In elections, those already in office – incumbents – tend to have a considerable advantage over a challenger. But how is this advantage shaped by how incumbents and their challengers campaign? In new research, James N. Druckman, Martin J. Kifer and Michael Parkin coded the content of US House and Senate candidates’ websites and find that while incumbents tend to emphasize their close links to their districts, challengers tend to be more negative and are more likely to discuss the issues. Following up this analysis with an experiment, they determine that when incumbents do not emphasize these close links, voters interpret the election as being more competitive and are more likely to consider a wider set of issues. If they want to win re-election, incumbent candidates are actually better off doing very little in their campaigns.

In elections, those already in office – incumbents – tend to have a considerable advantage over a challenger. But how is this advantage shaped by how incumbents and their challengers campaign? In new research, James N. Druckman, Martin J. Kifer and Michael Parkin coded the content of US House and Senate candidates’ websites and find that while incumbents tend to emphasize their close links to their districts, challengers tend to be more negative and are more likely to discuss the issues. Following up this analysis with an experiment, they determine that when incumbents do not emphasize these close links, voters interpret the election as being more competitive and are more likely to consider a wider set of issues. If they want to win re-election, incumbent candidates are actually better off doing very little in their campaigns.

Incumbents enjoy a well-known advantage in US Congressional elections. Numerous studies show that incumbents receive an electoral edge of between 2 percent and 12 percent simply by holding office already. Scholars have identified an array of factors that contribute to the incumbency advantage, including strategic retirements, spending advantages, redistricting, television coverage, etc. Surprisingly, though, few have considered how the electoral campaign itself might shape the incumbent’s advantage. How do incumbents and challengers campaign and how do the campaigns affect voters?

In new research, we use a large-scale content analysis of congressional campaign websites and an experiment to explore these questions. We first focus on candidate rhetoric by coding the content of a random sample of US House and Senate candidate websites. The sample includes 369 websites from the 2010 election. We sought to identify candidate negativity and the ways in which candidates talked about issues (e.g., did they take clear positions? did they focus on issues often connected to their party?) and image (e.g., did they focus on leadership, empathy?). We also analyzed whether candidates used “homestyle” rhetoric — that is, a focus on being experienced, familiar with the district, and took actions that benefitted the district. We suspect that these latter attributes advantage the incumbent since he/she by definition is experienced, knows the district, and has had the opportunity to act on its behalf.

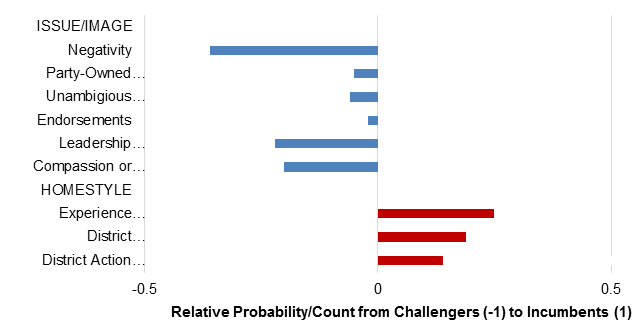

Our content analysis shows that incumbents use decidedly different rhetoric than challengers. As shown in Figure 1, challengers consistently engage in more negativity and accentuate issues and image. In contrast, incumbents outpace challengers in their discussion of homestyle features. Why is this? We argue it reflects incumbents playing it safe by sticking to their strengths. Challengers, however, seek to gain voter attention by going negative — which is a well-known tactic to stimulate attention — and highlight issues and image in an attempt to stir debate. Put another way, challengers want voters to engage and consider the issues and personality features of the candidates; these are the criteria on which challengers at least have a fighting chance. If homestyle factors dominate, incumbents nearly always will carry the day. This latter point is why incumbents do little more than remind voters that they are incumbents.

Figure 1 – Candidate Rhetoric

We then conducted a laboratory experiment, using mock-versions of candidates’ websites, to see how differing rhetorical strategies affect voters’ decisions. We based the experiment on the 2010 House election in Illinois’ 9thdistrict that pitted incumbent Democrat Jan Schakowsky against Republican challenger Joel Pollak. The district mirrors the partisan lopsidedness of many US House districts, yet 2010 was the first year in at least a decade that there was a bona fide challenger for the seat.

“RushHoltYardSign2008” by Wasted Time R is licensed under CC BY 3.0

We ran the experiment from June to August 2010, which encapsulated the start of the campaign but was prior to major campaign activity. We created Schakowsky and Pollak campaign websites that drew content from the candidates’ own sites, speeches, news coverage and, for Schakowsky, floor votes. One version of each candidate’s website emphasized issue and image considerations whereas the other version promoted a homestyle strategy in which the candidate focused on experience, familiarity and actions for the district. We then recruited 395 participants who lived (and were able to vote) in the district. The participants first read a brief overview and then were randomly assigned to one of five conditions. The control condition had participants browse non-campaign websites before answering a survey about the candidates. The other conditions presented participants, prior to the survey, with Schakowsky and Pollak websites that each used either the issue/image strategy or the homestyle strategy. All together this led to four mixes: both sites using issue/image, Schakowsky issue/image against the Pollak homestyle, Schakowsky homestyle against the Pollak issue/image, or both homestyle.

