Despite progress in the 1960s and 1970s, the desegregation of US employment has largely ground to a halt. In new research, John-Paul Ferguson finds that, in addition, individual workplaces have actually become more segregated over the past three decades. They comment that until now, workplace segregation has been little-studied; their results show that society has made less progress in this area than had been assumed.

Despite progress in the 1960s and 1970s, the desegregation of US employment has largely ground to a halt. In new research, John-Paul Ferguson finds that, in addition, individual workplaces have actually become more segregated over the past three decades. They comment that until now, workplace segregation has been little-studied; their results show that society has made less progress in this area than had been assumed.

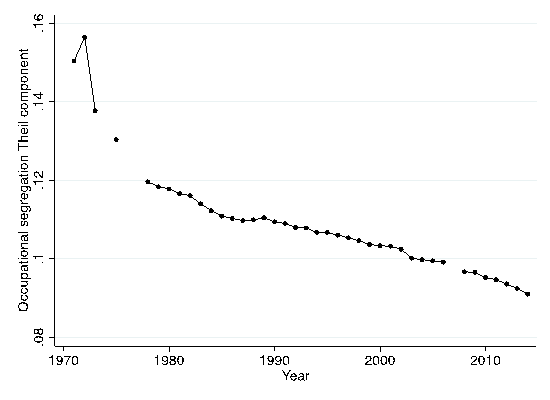

The United States struggles with a long history of racial employment segregation. Exclusionary hiring based on race was only banned in 1964; enforcement gained teeth after the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) set to work in the late 1960s and early 1970s. We know that segregation in employment declined significantly through the early 1980s. Since then, though, progress seems to have stalled. As Figure 1 illustrates, occupational segregation—how separated races are between different jobs—has barely moved in more than a generation.

Figure 1 – Racial segregation between US jobs has declined, at a declining rate

Yet even this is too rosy a picture. There are two broad ways to think about employment segregation. One is occupational, as already mentioned. The other is establishment segregation—how separated races are between different workplaces. (An establishment is an individual workplace; think a branch of Costa Coffee, not the entire corporation.) On this dimension, US workplaces have actually backslid to where they were in the mid-1970s, as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 2 – Racial segregation between US workplaces started climbing again more than 30 years ago

In a recent study, Rembrand Koning of Harvard Business School and I analyzed data on large US workplaces gathered by the EEOC. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires all firms with at least 100 employees to complete an annual survey that details counts of their employees by race and sex, across nine broad job categories, broken out by individual workplaces. Social scientists have long recognized these surveys as a rare and precious trove of information on employment composition. In particular, the EEOC’s surveys show workers clustered into workplaces, which almost never happens in US labor-market data. Yet almost no previous work had asked a seemingly simple question: how segregated were workers between different workplaces?

Photo by Daniel Bradley on Unsplash

We started calculating this, initially as background for another study. When we plotted the measure over time, though, we assumed we had messed up our code, because racial segregation in specific workplaces was trending upward. After a few days’ head-scratching, we concluded that we had working code, and a more basic question to answer.

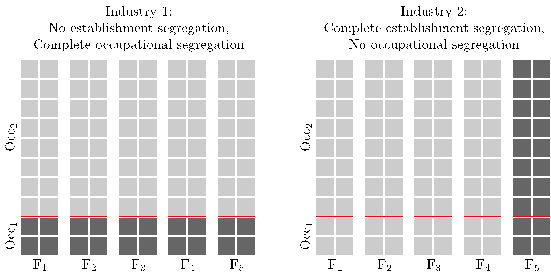

It is important to understand that occupational and establishment segregation reflect very different phenomena. We can imagine a society where one racial group monopolizes the prestigious, interesting, and well-paid jobs, while other groups are kept in token, subordinate, and unpleasant jobs. This would imply extreme occupational segregation; yet if such jobs were present in most all workplaces, there would be little establishment-level segregation. Conversely, in a perfectly “separate but equal” society all groups would be represented in all jobs, but those groups would work in parallel worlds. As Figure 3 shows, there would be no occupational segregation, but establishment segregation would be extreme.

Figure 3 – The difference between occupational and establishment segregation

The question then is not why researchers have looked at occupational segregation so often. The question rather is why establishment segregation has been comparatively ignored. Both of these are important!

We think there are two reasons. The first has to do with data. Most research on employment segregation relies on individual-level surveys, like the General Social Survey, the American Community Survey, or the Current Population Survey. You cannot gather good establishment-level information with such surveys—if you asked me to tell you what the racial composition of my employer’s workforce is, you would get an inaccurate answer. But you can ask me what I do for a living; and if your survey population is representative, then you can accurately estimate occupational segregation in the population at large.

