Recent years have seen growing conflicts between groups over issues such as police brutality and immigration. In response to these conflicts, many cities have begun to use a human relations approach to bring people together through dialogue and an emphasis on group identity. Through new survey research, Valerie Martinez-Ebers, Brian Robert Calfano and Regina Branton look at the effectiveness of different types of messaging to improve relations between groups. They find that for Anglos, emphasizing a overarching group identity increased their perceptions of commonality with African-Americans, while Latinos felt more in common with Anglos.

Recent years have seen growing conflicts between groups over issues such as police brutality and immigration. In response to these conflicts, many cities have begun to use a human relations approach to bring people together through dialogue and an emphasis on group identity. Through new survey research, Valerie Martinez-Ebers, Brian Robert Calfano and Regina Branton look at the effectiveness of different types of messaging to improve relations between groups. They find that for Anglos, emphasizing a overarching group identity increased their perceptions of commonality with African-Americans, while Latinos felt more in common with Anglos.

With recent conflicts between groups in American cities over immigration, police brutality, and race-related issues, examining the effectiveness of local government strategies to resolve conflict and build positive relationships between racial and ethnic groups is imperative. In reaction to unrest, cities often increase policing and other enforcement activities to bolster public safety and penalize discriminatory practices. But another, arguably complementary, policy approach emphasizes “human relations” activities that focus on “bringing people together” through education, dialogue, and an emphasis on a wider, shared, group identity. In fact, local governments often pursue both general policies. In seeking to reduce group tensions, more than 500 US cities and counties have established human relations commissions (HRCs), many of which were constituted in the aftermath of racial uprisings or other conflicts between groups. Yet, there have been few assesments the effectiveness of a human relations approach for improving perceptions between diverse local groups.

We argue that HRC attempts at bringing people together overlaps with the mechanism that is inherent in how common group identity forms (“ingroup identity”). As such, in our research we test the likelihood of improving relations between groups via a common messaging intervention used by HRCs and similar organizations that emphasizes an overarching community identity among local residents of different racial/ethnic groups. As part of our study, we also examine the relationship of contact between groups with perceptions of commonality.We consider these messages and contact elements to be precursors to effective HRC efforts on the ground, thereby isolating their impact before scholars undertake a more comprehensive assessment of HRCs in the literature.

Social Identity Theory suggests people have a strong tendency to categorize and identify themselves and others in terms of their membership of a particular group. Self-categorization provides people with a sense of where they stand in relation to others, helping to determine appropriate attitudes and behavior. That said, individuals have multiple group identities, and research shows the importance of a particular identity can vary when people are encouraged to reflect on different identity conceptions of themselves and others. Our test case was Los Angeles-area residents, where both county and city-level human relations commissions regularly stage mediations designed to encourage improved relations between groups.

Photo by Toa Heftiba on Unsplash

We conducted an online survey experiment in 2015 involving over 900 Anglo and Latino Los Angeles County residents to see if an identity that encompasses different racial and ethnic groups could be encouraged through appeals to a common or overarching ingroup. Our main survey outcome question measured the commonality felt between groups: “Thinking about things like government services, political power, and representation, how much does your racial or ethnic group have in common with other groups in Los Angeles today?” Subjects answered the question for each group that did not reflect their self-reported race–ethnicity. Taking our cue from prior explanations of psychologist Gordon Allport’s (1954) theory as a proxy for intergroup contact, we also asked whether people had friends or coworkers who were of a different ethnicity to themselves.

Ahead of asking the outcome question, we split survey respondents into three groups. For the first group, we gave randomly assigned statements for subjects to read just prior to the outcome question of interest on the survey. A control group of subjects did not receive these random questions ahead of the outcome question being asked. For this first group, we emphasised an overarching or common group identity by distinguishing between the superiority of residents’ perceptions of community problems versus those of elected officials. The cue read: “Los Angeles area residents—no matter their race, ethnicity, or religion—may see community problems in ways that elected officials do not. This should be taken into account in any study of problems facing Los Angeles.”

For the second group, we emphasized subgroup distinctiveness in the perceptions of community problems. The statement cue for this group was: “Los Angeles area residents of certain racial, ethnic, or religious backgrounds may see community problems differently than others. This should be taken into account in any study of problems facing Los Angeles.” For a final, third group, we combined the prior two cue statements.

