Many Americans are represented in Congress by someone who does not share their party affiliation – who do they look to for political representation? In new research using a national-level study, Ashley English, Kathryn Pearson, and Dara Strolovitch find that most Americans do not feel best represented by their member of Congress, and that sharing partisanship – or being of the same race – with their member of Congress makes it more likely that they will feel that they are best represented by them.

Many Americans are represented in Congress by someone who does not share their party affiliation – who do they look to for political representation? In new research using a national-level study, Ashley English, Kathryn Pearson, and Dara Strolovitch find that most Americans do not feel best represented by their member of Congress, and that sharing partisanship – or being of the same race – with their member of Congress makes it more likely that they will feel that they are best represented by them.

With congressional approval rates for the current (116th) Congress hovering around 19 percent, it is no secret that many Americans disapprove of the legislative branch, even as more than 90 percent of incumbents are typically reelected. But it is surprising that until recently, we knew very little about to whom Americans look when they don’t feel represented by their own representatives in the House, perhaps because of their partisan, racial, or gender identity.

Who Should Represent Me?

The disconnect between the American people and their members of Congress (MCs) would likely be surprising to the Framers of the United States Constitution, who expected that MCs serving in the House of Representatives would be closely connected to their constituents. In Federalist 52, Madison stated, “As it is essential to liberty that government should have a common interest in the people, so it is particularly essential that the branch under consideration [The House of Representatives] should have an immediate dependence on, and an intimate sympathy with, the people.” The Framers structured the House so that it would be composed of MCs directly elected by their constituents in small districts every two years, and they hoped that this proximity would ensure that House members would most effectively represent the American people.

Representation requires more than geographic connections and regular elections, however. Instead, connections between MCs and their constituents are most easily forged when they share social perspectives and experiences because of their partisan, racial, or gender identifications. Unfortunately, for many Americans, those shared perspectives and experiences may be hard to find. In the current polarized political environment, voters increasingly disapprove of the rival political party, but have few opportunities to vote out incumbents who do not share their partisan identifications because most House seats are safe for one of the two parties. Women and people of color also remain dramatically underrepresented in the House. Even after voters elected the most diverse Congress ever in terms of gender, race, and ethnicity in 2018, women and people of color still held only 24.3 percent and 27.8 percent of the seats in the House, respectively. Together, partisan divides and lack of descriptive representation help explain why some Americans may reject the representation that their members of the House provide. But who do they turn to and what do they do if they reject their House members?

Who else could represent me?

Americans are not only represented by their members in the House, they are also formally represented by the two Senators from their state and the President of the United States. Informally, they can also seek out a wide range of individuals and organizations both inside and outside of government. For example, those represented by a member of Congress of the other party could turn to their own party’s leaders instead. Women and people of color who are represented by MCs who do not share their gender or racial identities could instead seek out members of an identity-based congressional caucuses (the Congressional Black Caucus, the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus, or the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues) that explicitly formed to act on behalf of women or people of color. Likewise, people could look beyond government institutions and political parties altogether by turning to interest groups or advocacy organizations that exist to fill in some of the gaps in electorally-based representation for members of underrepresented marginalized groups.

How we examined representation

Building on these insights, we included an original question on the 2006 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) to determine which of the political actors described above that people believe effectively represent them at the national level. It asked: “Which of the representatives listed above do you look to MOST to represent you in Washington?” and respondents were presented with a list of options that included: “the House member from your district;” President George W. Bush; Republican congressional leaders such as Dennis Hastert, Democratic congressional leaders such as the then House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, the Congressional Black Caucus, the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus, the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues, and organizations that speak for different groups or about different issues. Thus, unlike many existing studies, we examined representation by asking a fundamental question about who people feel or believe represents them, rather than approaching representation using questions about political trust, alienation, approval, and/or alignment between constituents’ policy preferences and legislative outcomes.

Credit: United States House of Representatives or Office of the Speaker of the House [Public domain]

Next, we used the responses to that question as well as CCES data about the respondents’ party identification, race, gender, political knowledge, education and income, and combined with publicly available data on the MCs’ party, seniority, party leadership positions, committee chair positions, campaign spending, race, and gender to test two for two possibilities.

The first is that those who are represented by a member of Congress who share their party identification – so someone who identifies as a Republican living in a Republican-represented district, for example – are more likely to say that that they look to their own member for representation in Washington, compared to those in the same district who identify with a different party.

The second possibility is that constituents who share a racial or gender identity with their own members are more likely than constituents who do not share a racial identity with their members to turn to their own members for representation in DC.

So who does represent me?

