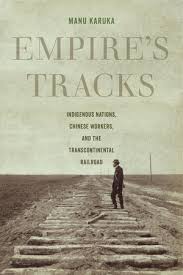

In Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers and the Transcontinental Railroad, Manu Karuka challenges longstanding myths surrounding the history of the US railroads, showing their construction to be dependent on gendered and racialised processes of conquest and exploitation. With the book adding to the growing literature that is reframing stories of expanding markets as critical narratives of imperial formations, Nicholas Barron welcomes its sincere meditation on the historicity of war, finance and countersovereignty that reveals the tragically unexceptional reality of the present.

Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers and the Transcontinental Railroad. Manu Karuka. University of California Press. 2019.

In the national imaginary of the United States, the joining of the Union and Central Pacific Railroads in 1869 is a vital anchor for the lore of free market vitality and patriotic exceptionalism. Manu Karuka’s Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad takes this historical moment as its jumping off point and, in a most interesting turn that foreshadows the book’s central claim, boldly reframes the joining of the railways as a ‘collective lie’ (xii). What follows is an ambitious, theory-driven re-examination of the presumptuous claims surrounding this history.

According to Karuka, the history of railroads in the US must be seen as a product of the interdigitation of capitalism, militarism and the state. These combined forces constitute a ‘war-finance nexus’ that has long undergirded what Karuka calls ‘countersovereignty’– the notion that settler invocations of an inherent right to land and governance are always already articulated in relation to a prior presence: namely, Indigenous peoples (2). Thus, railroads were far from the achievement of rugged individualists bravely navigating the contingent waters of the free market. As Karuka illustrates across nine arresting chapters, railroads were woefully dependent upon government and associated processes of gendered conquest and racialised exploitation that rendered Indigenous sovereignty null and void and imported Chinese labourers, a most exploitable tool of conquest. If not a lie, the national mythology is certainly a glaring misrepresentation – and one that Karuka is keen to clarify.

In the first three chapters, Karuka traces the contours of the theoretical field in which empire’s tracks have been laid down. Chapter One considers the methodological pitfalls of studying countersovereignty, which leaves behind a deeply compromised archival legacy that naturalises past acts of dispossession and exploitation. Karuka reconfigures the historical pursuit as one of ‘rumour control’, wherein the historian interrogates rather than ‘intones’ that which conquest leaves behind (19).

Chapter Two flips the coin to describe what countersovereignty operates against. Karuka joins the writings of three Indigenous intellectuals – Ella Deloria, Sarah Winnemucca and Winona LaDuke – to arrive at a theory of Indigenous ‘modes of relationship’. As described by Karuka, these modes are diametrically opposed to the intertwined forces of capitalism and colonialism. Where one is a matter of survival, the other is about conquest. Where one is about fostering relations (both local and international), the other is concerned with war-making and resource extraction (33). Chapter Three offers a panoramic and transnational view of ‘railroad colonialism’ to illustrate just how ‘unexceptional’ (40) the US and its railroad projects are when viewed through the prism of international networks of capital and empire. A reoccurring pattern of this history involves the willingness of imperial states to prop up private railroad projects amidst volatile global markets. In doing so, these polities subsidised the domestication and partition of space in a manner conducive to empire.

Image Credit: Railroad, Portland, Maine (Jack Flanagan CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: Railroad, Portland, Maine (Jack Flanagan CC BY 2.0)

The next four chapters rivet the book’s guiding concepts and themes to the US as Karuka hones in on the experiences of the groups caught in railroad colonialism’s race across the North American continent. This section highlights Indigenous encounters with the war-finance nexus told through the cases of the Lakota, Pawnee and Cheyenne. Recurrent themes include the negotiation of treaties under duress, the violation of said treaties in relation to the needs of railroads and corresponding market forces and the usurpation of women’s authority within Native communities as a tactic of conquest.

