For two years following the 2016 elections, the Republican Party held the presidency, House and Senate, giving them near complete control over the legislative process. And yet those two years saw the failure of the Party to repeal Obamacare or to prevent multiple government shutdowns. In new research, Robert N. Lupton, William M. Myers and Judd Thornton examine the ideologies of key Republicans and Democrats, and find that the Democratic coalition is much more unified both in terms of general attitudes and specific policies aimed at addressing social ills, such as higher school spending and abortion rights. Republicans, by contrast, are a group dedicated to rhetorical goals such as limited government and freedom, but who have vastly differing opinions on specific policies and programs.

Popular and scholarly observers have endeavored to explain the surprising collapse of Republican efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act in 2017, and their inability to prevent a government shutdown late last year, as well as pushback from some in the president’s own party to his request to fund a wall on the US-Mexico border. Why have Republicans struggled to develop party unity?

We tested for potential intra-party divisions using data collected in 2000 and 2004—the most recent publicly available data of its kind—capturing the political attitudes of delegates to the national party conventions. The delegates are useful for our purposes because they act as party activists who shape party platforms and mass public opinion alike. We examined Democratic and Republican delegates’ attitudes toward ten issues in each year comprising the major policy domains in American politics: socioeconomic, cultural and racial. Then, we tested how unified each party was by using an existing measure that assesses how well a person’s identification as a “liberal” or “conservative” matches his or policy attitudes, in addition to several other statistical tests.

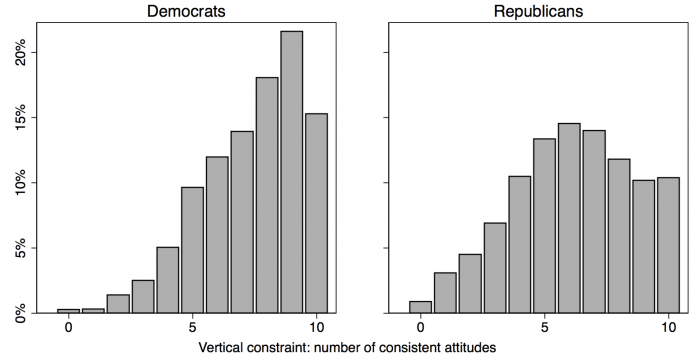

We focus here on the proportion of delegates within each party whose policy attitude aligns with his or her party identification. For example, among Democrats, an “ideologically correct” response to a question asking if government unemployment spending should be increased, decreased or remain the same would be “increased,” as the ideologically “liberal” preference is to increase government spending on social programs. The opposite is true for a Republican delegate. Figure 1 below shows the results of this analysis in the year 2000 (we show only the results for the year 2000 for clarity):

Figure 1 – Ideological alignment among Democrats and Republicans

The results are stark, as the Democratic coalition is significantly more unified. Indeed, more than 80 percent of Democrats offered an ideologically “correct” response to six or more of the ten policy issues that we examined, whereas 60 percent of Republicans responded correctly. Similarly, about 55 percent of Democrats, compared to approximately only 32 percent of Republicans, provided eight or more “correct” responses.

Credit: Voice of America [Public domain].

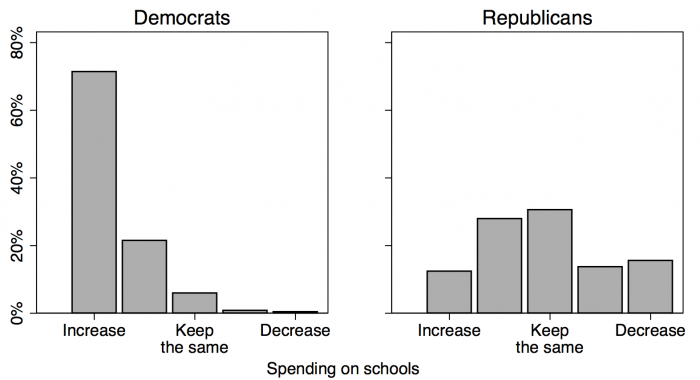

What about individual policy issues? As an example, we show below the distribution of responses toward public school spending. The Democrats were nearly unanimous in preferring that education spending be increased, whereas the Republican coalition was divided: More Republicans (40 percent) in fact preferred that spending be increased than decreased (30 percent).

