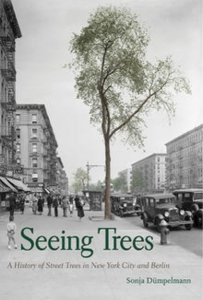

In Seeing Trees: A History of Street Trees in New York City and Berlin, Sonja Dümpelmann explores the role that street trees have come to play in our cities, focusing on different moments in their development and history in New York City and Berlin. Examining the specific social, political and cultural context that has shaped these cities’ urban forests, the book draws attention to these living reminders of our interconnections with the surrounding environment, writes Sierra Williams, and the opportunities and challenges of taking local and global action for something greater than our individual selves.

Seeing Trees: A History of Street Trees in New York City and Berlin. Sonja Dümpelmann. Yake University Press. 2019.

I find street trees in the city haltingly poetic. Walking down a crowded pavement with the sounds and smells of London pervading my senses, it is an absolute treat to come across a mature London Plane (Platanus x hispanica) or Linden (Tilia x europaea) or American Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) or even the occasional Cherry (Prunus spp) currently in blossom. Often these silent stalwarts have long preceded the London landscape I know and love. They blend amongst the cycle racks, rubbish bins and road dividers, but they also appear slightly out of place. Much to the chagrin of anyone I am walking with, I stop and stare with compulsion (and take a picture for ‘the gram’ because I am a good millennial) and consider what was the London that this tree experienced as a sapling? How many different species of bugs, fungus, bacteria and more have come across this tree – either in peace or hostility? How does a tree continue to survive the city? This question unearths the root of my interest in the matter: submerged in the interconnected complexity between urban and natural life, how can we all survive the city?

Interest in and caring for the trees in our crowded cities seem such a relatively recent preoccupation, no doubt inspired by the environmentalism of the 1970s (and for kids of the 90s, Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax) and further fuelled by the very real threat of climate change, toxic CO2 and pollution levels, rampant deforestation rates and the unrestrained urban sprawl of the twenty-first century. But Seeing Trees: A History of Street Trees in New York City and Berlin by Sonja Dümpelmann does well to swiftly rid us of the notion that city dwellers’ relationships with street trees is anything new, delving into the local politics, social struggles and everyday conversations surrounding trees in the newly-built environments of two rapidly expanding cities of the late 1800s and early 1900s. ‘We are in need of tree doctors, but not of tree butchers.’ This sentence captures succinctly the rhetoric of today’s sometimes light-hearted but often embittered battles on the part of local residents to protect street trees in densely urban areas from Sheffield to South London. It is then both encouraging and despairing to read this sentence written in response to the street management of the early 1900s in New York City.

What role do street trees play in our cities? Beyond generic figures of oxygen levels produced and cooling effects, this historical look at street trees provides a rich understanding of their social and political dimensions. The book explores the articulated value, needs and requirements of city trees over time, as well as the growing professionalisation and management of urban forestry during the Second Industrial Revolution. Both of these aspects have huge ramifications for how our urban spaces are still organised today. But what the book also does well is show implicitly that we haven’t really come very far in terms of ground covered – the social ramifications of managed urban spaces and the mechanisms for local control of these spaces (or lack thereof) are easily apparent today. The roots of our tree-faring conflict are buried in the rich soil of cultural approaches to how social life can and should be organised. Cultural clashes between tree professionals, city planners, human residents and the many other species that make up our cities.

Image credit: Trees of London @trees_london (Sierra Williams)

Image credit: Trees of London @trees_london (Sierra Williams)

Seeing Trees is structured in two parts with the first four chapters centred around New York City and the latter four focused on Berlin. Each chapter explores a certain time and place in the development of street trees with notable attention on a specific social, political and cultural context shaping the city’s urban forest. Urban forestry itself is a scientific, technological phenomenon. Techniques which include planting, pruning, shaping and hybridising species have been used in the service of modernity, essentially taming the natural world to fit our modern lifestyles. The conflicts outlined in the book are as much about the roles of trees in everyday life as they are the shifting role of technology.

The first two chapters provide a fascinating look at the emerging professionalisation of tree management and urban forestry, as well as the scientific management of cities as a whole. Readers interested in the field of urban forestry, urban planning or landscape architecture will find these chapters historically captivating moments in time. What stands out especially in these chapters is the sheer scale of data that needed to be captured to save early-twentieth-century NYC from a treeless future. The many photos, figures, maps, paintings and historical records of street trees throughout the book provide a rich depiction of the scientific development and aesthetic impact of the tree planting movement of the late 1800s and early 1900s.