With the examination of Chinese labour in California in Chapter Five comes an exploration of the multifarious tools of railroad colonialism. Karuka defines the Chinese position in the war-finance nexus as being an expendable tool of territorial incorporation and domestication. Not quite enslaved, but certainly not free, Chinese workers were positioned as a cheap and reliable means of manifesting Anglo-American destiny or, as Karuka acutely puts it, they were ‘the constant capital of a colonial mode of relationship’ (100).

The remaining chapters pull back from these more specific cases to discuss the codification of railroad corporate personhood as an investment in whiteness and continental imperialism predicated on the perpetual deferral of racial and territorial equity. Once again, Karuka recasts the US not as a nation premised on free market values and anti-colonial revolution (as it so gregariously tells itself every fourth of July), but as an empire dependent upon monopolistic trusts, racialisation and countersovereign acts of aggression.

With this history of railroad colonialism in full view, the epilogue turns to the ‘significance of decolonization’ in and beyond North America. Karuka characterises US military, energy and financial policy associated with the ‘War on Terror’ as the continued imperialisation of US countersovereignty. As he so succinctly puts it: ‘Imperial sovereignty involves the transformation of the entire world into Indian country, where the hand of the market is backed by the fist of military power’ (195). But all is not doom and gloom for, as Karuka observes, US empire is a ‘chain built of weak links’ (185). Attempts to reinstitute modes of relationship across Native and non-Native communities offers a sign of contemporary anti-imperialist struggle capable of breaking the links on the chain.

The strengths of Empire’s Tracks flow from Karuka’s intricate theoretical apparatus. The use of ‘countersovereignty’ effectively denaturalises and historicises that which we take for granted –the legitimacy of settler colonial societies. Not only does the concept highlight the injustice done to Native communities (the usurpation of their right to land and self-governance), but it more ably helps us understand settler sovereignty for what it is – the product of complex and contingent negotiations of labour, capital, military and government.

Almost inevitably, the pursuit of a complex, comparative narrative is likely to leave specialists wanting more. For example, references to the social, economic and political reconfiguration of Lakota groups prior to the advent of the railroads are noticeably brief and say little of the rise of the Lakota as a political and economic force on the plains during the late eighteenth century and subsequent intertribal conflicts. However, this should in no way lead one to assume that Karuka has glossed over the ways in which Indigenous communities came to move with the rhythms of imperialism and global markets. The emphasis on Indigenous women is particularly instructive as we learn time and again how the war-finance nexus undermined pre-existing social and economic systems rooted in relationships with women and how Native groups creatively devised ways of renewing and reinforcing these relationships in a shifting world. The efforts of Pawnee women to continue to cultivate their own gardens and maintain caches of resources shared within the village amidst the construction of federally-managed agricultural districts and gendered, religious-vocational schooling (105-112) is a particularly striking example of how Indigenous peoples responded to their immersion in settler-dominated economies and social paradigms.

With Empire’s Tracks, Karuka joins a cohort of scholars based in American Studies and Indigenous Studies reframing stories of expanding markets as critical narratives of imperial formations. Due to its deep engagement with a diverse assortment of critical theory, the book will be ideal for graduate seminars across the humanities and social sciences. Moreover, Empire’s Tracks comes at a critical juncture, which only compounds its appeal. It is a moment where monopolies breathe new life as seemingly benevolent multinational, e-commerce corporations; when oil pipelines continue to cut through North America despite opposition from Indigenous peoples (amongst others); and when threats of mass deportations emanate from the highest political offices. In this context, Karuka’s sincere meditation on the historicity of war, finance and countersovereignty is deeply welcomed as it sensitises readers to the tragically unexceptional reality of the present.

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2Yx32i9

About the reviewer

Nicholas Barron – University of New Mexico

Nicholas Barron is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico. His research interests include the history and sociology of science, historical anthropology and imperial/colonial studies. Funded by the University of New Mexico and Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, his doctoral research explores the co-production of anthropology and Indigenous politics in the US Southwest. Nicholas also serves as an editor for the History of Anthropology Newsletter.

Find this book:

Find this book: