Big data and advanced analytics allow us to justify investment in social media, just like with other investments, write Witold Henisz, Dhruv Malhotra and Robin Nuttall.

Big data and advanced analytics allow us to justify investment in social media, just like with other investments, write Witold Henisz, Dhruv Malhotra and Robin Nuttall.

Could a single tweet destroy your company? Just a few years ago, a question like that might have seemed absurd. But now that possibility is something that executives and investors around the world are increasingly thinking and worrying about. Perhaps the most prominent evidence of this trend arrived at the start of 2018, when BlackRock’s Larry Fink laid out in his annual CEO letter what he believes organisations risk when they don’t get smart on social engagement. “Without a sense of purpose, no company, either public or private, can achieve its full potential,” he wrote. “It will ultimately lose the license to operate from key stakeholders.”

Fink isn’t alone. State Street and Vanguard now classify companies according to their approaches to external-affairs risk issues in their long-term strategies. And in fact, according to a recent report by the US SIF Foundation, the total US-domiciled assets under management using sustainable, responsible and impact investing strategies grew from $8.7 trillion at the start of 2016 to $12 trillion at the start of 2018, a 38 per cent increase. That’s 26 per cent — or 1 in 4 dollars — of the total US assets under professional management saying, “This stuff matters.”

Leaders are perhaps eager to respond, but it’s clear to us that boards and executives around the world haven’t felt as if they have a clear understanding of the actual risk and opportunity values residing in external engagement.

This is changing. Recent developments in big data and advanced analytics make it possible to assess and justify external engagement resource investments on the same basis as you would physical capital, brand capital, or technology resource investments.

Over the last five years, McKinsey has repeatedly helped industry leaders quantify the upside and downside value of certain external engagement risks. Here, we share two complementary, data-driven external engagement approaches based on that work: Outside-in approaches generate digital stakeholder and issue maps that leverage sentiment analysis and natural language processing. And inside-out approaches quantify expected value at stake from external engagement as a function of scenario outcomes.

We propose a measure of external value at stake (eVAS) to assess the value at stake from external engagement, and we further suggest that this more holistic metric should replace or complement traditional value at risk (VAR) analysis. To put it simply, if the net promoter score (NPS) is the one number you’ve needed to manage customer relations, eVAS is the one number you need now to manage social relations.

From VAR to eVAS

The concept of VAR was developed in the 1980s as a measure of investment risk. It estimates how much a set of investments might lose, given normal market conditions, over a certain period of time. “In the end, the greatest benefit of VAR lies in the imposition of a structured methodology for critically thinking about risk,” wrote University of California at Irvine Professor of Finance Philippe Jorion. We extend this concept in eVAS. Rather than estimating how much potential investments might lose, eVAS instead measures the investment value at stake given external engagement factors.

Our work across sectors typically finds about a 30 per cent downside eVAS, reflecting “value protection” risks such as taxes, price controls, market restrictions, and so on. And about a 20 per cent upside eVAS, reflecting “value creation” opportunities around deregulation, innovation, access to resources, employee engagement, and so on.

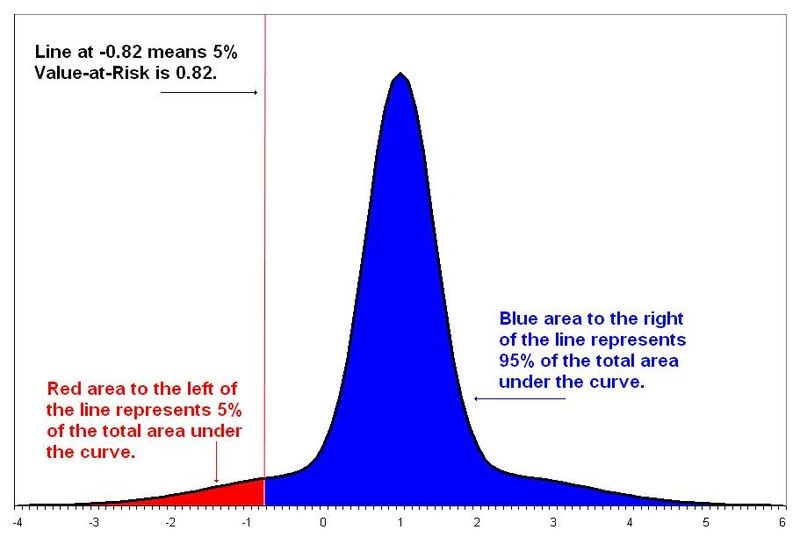

Figure 1 – A hypothetical profit-and-loss probability density function

Notes: The curve has mean one and standard deviation one, but fatter tails than a normal distribution. The 5% VaR point is 1.82 standard deviation below the mean, versus 1.64 for a normal distribution. Source: Wikipedia, by AaCBrown, public domain.

Professor Jorion also wrote that the “process of getting to VAR may be as important as the number itself.” We agree. The benefit of eVAS, like the benefit of VAR, lies in the creation of a structured approach to external engagement, thereby empowering company leaders to mitigate and maximise potential outcomes.

Outside-in approach

Stakeholder mapping used to be a paper or white-board exercise undertaken in a ‘war-room.’ Performed by government or community affairs experts in support of a company’s strategy, it involved scribbling phrases like “clout versus salience” on Post-it notes and then plotting them on a wall or bulletin board.

These sessions, while useful, typically did not fully integrate their findings with the core elements of the business. But this has all changed. Stakeholder opinion, relationships, and issues of concern can now be analysed digitally using big data, artificial intelligence, and network-mapping tools, producing quantified outputs to which financial and operational analysis and integrated strategy development can be applied.

In our experience, such a process has typically seen companies:

- Analyse (social) media, meeting reports, conversation logs, surveys, and more traditional government and community affairs outreach to locate and score cooperation/conflict expressed verbally or enacted by each stakeholder towards the firm and towards other stakeholders. That score would then be assessed on a single scale that measures the degree of cooperation or conflict.

- Construct dynamic stakeholder networks, from which they can extract the various summary statistics regarding the structure of the network including its density, hierarchy and cliquiness. These networks and summary statistics would then be disaggregated or analysed by stakeholder sector; geography; stakeholder type; and the stakeholder’s dominant engagement strategy.

- Use topic modelling and conceptual maps on the extant or expanded text corpus to identify issues associated with individual stakeholders. These stakeholders would include those across different sectors, geographies, and types, as well as stakeholders undertaking different engagement strategies.

The data from these activities can then be mapped along common frameworks and prioritisation schemes. This allows leaders to address issues of concern among several key external segments. At the same time, the process will also reveal any gaps between stakeholder perceptions and the organisation’s actual contributions to the stakeholder landscape.

Once these issues have been identified, companies will need to ascertain their material potential impact. This will require connecting the external engagement findings captured in the process above, and the data that supports them, with key financial and operational performance indicators of the project or enterprise.

Doing so effectively typically sees companies:

- Consider a set of discrete material events stakeholders across all categories could activate that would influence either a) the probability of realisation or b) alter the revenue or cost impact of realisation.

- Assess the potential material impact on the likelihood or magnitude of the event either assuaging or aggravating stakeholders’ issues of concerns, based on the input and guidance of the manager responsible for these potential risks or opportunities.

- Calculate the potential material impact (eVAS) for the firm of addressing each issue of stakeholder concern and prioritise issues and stakeholder engagement accordingly.

- Highlight, in engagement with stakeholders, those tangible incremental efforts to address issues of concern that the company could take, as well as pre-existing contributions the company is already making to stakeholder issues of concern.

Once established, this system should be monitored to yield better estimates of key parameters over time along with continuous stakeholder data. Calculating eVAS allows managers to understand whether they are appropriately mitigating risks and can also guide spending on external affairs and sustainability. This gives investors the opportunity to buy shares of firms that are investing wisely in mitigation.

Inside-out approach

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) has now developed a Materiality Map, the use of which serves as a valuable first step in our inside-out approach to calculating eVAS. Leaders should explore SASB’s issues material relevant to their industry within the map, and then define a corresponding, relevant issue list for analysis.

Once that step is completed, we recommend that companies:

– Develop simple scenarios for key issues. For example, in the case of looming tax reform policies, companies could perhaps build downside cases of a 30 per cent tax increase, a neutral case of 15 per cent, and an upside case of no increase.

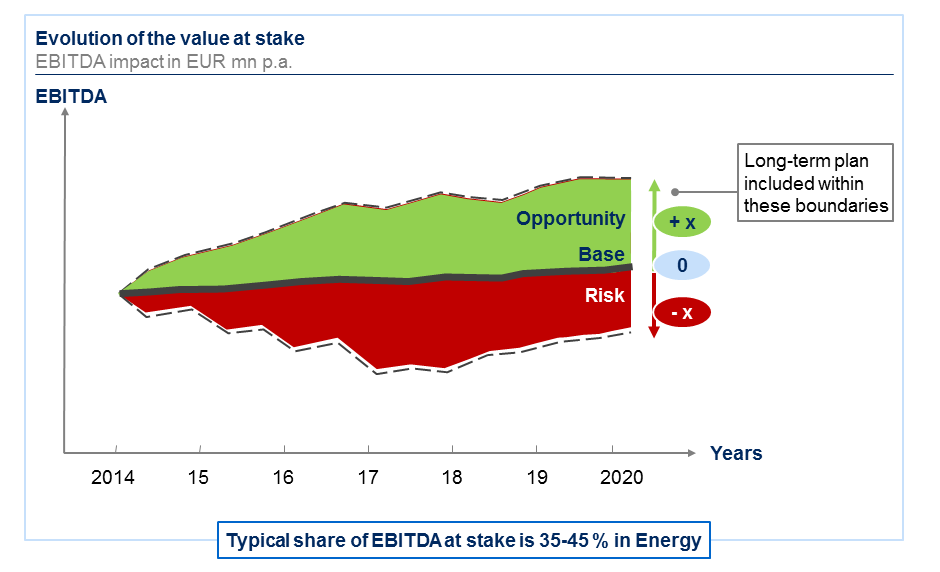

– Quantify the impact of different scenarios on EBITDA. (See graph below.)

