Religion in America is often political, and Black religious groups are no exception. But Black churches put forward a variety of political messages which can reinforce many different beliefs, write Eric L. McDaniel and Maraam Dwidar. In new research which examines how Black churches work to overcome White Supremacy, they find that adherence to one of three different sets of beliefs is linked to how Blacks interpret race issues. Both Black Liberation Theology and Prosperity Gospel adherents embrace Black Nationalism, while only Black Liberation Theology adherents are more likely to support Black Feminism.

Religion in America is often political, and Black religious groups are no exception. But Black churches put forward a variety of political messages which can reinforce many different beliefs, write Eric L. McDaniel and Maraam Dwidar. In new research which examines how Black churches work to overcome White Supremacy, they find that adherence to one of three different sets of beliefs is linked to how Blacks interpret race issues. Both Black Liberation Theology and Prosperity Gospel adherents embrace Black Nationalism, while only Black Liberation Theology adherents are more likely to support Black Feminism.

In 2017, the Bishops Council of the African Methodist Episcopal Church – the oldest independent Black denomination in America – released a statement condemning a number of President Trump’s Executive Orders. The statement called for members and allies to join them in thwarting the President’s “clearly demonic acts.” In direct contrast, leading up to the 2016 presidential election, Bishop Wayne T. Jackson of Great Faith Ministries in Detroit presented Trump with a Jewish prayer shawl he reportedly prayed and fasted over. Along with Bishop Jackson, several Black clergy rallied around Trump throughout the campaign, even once stating that his wealth signified he was “blessed by God.” In any other setting these divergent reactions to a president or presidential candidate would go not be major issue. However, the Black church symbolizes the Black quest for spiritual salvation along with their journey to achieve social and political freedom. By exposing variation in how they conceptualize Black political and social freedom, these Black religious leaders also exposed differences their conceptualization of salvation.

Historically, discussions of salvation in the Black church been intertwined with how to contend with White Supremacy. Among many slaves the discussion of salvation emphasized obedience and hard work, as slave holders wanted docile slaves and slave preachers hoped to protect Blacks from the harsh repercussions of challenging White supremacy. Similar religious rhetoric continued after slavery as preachers influenced by Booker T. Washington and William Hooper Council, emphasized the need for chastity, thrift, and hard work over political action. Rejecting this “false preaching”, figures such as Richard Allen and Frederick Douglass, argued salvation was achieved by ensuring equality for all. Relying on moral appeals, Allen and Douglass discussed how White Supremacy eroded the souls of both Blacks and Whites. Individuals, such as David Walker, Denmark Vesey, and Nat Turner, where more confrontational arguing God was on the side of Blacks and salvation could only be achieved by directly confronting and overthrowing White supremacy.

The rhetoric of Allen and Douglass are part of what is commonly referred to as the Social Gospel tradition, which emphasizes the link between social equality and salvation. It was the theological basis for the actions of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and is most commonly linked to the Black church. This tradition continues in the work of Rev. William Barber and his Moral Mondays protests in North Carolina.

Walker and Vesey are examples of the Black Liberation Theology tradition which draws parallels between the story of Christ and the Black experience, envisioning biblical figures as Black, and viewing the fight for Black freedom as a divine mission. This tradition is been linked to the more “radical” events in the Black experience, such as Bishop Henry McNeal Turner arguing God was a “Black man” and leading a migration to Africa post-Reconstruction. This tradition has been present in Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association as well as the Black Power Movement. Most recently, it gained national attention with Rev. Jeremiah Wrights criticism of the nation’s actions during the 2008 presidential election.

In contrast to these traditions that linked salvation to the freedom of others, the Prosperity Gospel tradition, contends salvation is achieved through individual piety. Specifically, the faithful are rewarded not just in Heaven, but also receive earthly rewards, such as, the accumulation of wealth and health. By appealing to the idea of a present and active God, discussions of God’s “favor” have been infused in the contemporary Black religious discourse. Several of its most prominent adherents have downplayed the need to fight White Supremacy and embraced candidates and policies perceived as antagonist to Black interests. This has led scholars to speculate the Black church has lost its mission with Eddie Glaude going as far as declaring the Black church dead.

