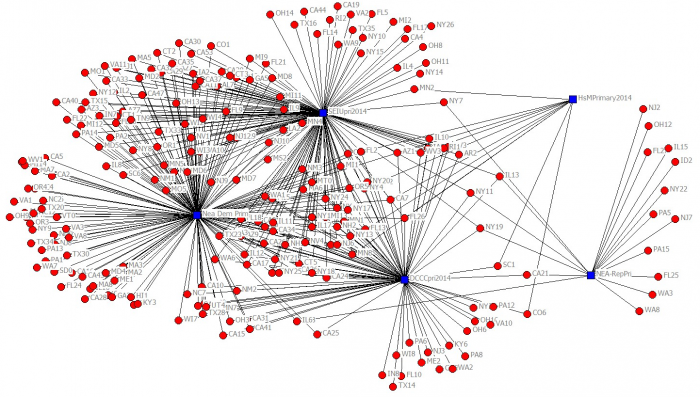

For the Republicans, we examine the National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC) and two groups we expect to be inside the party’s network, the US Chamber of Commerce (the leading business organization interest group) and American Crossroads, a self-identified Republican Super PAC. We compare this partial network with one group we expected to be outside of the Republican extended party network, the Tea Party Super PAC FreedomWorks for America.

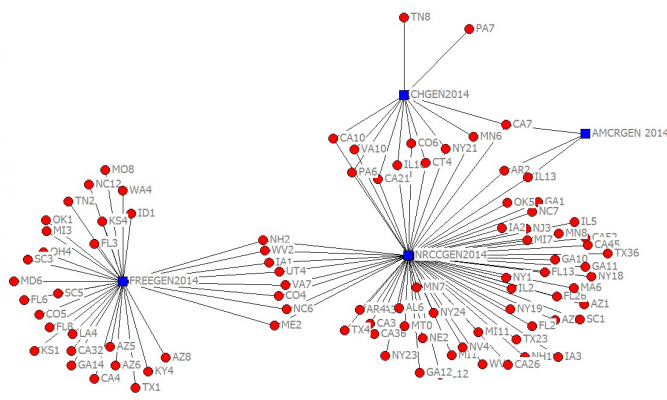

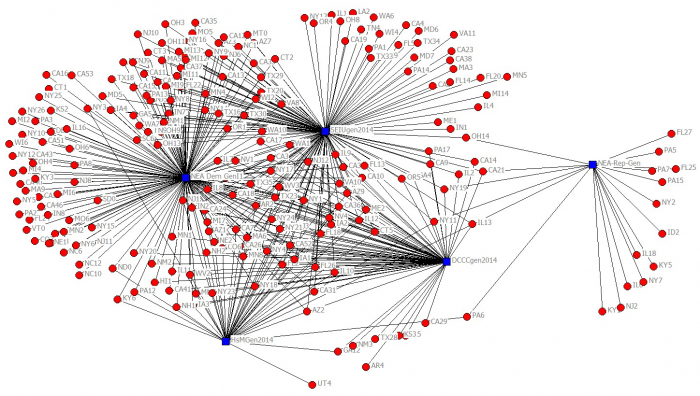

For the Democrats’ network, we examine the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) and the House Majority PAC, a super PAC dedicated to “helping Democrats win seats in the House.” We compare this hypothesized party network (DCCC and House Majority PAC) with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and the National Education Association (NEA), liberal labor unions that we expect might favor candidates to the left flank of the party than more mainstream Democratic Party–allied organizations. We thought that the SEIU and NEA may be outside the Democratic EPN because we expect that their distribution of campaign spending might not fully align with the Democratic Party’s as they frequently work to pursue both more left-leaning policy goals and access to key lawmakers across multiple congressional districts.

Using network analysis, we found that while the Tea Party was clearly outside the Republican Party network, its presence created a counter mobilization of another allied Republican group, the US Chamber of Commerce. In instances where the Tea Party made trouble for an establishment candidate in the primaries in particular, the Chamber vigorously opposed their efforts in favor of party-backed candidates (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 – Republican Primary Election Network 2014

Figure 2 – Republican General Election Network 2014

We did not find splits among any of the network actors in the Democratic Party network with the small exception of the NEA’s spending to help a small number of Republican candidates (see Figures 3 and 4). We see this as evidence of its access strategy, and because these were not races that Democratic candidates might have won, the NEA can still be considered more aligned to the Democratic Party than not.

Figure 3 – Democratic Primary Network 2014

Figure 4 – Democratic General Election Network 2014

Although partisan polarization in Congress is certainly real, and non-party groups may have helped elect some antiestablishment candidates in past elections, we are not convinced that the increase in non-party group independent spending because of the 2010 Citizens United Supreme Court decision is a major contributor to congressional polarization. As others have argued and our analysis here suggests, most non-party groups are partisan groups, and most of them are decidedly inside the parties’ extended party networks. Indeed, in 2014, the GOP extended party network responded to challenges from its extreme flank. Thus, while party election spending may not make up as large a portion of all spending in House elections as it once did, each party’s EPN appears to be pursuing the party’s goals, with much less spending aimed at unseating establishment candidates.

- This article is based on the paper “Convergence or Divergence? Do Parties and Outside Groups Spend on the Same Candidates, and Does It Matter?” in American Politics Research 46 (3): 375-401.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2NQSAfX

About the authors

Robin Kolodny – Temple University

Robin Kolodny – Temple University

Robin Kolodny is a professor and chair of the department of Political Science at Temple University. She was a 2008-2009 Fulbright Distinguished Scholar to the United Kingdom at the University of Sussex. In 1995, she was an American Political Science Association Congressional Fellow. She is the author of Pursuing Majorities: Congressional Campaign Committees in American Politics, and has collaborated with Diana Dwyre previously on articles and book chapters on campaign finance and political party organizations.

Diana Dwyre – California State University

Diana Dwyre – California State University

Diana Dwyre is a professor of Political Science at California State University, Chico. She was the 2009-2010 Fulbright Australian National University Distinguished Chair in American Political Science at Australian National University in Canberra, Australia, and the 1998 Steiger American Political Science Association Congressional Fellow. She has authored and co-authored two books and numerous articles and book chapters on political parties and campaign finance.