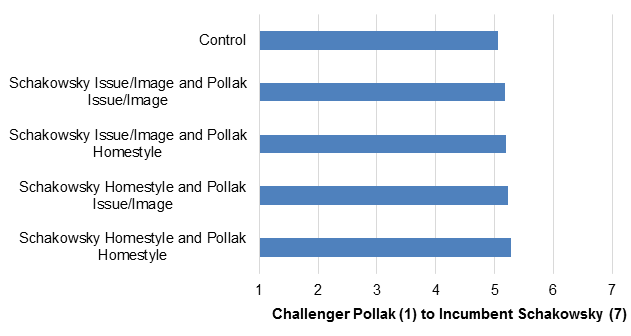

The experiment produced a set of interesting results. To begin with, as anticipated, the incumbent (Schakowsky) was inherently favored—regardless of the sites viewed—on perceptions of experience, familiarity, and actions for the district. Figure 2 shows that, in every scenario, voters rated her higher than Pollak on these dimensions. Even when the challenger highlighted his experience, familiarity, and district actions (using the homestyle strategy), it did not dislodge the inherent preference for the incumbent Schakowsky on these criteria. There is almost nothing a challenger can do to gain an edge on these dimensions in voters’ minds. This confirms that incumbents do in fact have an inherent advantage.

Figure 2 – Perceptions of Candidate Experience, Familiarity and Actions for the District

Interestingly, the experiment also showed that voters perceived the election to be more competitive when the incumbent Schakowsky employed an issue/image strategy rather than a homestyle strategy (see Figure 3). Talking about issues and image (rather than experience, familiarity and actions for the district) signals to voters that the race may be close. This suggests that the only scenario in which voters might perceive a competitive election and thus feel a need to reconsider their vote choice is when an incumbent emphasizes dimensions on which they are not inherently favored (i.e., recall that the incumbent Schakwosky was always favored on homestyle criteria). What is going on here is that voters recognize an incumbent who engages in unexpected ways and read it as a signal that the incumbent may be nervous because of competition.

Figure 3 – Perceptions of Election Closeness

Finally, our experiment revealed that differing rhetorical strategies influenced the way voters formed their preferences. The results of a regression analysis show that participants put weight on issue and image considerations in their vote choices when the incumbent emphasized those considerations. They did this while also downplaying homestyle criteria. In contrast, when the challenger focused on issues and image, which is typical, it had no significant effect on how voters made their choices. It is the incumbent, not the challenger, who can move voters from relying on homestyle considerations that favor the incumbent. The implication is that incumbents are typically better off sticking to the homestyle strategy, focusing on their close links to the district. When they fail to do so, they signal competitiveness and voters start to consider criteria that do not always favor the incumbent. This explains our content analysis results that incumbents tend to employ the homestyle approach since failing to do so could cost them.

In sum, voters rely on easily accessible and well-known incumbency factors unless there is a signal to pay attention and process new trait and policy information. That signal, at least when it comes to campaign rhetoric, is contingent on the behavior of the incumbent using a strategy that is not in his or her interest to use. The campaign is a mechanism through which the incumbency advantage works. The factors that bias voters toward the incumbent incentivize the incumbent to focus on those criteria, and that, in turn, ensures the incumbency advantage. The challenger is in an unenviable situation, given his or her campaign strategy cannot, on its own, induce voters to consider the criteria that could, in theory, advantage him or her. The challenger must then hope for an incumbent campaign to make a mistake or for some other outside factor that somehow triggers perceptions of competition (e.g., intense media scrutiny).

These results raise some important concerns about our politics. It is certainly reasonable to expect that voters will choose high-quality candidates and that incumbents will win reelection in districts with favorable partisan constituencies. It is not surprising that districts with higher proportions of Democrats or Republicans are more likely to elect representatives from the dominant party. The problem we identify for democratic theory is that in addition to the composition of the district and various other advantages incumbents enjoy, incumbent rhetorical styles can further exacerbate those inherent advantages. The safe rhetorical strategy commonly used by incumbents results in an easy reelection in most cases. The key is that voters reward incumbents for doing next to nothing in the campaign, whereas challengers are punished (or at least not rewarded) for trying to start the kind of substantive debate that should be the center of all elections.

Districts should get the representatives they want but, ideally, the election outcome should be the result of a vigorous exchange of ideas which leads voters to seriously consider their choices. There is nothing wrong with high-quality incumbents winning reelection, but there is something unsettling about their ability to win reelection by doing little more than reminding voters that they are incumbents.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Campaign Rhetoric and the Incumbency Advantage’, in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2GTay04

About the authors

James N. Druckman – Northwestern University

James N. Druckman – Northwestern University

James N. Druckman is the Payson S. Wild professor of Political Science and a faculty fellow at the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University. He studies political communication and preference formation and is the co-principal investigator of Time-Sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences. More information can be found at: http://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/~jnd260/.

Martin J. Kifer – High Point University

Martin J. Kifer – High Point University

Martin J. Kifer is chair and associate professor of Political Science at High Point University and director of its Survey Research Center (SRC). His research and teaching interests include political campaigns and new media, survey research methods, public opinion, and US foreign policy. The SRC’s HPU Poll conducts periodic election year surveys analyzing national and state campaigns, often focusing on the North Carolina electorate.

Michael Parkin – Oberlin College

Michael Parkin – Oberlin College

Michael Parkin is the Erwin N. Griswold professor of Politics at Oberlin College. He is also the Director of the Oberlin Initiative in Electoral Politics. His research and teaching interests are in campaign communication with a particular focus on candidate use of new media. He is the author of Talk Show Campaigns: Presidential Candidates on Daytime and Late Night Television.