“Church in Kentucky’s free town” by Don Sniegowski is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0

Our new research examines the extent to which adherence to these traditions is meaningful to how Blacks think about overcoming White Supremacy. Using a unique survey of Black Americans and original measures of the Social Gospel, Black Liberation Theology, and Prosperity Gospel belief traditions, we demonstrate adherence to each belief tradition is related to differences in how Blacks interpret race issues as well as how to overcome them. For instance, Social Gospel adherents express a stronger connection to other Blacks and perceive a power differential that benefits the rich over the poor. Prosperity Gospel adherents, on the other hand, are less likely to perceive a power differential between Blacks and Whites and the rich and the poor. Adherents of Black Liberation Theology identify with the oppressed by expressing higher levels of solidarity with Blacks and the poor, also they perceive a power differential the favors Whites over Blacks.

Moving from issues of solidarity and perceptions of problems, we assessed how these traditions related to overcoming these problems by focusing on three Black political ideologies: Black Nationalism, Black Conservatism, and Black Feminism. Black Nationalism reflects the belief Blacks should emphasize self-reliance, self-determination, and building sovereign local communities to protect the cultural, economic and political interests of Blacks. Black Conservatism, which is commonly viewed as the antithesis of the civil rights movement; emphasizes self-reliance while deemphasizing the role of race. It argues a strong work ethic and moral behavior will solve the problems of Black America. Finally, Black Feminism offers an expansive view of the “Race Problem” by emphasizing the intersectional nature of Black lives. Black Feminists argue that awareness of the multiple forms of marginalization, such as race, gender, and class, is the only way these problems will be solved.

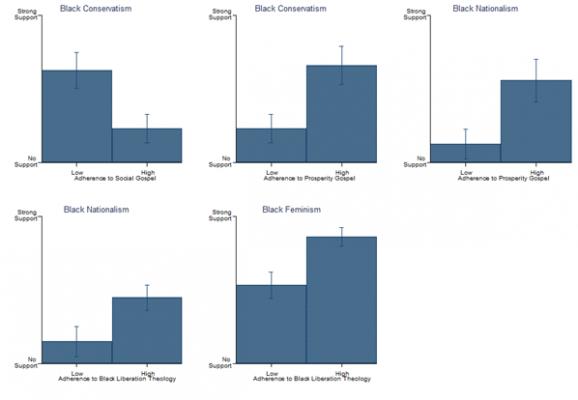

Our results, in Figure 1 below, show that the religious traditions are associated with these ideologies. Social Gospel adherents reject Black Conservatism, while Prosperity Gospel adherents embrace it. Interestingly, both Black Liberation Theology and Prosperity Gospel adherents embrace Black Nationalism. Support from Black Liberation Theology adherents was expected, but support from Prosperity Gospel adherents was not. Closer analysis finds that the self-reliance aspect of Black Nationalism is what draws Prosperity Gospel supporters to this ideology. Finally, only Black Liberation Theology adherents are more likely to support Black Feminism.

Figure 1 – Predicted support for Black political ideologies given adherence to religious traditions

These results indicate the need to pay attention to how Blacks define salvation, because it offers clues to how they will attempt to solve the “Race Problem”. An expansion of the Social Gospel signals continuing the strategy employed by the civil rights movement and traditional Black organizations, while the growth of the Prosperity Gospel indicates embracing piety and a non-racial perspective, while working with groups classically viewed as antagonistic to the Black cause. Finally, the expansion of Black Liberation Theology signals support for “radical” or expansive strategies. Black Lives Matter activists have rejected partnerships with Black churches because of their limited view of achieving Black equality making it obsolete in this new movement. However, these activists may find partnerships with churches that embrace Black Liberation Theology, which will allow the church to remain relevant in this new era of activism.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The Faith of Black Politics: The Relationship Between Black Religious and Political Beliefs’ in the Journal of Black Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ORocDH

About the authors

Eric L. McDaniel – University of Texas at Austin

Eric L. McDaniel – University of Texas at Austin

Eric L. McDaniel is an associate professor in the Department of Government at the University of Texas at Austin. He is a faculty affiliate of the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies and the Institute for Urban Policy Research Analysis. Finally, he is a faculty research associate of the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

Maraam Dwidar – University of Texas at Austin

Maraam Dwidar – University of Texas at Austin

Maraam A. Dwidar is a graduate student in the Department of Government at the University of Texas at Austin.

This is why Black Caucus members of the Green Party also have a hard time campaigning in black churches. They don’t fit our narrative of Black Feminism, because those beliefs were edited out of gospels, compared to non-canonical versions and African tradition.