Despite his claims to the contrary, the first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency has been one of legislative failure, as the recent government shutdown illustrated. Zachary Albert and David Barney argue that one reason for Trump’s difficulties in achieving his Congressional agenda has been his weak coalition of support within his own party. While Trump was able to gain the presidency because of a personal coalition of support for his populism, they write, this uneasy grouping has not transitioned into a policy coalition, something that most presidents need for their agenda to be a success.

Despite his claims to the contrary, the first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency has been one of legislative failure, as the recent government shutdown illustrated. Zachary Albert and David Barney argue that one reason for Trump’s difficulties in achieving his Congressional agenda has been his weak coalition of support within his own party. While Trump was able to gain the presidency because of a personal coalition of support for his populism, they write, this uneasy grouping has not transitioned into a policy coalition, something that most presidents need for their agenda to be a success.

Most media commentators have characterized the recent government shutdown as yet another high-profile policy failure under the Trump administration. Indeed, Trump’s Congressional agenda has often floundered (e.g. Obamacare repeal) or failed to materialize (e.g. infrastructure spending), with the President often relying on Executive Orders to unilaterally implement his agenda.

Pundits point to a number of factors to explain Trump’s legislative failures, including his negotiating tactics, self-inflicted “missteps”, and Democratic obstructionism. Our research, however, points to a more fundamental explanation for Trump’s faltering agenda: a weak coalition of support in the Republican Party.

Presidents require support from a diverse but unified policy coalition to win elections and govern effectively. Historically, electoral and policy coalitions have overlapped substantially. Our research, however, finds that Trump was able to win the 2016 election without diverse support from key Republicans who wanted specific government policies enacted – what scholars call ‘policy demanders’. As a result, he often lacks the unified support needed to implement his agenda, leading to frequent legislative failure on issues that divide the Republican Party.

Electoral and Policy Coalitions Usually Go Hand-in-Hand

Key members of a political party are often able to elevate widely supported candidates before citizens actually cast their votes. During this pre-primary period (or the “invisible primary”), candidates signal their viability by competing for endorsements, campaign funds, and media appearances. When various party actors and interest groups converge around a preferred candidate and grant them access to these resources, this sends signals to party voters that the candidate is electorally viable and ideologically acceptable.

Most successful candidates have assembled diverse coalitions that support their run for office. During his White House transition period in 2008, Barack Obama drew support from Democratic affiliates including party insiders, liberal advocacy groups, environmental activists, and labor unions. This electoral coalition also resembled the policy coalition that supported Obama in his early election efforts. On issues like healthcare reform and cap-and-trade regulations, Obama had a ready-made coalition of actors who guided and encouraged his policy agenda.

Indeed, the reason these outside actors get involved in presidential nominations is because they seek policy outcomes. They align behind the candidate they believe will pursue their diverse agenda once in office. In other words, electoral coalitions transition into legislative coalitions, and historically presidents have worked to implement the priorities of the different people and groups that helped them win office.

Trump’s Fragile Electoral Coalition

Our research suggests that Trump did not assemble this consensus support within the Republican Party. We examined his support throughout the campaign by focusing on the reasons actors offered when they endorsed Trump, using this information to map out his electoral coalition and the policy demands they had.

“Trump and Palin at ISU – 1/19/2016” by Alex Hanson is licensed under CC BY 2.0

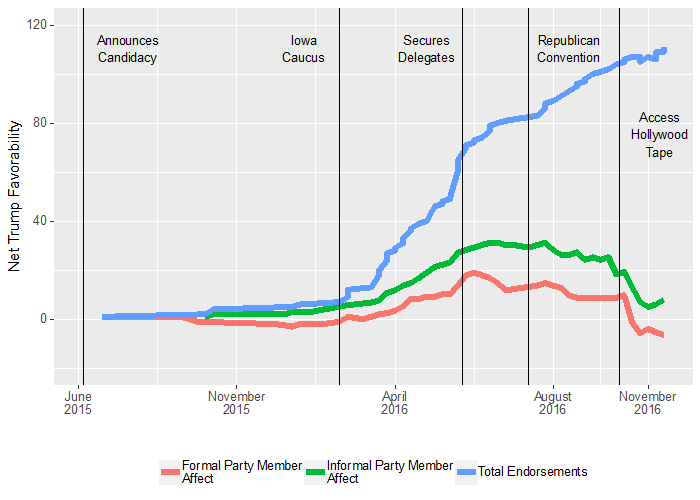

We find that traditional party actors largely abstained from endorsing Trump during the invisible primary. This can be seen in Figure 1, which tracks the number of endorsements (minus the number of actors opposing Trump) amongst formal party members (red line) and outside party actors (green line). The figure suggest that, prior to the Iowa Caucus in February 2016, more formal party members opposed Trump than supported him. In fact, only twelve actors endorsed Trump before Iowa. This group – which includes former Alaska Governor and 2008 Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin, businessman Carl Icahn, and professional basketball player Dennis Rodman – does not resemble the diverse network of party insiders who helped select prior nominees. And, these endorsers did not support Trump for his electoral viability or traditional Republican priorities, but rather for his populist messaging, business background, and national security rhetoric.