From a Science, Technology and Society (STS) perspective, the New York chapters contain valuable insights on how Taylorism and the Technological Revolution shaped arborists’ appeals to the rational-scientific nature of tree selection and ‘efficient’ street planning, with positive and negative effects for the health of trees and residents alike. DDT and lead arsenate were indeed efficient for killing the insects spreading Dutch elm disease, but at what cost? Furthermore, the ideal street tree of the time bears awfully similar convergence with notions of the ideal worker: a push towards uniformity, resilience in harsh living conditions, an expectation of continual and rapid growth year-on-year, with a strong preference for those who could claim ‘native’ status.

Chapters Three and Four are particularly enlightening on the links between street trees and social movements focused on resistance and empowerment. In the UK at least, arboriculture as a practice and field of study is heavily weighted towards white male voices, so I cannot stress enough how refreshing it was to read about the role of women and African Americans in reclaiming their right to the city through tree planting and locally organised community development initiatives.

For example, Dümpelmann highlights the ‘Treeroots’ Initiative in the 1970s as a tangible, grassroots way for Brooklyn residents to address inequality, promote civil rights and encourage wider political engagement. Dümpelmann writes: ‘As a key tool of neighborhood transformation, tree planting was used for children’s nature education, community and identity building, and to rejuvenate the neighborhood and improve its living conditions’ (104). More than just a way to improve the physical natural landscapes of struggling urban areas, tree-planting activites were an effective ‘in’ for wider social justice and civil rights activism.

The Berlin chapters focus on the social context of rebuilding post-war Berlin and the differing approaches of urban planning in East and West Berlin during the Cold War, with a close look at how political ideologies shaped both tree management practices specifically, and indeed the approach to the city itself more generally. Due to the historical moment and juxtaposition of nature and the nascent modern city, the book is a great read for anyone interested in the cultural development and impacts of scientific management and political ideology in the framing of neoliberal efficient or socialist urban spaces.

I was very interested to read about the developments of and appeals to scientific research regarding the role of trees in cities, from the effects on climate to health to psychology, as well as sociological research on trees as design tools for improving social conditions. Chapter Four in New York and Chapter Six in Berlin each cover different ways that urban planners, tree specialists, resident groups and landscape architects approached, adapted and applied this evidence. It has always seemed to me a suspiciously feel-good hypothesis that planting trees throughout, for example, social housing developments can somehow immediately transform lives. By positioning specific evidence claims alongside the narratives of how this research has been applied in different ideological and material contexts, Seeing Trees provides a useful lens for understanding the value of trees beyond isolated instrumental improvements, rather seeing the unique placement of street trees as both public and private spaces that are ripe for fruitful social intervention. This argument therefore complements research by Frances E. Kuo et al on the wide-ranging positive effects and affect of exposure to green spaces (also discussed very engagingly in this Hidden Brain podcast episode).

Notably, the book has forced me to consider some of my strongly held assumptions relating to street trees. Does Ailanthus really deserve to be treated as a weed with such scorn and derision? Or is it actually the hangover of past prejudices rooted in anti-immigrant rhetoric that has little bearing on its actual ecological impact? And what makes an ‘ideal tree’ anyway? Is this not just human hubris and our need to minutely manage every facet of environmental outcomes, seeking a false sense of security in neoliberal uniformity? Finally, the perspectives shared in Seeing Trees underline for me why the urban forest is such an appealing concept – itself the culmination of contested ideas on our complicated, human-controlled, scientifically-managed, but unmistakably living cities.

Trees, and specifically street trees, in our urban and suburban settings are living reminders of our interconnected lives with the environment, reminding us of the opportunities and challenges of taking local and global action for something greater than our individual selves. But trees are also separate to the pace of our modern lives in a way that is so incredibly rare – both a public resource and a private benefit.

Related Media

- ‘The Secret Language of Trees’: To the Best of Our Knowledge podcast episode on how trees interact with each other and the species around them.

- ‘Our Better Nature: How The Great Outdoors Can Improve Your Life’: Hidden Brain podcast episode highlighting research on the social breakdown that occurs in areas without trees and greenery.

- The New York City Street Tree Map: resource of over 690,000 species and location information of New York City’s street trees.

- London Street Tree Data: resource of over 700,000 species and location information of London’s trees.

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2UN7L1H

About the reviewer

Sierra Williams – PeerJ

Sierra Williams is Community Manager at PeerJ, the open access publisher of biology, computer science and chemistry journals including PeerJ – the Journal of Life and Environmental Science. Sierra is co-author of Communicating Your Research with Social Media: A Practical Guide to Using Blogs, Podcasts, Data Visualisations and Video. She tweets @sn_will and shares pictures of London trees on Instagram @trees_london.

Find this book:

Find this book: