Politicians must often walk a fine line with their rhetoric in order to avoid offending important groups – and this need is no different where the “base” of their party is concerned. John V. Kane has previously found that when a politician actually works to upset their base, this can lead to more support from those in the opposing party, which could lead to more bipartisanship. In new research, he determines that partisans are attracted to stories about an opposing-party president antagonizing their base, revealing another way that the media are important in forming political opinions.

Politicians must often walk a fine line with their rhetoric in order to avoid offending important groups – and this need is no different where the “base” of their party is concerned. John V. Kane has previously found that when a politician actually works to upset their base, this can lead to more support from those in the opposing party, which could lead to more bipartisanship. In new research, he determines that partisans are attracted to stories about an opposing-party president antagonizing their base, revealing another way that the media are important in forming political opinions.

Social groups in the US (for example, Muslims, Latino immigrants, White nationalists, Feminists, and Evangelical Christians) play an enormous role in structuring our daily politics and political discourse. But despite their strong alignments with either the Democratic or Republican Party, these groups also present challenges for the parties.

One such challenge is that politicians perpetually run the risk of displeasing the groups that form the “base” their party. Though President Trump is widely noted for actively courting his base (for example, see here and here), other elected elites, including former President Obama, have been severely criticized for “alienating” their party’s base and plunging the party into disarray. More recently, witness US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s ongoing war of words with her party’s progressive wing.

There is, however, an under-appreciated consequence of this infighting. In past research – that I’ve also written about on The Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog – I find that these “base relations” have significant effects on the degree to which partisans trust, approve of, and would vote for a member of the opposing party. For example, when a politician upsets (rather than pleases) groups in her party’s base (which might include Evangelicals in the Republican Party, or African-Americans in the Democratic Party), partisans in the other party appear willing to regard this politician as, in effect, an “enemy of their enemies”. As a result, these partisans show greater political support for, and, even more surprisingly, greater willingness to compromise with her.

These results had little to do with actual policies. Base relations are powerful in their own right, I argue, precisely because of the fundamentality of social groups in American politics. When these groups enter clearly into the picture, partisans—contrary to conventional wisdom—actually start showing evidence of changing their minds. In short, if elected officials want any support from the other side, they can’t be all about that base.

Photo by Tomas Sobek on Unsplash

This set of results raises a couple of important questions, however: To what extent do media actually communicate this kind of information, and would partisans even bother to pay attention to it?

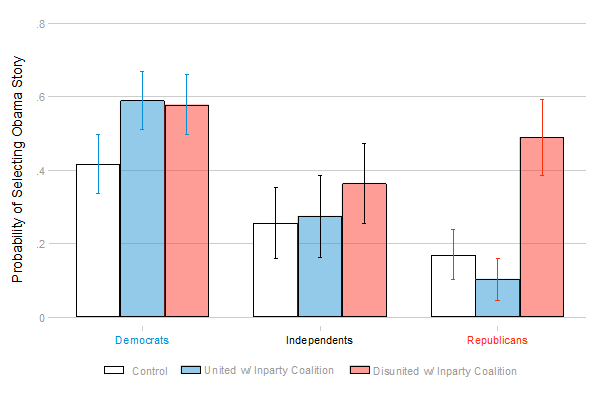

I explore both of these questions in a new study. On the question of whether partisans take notice of tensions between an executive and his/her party’s base, I designed two experiments—one involving former President Obama, and one involving President Trump—wherein these executives were reported to have either been united with a major group in their party, or disunited with this group. For Obama, the group was liberals; for Trump, it was conservatives.

A key finding to emerge was that partisans are relatively eager to read stories in which the opposing-party president upsets his base. For example, as Figure 1 shows, when given the choice between a news story about Obama or three other news stories about non-political content, Republicans were a remarkable 39 percentage points (124 percent) more likely to select the Obama story when it involved him alienating (rather than appeasing) his liberal base. No such pattern was observed among Democrats or Independents.

Figure 1 – Likelihood of selecting stories based on context

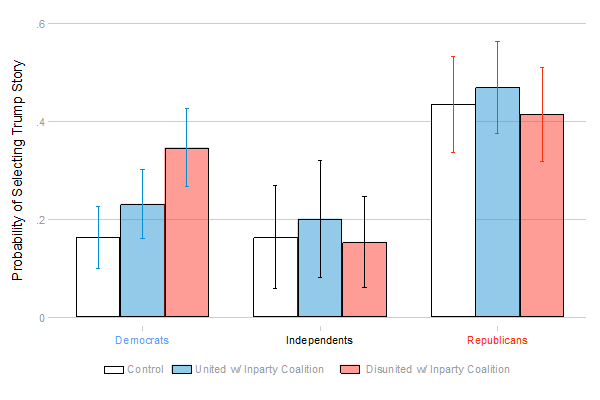

However, when it came to reading a news story about President Trump, Democrats exhibited behavior very similar to their Republican counterparts (Figure 2). That is, Democrats were significantly more likely to select a news story about Trump when it involved him upsetting his conservative base. Republicans and Independents, on the other hand, showed no such pattern of behavior.

Figure 2 – Likelihood of selecting Trump-based story based on context

Again, given the results of my earlier study on “base relations”, these findings suggest that the ways in which elites interact with groups in their party’s base can attract partisans’ attention, and substantially influence partisans’ attitudes toward them.

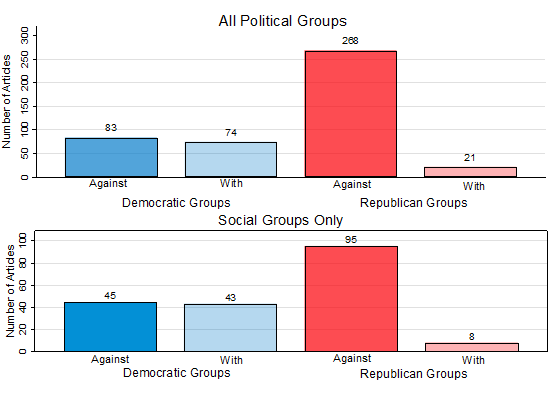

The second question, however, concerns whether mass media actually convey such disunity between an executive and his or her party’s base. I investigated this by conducting a large-scale content analysis of news articles published throughout the Obama presidency in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and the New York Post. In total, 1,360 unique articles were analyzed.

A number of interesting findings emerged from this study. Perhaps most importantly, the analysis revealed that it was not as though Democrats were usually reported to be supportive of President Obama: Whether looking at mentions of Democratic political groups as a whole in relation to Obama, or just mentions of Democratic social groups (which I found to be primarily ideological, class-based, and racial in nature), disunity in the Democratic Party was commonplace throughout the Obama presidency. In fact, my analysis found disunity to be slightly more commonplace than unity, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Article mentions and political unity

Republicans, on the other hand, were overwhelmingly reported to be opposed to President Obama. This pattern was again evident regardless of whether I examined Republican political groups as a whole, or only Republican social groups (which I found to be primarily ideological and class-based in nature).

In a broad sense, these content analysis results give us a window into how members of the public understand the parties, and political leaders in particular, in relation to prominent social and political groups.

More specifically, these findings echo the notion of a Democratic Party frequently in disarray, at least relative to the Republican Party (see also here). But, they also confirm that mass media commonly report on relations between elites and key groups in each party’s base. And, as discussed above, partisans care about, and even appear to base their political opinions on, these very party-group relations.

Our group-centric politics is not likely to disappear any time soon. Collectively, the results of my studies imply that, if our leaders want polarization to continue thriving, they should publicly please groups in their base while openly denigrating groups in the other party’s base, as President Trump has done with respect to several racial and religious minority groups aligned with the Democratic Party.

However, if leaders want to capture the attention of, and perhaps even a modicum of trust from, the other side, there are strategies available (albeit politically risky ones). Specifically, they can distance themselves from their party’s base, even if only symbolically. If executed well, members of the opposing party will notice, and are likely to meaningfully adjust their evaluations.

To be sure, there will be times when this is strategically unwise (during a political primary, perhaps). But, at other times, it may mean the difference between crucial legislation passing or dying in Congress or in state legislatures, with potentially enormous consequences for people’s everyday lives.

Clever political leaders, in other words, may be able to successfully capitalize upon the group-centric nature of our politics, cultivating the bipartisan political capital needed to enact legislation that can move the United States forward on a variety of critical fronts. Absent such efforts, partisans and politicians will no doubt remain perpetually mired in gridlock and focused on the next election, hoping to yield, at last, an unencumbered control over policymaking, only further enraging the other party in the process.

- This article is based on “Enemy or Ally? Elites, Base Relations, and Partisanship in America” in Public Opinion Quarterly and “Fight Clubs: Media Coverage of Party (Dis)unity and Citizens’ Selective Exposure to It” in Political Research Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2Y18p8N

About the author

John V. Kane – New York University

John V. Kane – New York University

John V. Kane is an Assistant Professor at New York University’s Center for Global Affairs. He recently completed his Ph.D. in Department of Political Science at Stony Brook University. His primary research interests include political psychology and behavior, and experimental research methodology. His research has been published in a variety of peer-reviewed journals, including the American Journal of Political Science, the British Journal of Political Science, Public Opinion Quarterly, Political Research Quarterly, and Presidential Studies Quarterly. More information can be found at his website, www.johnvkane.com. Follow him on Twitter @UptonOrwell