Figure 1 – Cumulative “affect” towards Trump amongst formal and informal party members.

Note: Cumulative affect is calculated by counting the total number of endorsements (valued at 1), criticisms (valued at -0.25), and withdrawn endorsements or outright opposition (valued at -1). Formal party members include any current or former politicians, while informal party members include interest groups, public or religious figures, media outlets, businesspeople or companies, and military figures.

Trump, then, did not emerge from the invisible primary with strong, diverse support from policy demanders. Rather, he assembled an unconventional and rather weak “personal constituency”, never amassing sincere and substantial support from diverse actors within the Republican Party. Although he ended the election with 117 endorsements, only one quarter of these were for policy reasons (mainly immigration and his stance on Islamic extremism). Instead, most (45 percent) endorsed him for personal reasons, often despite the fact that they opposed particular policies he advocated.

Others (29 percent) endorsed Trump for pragmatic reasons, namely the fact that he was “not Clinton” and that they would “support any Republican”. Many of these pragmatic supporters were party insiders like House Speaker Paul Ryan and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, but their support was very shallow. These insiders were most likely to criticize Trump’s temperament and policy positions, though most continued to support the candidate in the name of partisan unity and electoral necessity.

Elections Have (Policy) Consequences

The fact that Donald Trump was able to win the presidency without deep support from Republican affiliates has implications for his ability to govern. If electoral coalitions transition into policy coalitions, Trump’s legislative agenda is supported by a shallow and unorthodox mix of allies.

It is no surprise, then, that Trump has failed to pass policies, especially those that divide the traditional Republican coalition. In attempting to repeal the Affordable Care Act, for example, Republican Party divisions between business interests and ideological purists prevented successful legislative action. Having failed to unite these diverse elements of the party during the 2016 election, Trump similarly failed to find consensus support for an Obamacare alternative. The same could be said of Trump’s immigration policies, which divide Republican business interests from nationalists.

Trump’s few major policy successes are the exceptions that prove the rule. On tax reform, Trump inherited a strongly unified Republican coalition that had sought to lower taxes for decades. This diverse coalition rallied its resources to advocate for the policy and build public support, even if they had not supported Trump during the primary.

Similarly, Trump has enjoyed success in replacing Supreme Court justices with conservative picks. In these instances, Trump actually worked to assemble a diverse coalition of supporters during the election. Many endorsers mentioned the open Supreme Court seat as a reason for their support of Trump and, once in office, Trump acted on this promise with support from these same actors.

Lessons for Trump and His Opponent

Trump clearly broke from the traditional mold with his 2016 victory. He emerged from a large field of candidates by appealing to a narrow and unorthodox constituency, dominating media coverage, and circumventing traditional fundraising circles. This means that Trump’s presidency currently rests on a fragile electoral and legislative coalition. These coalitions are the typical basis of support for a presidency, and absent them Trump has struggled to push through his policy agenda.

While he has managed to maintain his prominence amongst Republican voters, his support amongst elite actors is tenuous. We should be cautious about drawing inferences from this – Trump has defied expectations before – but it seems probable that any number of developments could further undermine Trump’s thin support coalition amongst party insiders.

Our findings also hold lessons for Democrats running in 2020. As the field of candidates grows, the possibility that one can emerge from the crowded primary without consensus support increases. This is why the heavy hand of party insiders is so important: they are meant to weed out unlikely and unacceptable candidates so that the eventually nominee can assemble broad-based support. A candidate without such support is likely to face the same difficulties in governing that have plagued President Trump.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The Party Reacts: The Strategic Nature of Endorsements of Donald Trump‘ in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2X43OD7

About the authors

Zachary Albert – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Zachary Albert – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Zachary Albert is a PhD candidate at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and will be joining the Brandeis University Politics Department as an Assistant Professor in Fall 2019. His work examines political polarization, party politics, and the relationship between political parties and outside groups. His research can be found at www.zackalbert.com.

David Barney – WarnerMedia Applied Analytics

David Barney – WarnerMedia Applied Analytics

David Barney is a Primary Research Scientist at WarnerMedia Applied Analytics. He conducted this research while earning his M.A. in Political Science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. His research can be found at https://davidjbarney.github.io/.