There is nothing wrong with studying occupational segregation. Social scientists often have to restrict themselves to asking questions that their data can answer. The bigger surprise is that this was almost never acknowledged as a data limitation. Why?

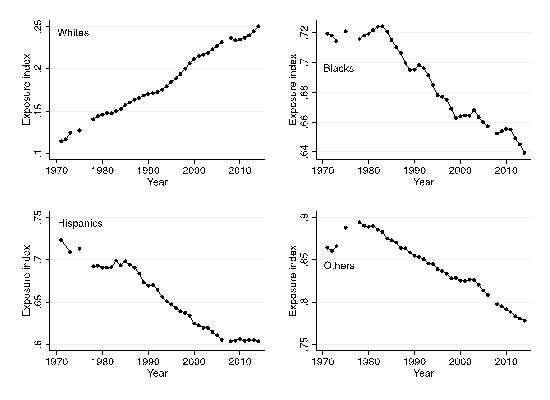

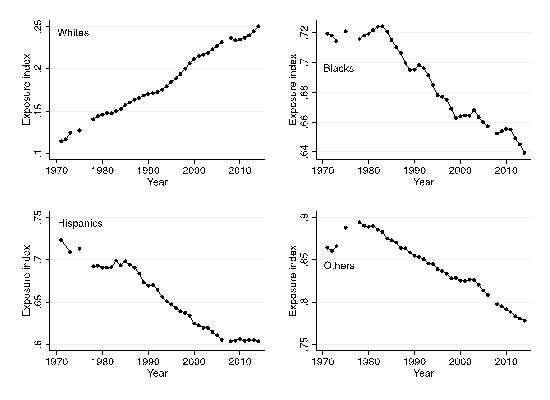

To answer this, it is worth talking about a different measure of segregation, what is called the exposure index. This is just the probability, for a worker of a given race that a randomly chosen co-worker will be of a different race. We calculated this as well, and found that exposure had consistently risen for white workers, while falling for every other group. (See Figure 4.) The most common US worker is white, and the typical white worker does work in a more diverse workplace than they did a generation ago. (This of course includes universities and other places that employ researchers.) Yet the larger workforce has diversified much faster than these workplaces have.

Figure 4 – White workers in the US are more exposed now to workers of other races in their workplaces. This does not hold for any other racial group.

It has therefore been easy for researchers (Including us—remember, we were not expecting to find this!) to look at our own workplaces, take it as given that there has been progress at the establishment level, and focus on whether that integration has been constrained by occupation. It has been easy, but wrong. The essence of segregation, after all, is that we cannot generalize from our local experiences. All in all, this should be sobering for social scientists. Not only have we made less progress as a society than we would like to think; we as a group know less than we assumed.

The outstanding question in the wake of this first study is why establishment-level segregation has been rising. We will be busy for several years trying to answer that—it is a truism that social problems are great news for researchers! We have a theory, though: we think that this rise is entwined with the wave of outsourcing and other corporate restructuring that began in the late 1980s. Restructuring often moved “non-essential” jobs in firms to external contractors. If much of the racial integration that did occur in establishments in the 1970s and 1980s involved hiring minority workers into lower-level, subordinate, “non-essential” jobs, then restructuring could tend to move them out of those workplaces and cluster them in specialized service providers. This process could easily produce increases in establishment segregation and decreases in occupational segregation simultaneously. In short, we habitually focus on the integration of workplaces, but may overlook what happens when we redraw the boundaries of those workplaces.

Getting hard data to nail down this idea is a capital-H Hard Problem, but those are what social scientists are supposed to work on. For example, we have a project underway to try to link the EEOC data discussed here to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational and Employment Statistics Survey. The promise of such work is that we could simultaneously examine the job composition within firms’ workplaces and the racial composition of their workforce across those workplaces. This could provide the smoking gun that, whatever employers’ intentions, a generation of outsourcing and restructuring has had a disparate racial impact. Which does not in and of itself mean that such practices are bad; we have developed standards for weighing such impacts in housing, schooling, and even voter registration, for example. But even partial judgments would be more thoughtful than today, when we rarely consider that the problem might exist.

- This article is based on the paper ‘Firm Turnover and the Return of Racial Establishment Segregation’ in the American Sociological Review

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2wbfAiO

About the author

John-Paul Ferguson – McGill University

John-Paul Ferguson – McGill University

John-Paul Ferguson is an Assistant Professor of Organizational Behavior at McGill University’s Desautels Faculty of Management. He studies careers, labor unions, and segregation.