Figure 2- The value at stake analysis provides a high-level assessment of the regulatory exposure throughout key topics

Source: McKinsey

– Synthesise the above results and determine highest value issues and opportunities. (See graph below.)

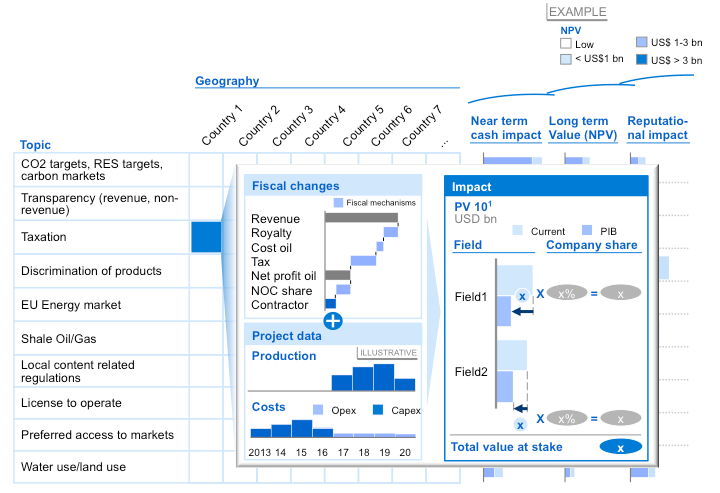

Figure 3 – What could a value-at-stake-based overview of external/regulatory issues look like?

Notes: Uses project data and fiscal changes to assess impact for each field from which company share is taken. Source: McKinsey; WoodMac Insights.

– Link these high eVAS issues to specific stakeholders, and prioritise engagement strategies accordingly.

When properly and fully executed, both approaches complement each other, ensuring that issues and concerns identified in stakeholder analysis, along with material risks identified in the firm, are connected to external stakeholder analysis and engagement strategies.

Too often, however, such connections and feedbacks are missing, leaving external engagement to be isolated from core business operations to the detriment of each. Such detriment, we believe, is avoidable by following the methods we share here.

Conclusion

External engagement was once viewed as an art that supported corporate strategy and value creation behind the scenes. Thanks to recent developments in advanced analytics, artificial intelligence, and big data, our work has shown that managers can apply science to external engagement, providing the data that CEOs need to allocate resources and address not only value at risk, but also upside opportunity capture.

So, could a tweet take down your entire company? Perhaps. But based on what we’ve learned, it certainly doesn’t have to.

- The authors would like to thank John Wilwol for his contributions to this article. The stakeholder approach is elaborated upon in “Corporate Diplomacy” by Witold Henisz and “Connect: How Companies Succeed by Engaging Radically with Society “ by John Browne, Robin Nuttall, Tommy Stadlen.

- This blog post first appeared at LSE Business Review.

- Featured image credit: Image by Martin Grandjean, under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence, via Wikimedia Commons

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2RLqGHy

About the authors

Witold Henisz – University of Pennsylvania

Witold Henisz – University of Pennsylvania

Witold Henisz is the Deloitte & Touche professor of management in honour of Russell E. Palmer, former managing director at The Wharton School, The University of Pennsylvania. He received his Ph.D. in business and public policy from the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, and previously received an M.A. in international relations from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. His research examines the impact of political hazards on international investment strategy, including efforts by multinational corporations to engage in corporate diplomacy to win the hearts and minds of external stakeholders.

Dhruv Malhotra – McKinsey & Company

Dhruv Malhotra – McKinsey & Company

Dhruv Malhotra is an associate partner at McKinsey & Company. He advises corporate executives at technology and telecom companies on large strategic moves, especially mergers and acquisitions. He also leads McKinsey’s North America regulatory strategy service line. He has an MPA in economics and public policy from Princeton University and a BA in philosophy, politics and economics from Oxford.

Robin Nuttall – McKinsey & Company

Robin Nuttall – McKinsey & Company

Robin Nuttall is a partner at McKinsey & Company’s London office. He leads McKinsey’s work in regulatory and government affairs, and has served both regulators and corporates on strategy and organisation across a range of sectors and geographies including utilities (rail, post, airports, telecoms), consumer goods (food and beverage; grocery retailing), healthcare, travel (airlines, agency), and banking. Robin is the co-author with Lord Browne (former BP CEO) and Tommy Stadlen of “Connect: How companies succeed by engaging radically with society.” Robin holds an economics doctorate from Oxford, was a Henry Fellow at Harvard, and has masters and undergraduate degrees in economics from Cambridge.