Figure 2 – Attitudes towards school spending among Democrats and Republicans

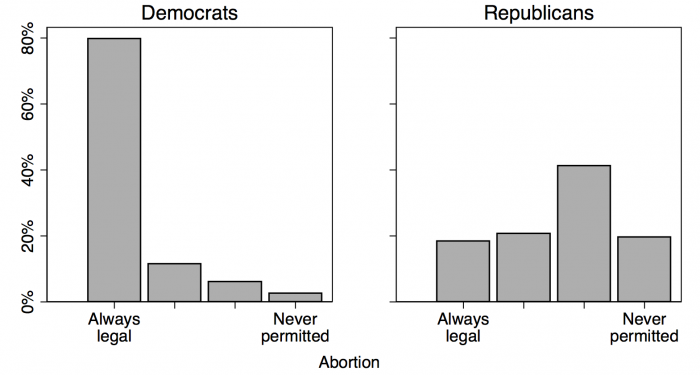

Education spending is one important social policy area, but what about a hot-button cultural issue? The graph below shows the same proportion of responses toward abortion:

Figure 3 – Attitudes towards abortion among Democrats and Republicans

Again, we observe that Democrats uniformly adopted a “liberal” position, as 80 percent of delegates responded that abortion should be “always legal,” and more than 90 percent offered an ideologically “correct” response. On the contrary, fully 40 percent of Republicans provided an ideologically conflicting answer, showing that Republican factionalism does not exist merely on economic issues or those pertaining to the size and scope of government. Rather, the Republican Party unites under one “conservative” ideological banner which includes activists with different views and elected officials who variously support elements of the social welfare state and liberal social policies.

Our results show that Republicans’ fractured governing coalition can be explained by the sharp contrast between party rhetoric and party ideology. Political parties are extended networks of party activists who all want something from government. Importantly, these activists may not share the same goals, but they develop an ideology—or common party brand—that allows each coalitional faction to pursue their individual goals as an alliance, as well as connect them to voters.

Other recent research shows that Republicans are best viewed as an ideological group dedicated to a principled commitment to limited government and traditional social arrangements. In contrast, that Democrats are a loosely connected coalition organized around support for a more active government, especially those designed to alleviate discrimination and inequality. Democratic and Republican elites also talk differently about politics. Democratic speeches, campaign advertisements and claimed electoral mandates all are defined largely by appeals to concrete policies and programs, whereas Republicans speak the language of ideological abstractions, framing their agenda in terms of “freedom,” “small government” and “American individualism.”

Republican elites speak abstractly because the broad language of “limited government” and “freedom” that appeals to conservative sensibilities successfully unites actors who do not share policy views. Many citizens who call themselves “conservative” nonetheless voice support for greater spending on many social programs, such as health care. We could see this type of “conflicted conservatism” in interviews with Tea Party adherents, whose skepticism toward government was often paired with support for various popular government entitlement programs, including Social Security and Medicare.

On the other hand, Democratic messaging focuses on specific policies because, despite being considerably more demographically diverse, Democratic elites nonetheless share the goal of using government programs to address social ills. We thus hypothesized that despite the apparent ideological coherence of the Republican Party based on analyses elite rhetoric, Democratic elites should be more unified at the level of policy attitudes. Our statistical tests confirmed our core expectations.

We should note that we replicated our analysis using data from the 2012 and 2016 American National Election Study (ANES). Although we could not investigate delegates’ opinions directly, we mimicked the activist sample by examining the attitudes of the most participatory citizens in the mass public. We found nearly identical results among these politically engaged citizens. As such, despite the president’s many ideologically charged policy promises, we anticipate that legislating will continue to be difficult not only because the 2018 election ushered in an era of divided control of government, but also because Republican party elites are themselves divided at the level of policy issues.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Party Animals: Asymmetric Ideological Constraint among Democratic and Republican Party Activists’, in Political Research Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2XVtJ06

About the authors

Robert N. Lupton– University of Connecticut

Robert N. Lupton– University of Connecticut

Bob Lupton is an assistant professor in the political science department at the University of Connecticut. He studies party coalitions and the role of core values, ideology and partisanship in public opinion and voting behavior, mostly in the American context. Find him on Twitter @GoBlueBob7.

William M. Myers – University of Tampa

William M. Myers – University of Tampa

Dr. William M. Myers is an Associate Professor of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Tampa. His research and teaching interests focus on American and comparative judicial politics and political behavior.

Judd R. Thornton – Georgia State University

Judd R. Thornton is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Georgia State University. His research focuses on public opinion and political behavior, with particular interests in partisanship, belief systems and ideology, and issues of measurement.

1 Comments