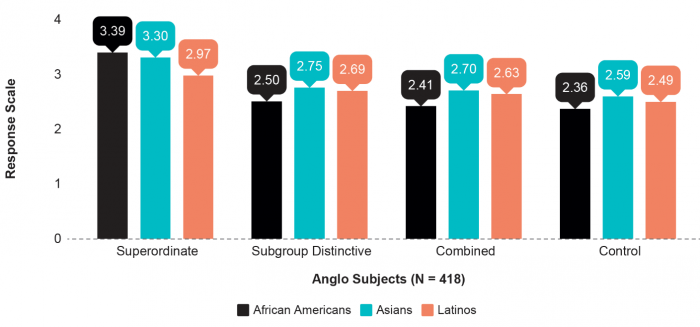

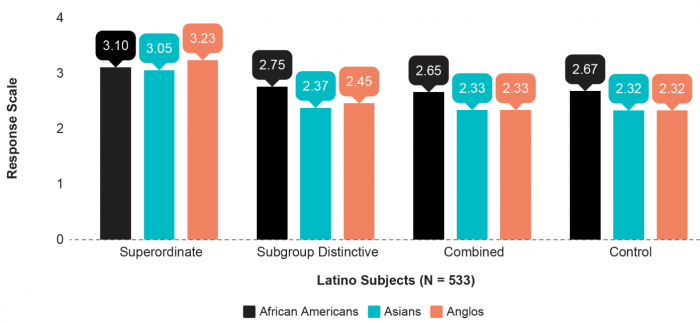

Our analysis of the differences between the cued and the control responses, shown in Figure 1 and 2, shows that among the first group, emphasizing common group identity increases Anglo’s perceived commonality with African-Africans by 1.03 points, Asians by .71 points, and Latinos by .48 points on the variable’s 1–4 scale. The effect pattern is similar among Latino subjects in Figure 2, where the common or overarching identity cue given to the first group increases perceived commonality with Anglos by .74, Asians by .73, and African-Americans by .43 points on the 1–4 scale (relative to the control).

Figure 1 – Mean comparison of political commonality with other groups (Anglos)

Figure 2 – Mean comparison of political commonality with other groups (Latinos)

Comparing the ability of the common identity cue to produce the intended outcome, we find Anglos moving toward greater perceptions of commonality with African-Americans over the other two groups and Latinos moving toward greater perceptions of commonality with Anglos. Interestingly, this observed difference between Anglos and Latinos is consistent with extant literature on race relations. We also found that common identity cue has a consistent effect even when controlling for economic and political variables such as party affiliation, education and income levels. Interestingly, however, reported contact between groups has no statistical effect on feelings of commonality between groups.

From a real-world perspective, these findings supplement the often-anecdotal assessments of successful intergroup relationship building from human relations commissions personnel in their local mediations between conflicting racial and ethnic groups. Human relations practitioners can leverage the evidence in our survey experiment to initiate or continue messaging strategies, with the caveat that racial/ethnic group perceptions, like messaging effects, may be short-lived. Policymakers will want to build on these findings, perhaps by encouraging an expansion of existing efforts to have members of different racial groups meet for mediated discussions over shared concerns across groups, as well as grievances relevant to particular minority groups.

- This article is based on the article “Bringing People Together: Improving Intergroup Relations via Group Identity Cues”, forthcoming in Urban Affairs Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2NvbZHI

About the authors

Valerie Martinez-Ebers – University of North Texas

Valerie Martinez-Ebers – University of North Texas

Valerie Martinez-Ebers is Director of Latina/o and Mexican-American Studies, and Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of North Texas. Dr. Martinez has published widely on education policy, Latino/a politics, women in politics, and methods of survey research.

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian Calfano is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and Journalism at the University of Cincinnati. He conducts research on marginalized groups, political information use, religion and politics, and journalistic coverage of political events. Brian has 40 peer-reviewed journal articles to his credit, and is the co-author of God Talk: Experimenting with the Religious Causes of Public Opinion (Temple University Press, 2013), and A Matter of Discretion: The Political Behavior of Catholic Priests in the U.S. and Ireland (Rowman and Littlefield, 2017).

Regina Branton – University of North Texas

Regina Branton is an associate professor of political science at the University of North Texas. Her research examines the behavioral, electoral, and institutional implications of race and ethnicity.