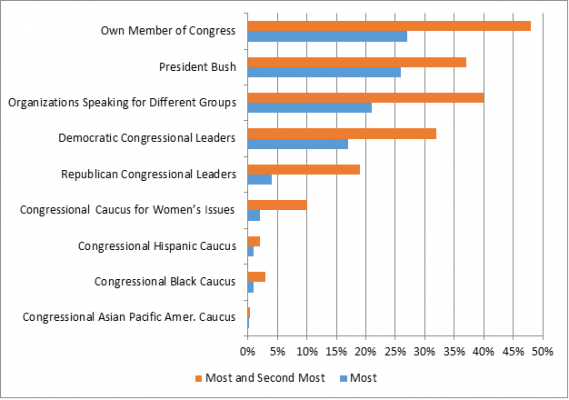

Our analyses revealed three central themes. First, most Americans do not necessarily believe that their MCs represent them the best. As Figure 1 shows, when respondents were asked to select one political actor who represented them “the most,” a plurality, but far from a majority, chose their own member of Congress (27 percent). Even when we included the actors that respondents felt represented them “the second most,” less than half (48 percent) of respondents chose their own House members.

Figure 1 – Who do respondents look to for representation in Washington DC?

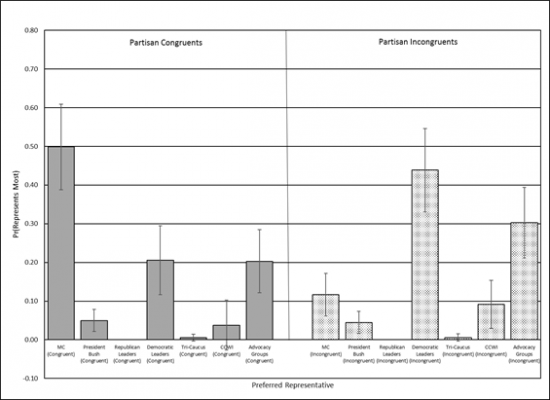

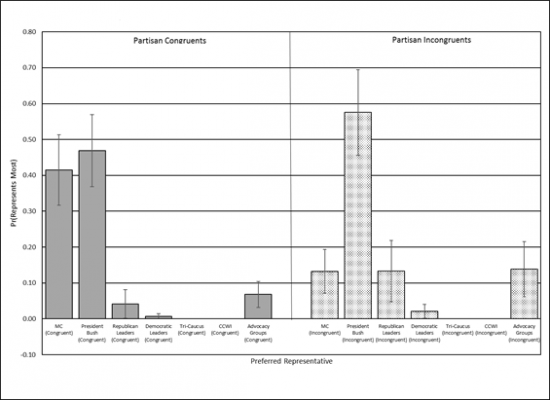

Second, partisanship informs Americans’ views on representation. People who shared a partisan affiliation with their House members were significantly more likely than those who did not to look to them for representation. For example, 41.8 percent of those who shared the same party identification as their member of Congress indicated that they looked to their own member the most. In contrast, only 15.5 percent of those who did not share the same party identification selected their own House members. When we conducted multivariate analyses to determine which political actors people selected, we found that 50 percent of Democratic and 41 percent of Republicans who had the same party affiliation as their member felt they represented them the most (Figures 2 and 3). Identifying with the same party increased the chances that respondents reported their own members represented them the best by 38 percent for Democrats and 28 percent for Republicans.

Figure 2 – Democrats’ preferred representatives by partisan identification (congruence)

Figure 3 – Republicans’ preferred representatives by partisan identification (congruence)

Our results also provide some insights into who those who are not represented in Congress by someone from their preferred party turn to for representation. We found that Democrats preferred Democratic Party leaders and advocacy organizations to their own MCs (Figure 2). Republicans in the same position, meanwhile, selected (then) President Bush and Republican congressional leaders over their own MCs.

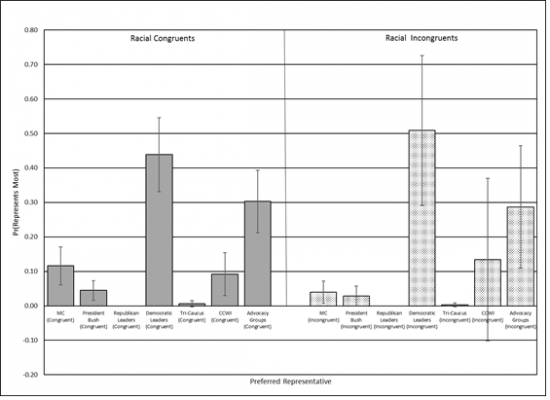

Third, people are more likely to feel connected to their House members when they are represented by an MC of the same race. Twenty-nine percent of those who were represented by someone of the same race (e.g. African American constituents represented by African American MCs, whites represented by white members of Congress (MCs), Latinx constituents represented by Latinx MCs, and Native Americans represented by Native American MCs) reported that their they represented them the most, compared with only 23 percent of those who were not represented by someone of the same race. Thus, being represented by someone of the same race increased the chances that respondents felt their own MCs represented them the best by 6 percent. Our analyses shown in Figure 4 also indicate that there was a 12 percent chance that those of the same race reported their own MCs represented them the best, compared with a 4 percent chance for those who were of a different race. In other words, being of the same race increased the chances that respondents would turn to their own MCs for representation by 8 percentage points.

Figure 4 – Respondents’ preferred representatives by racial congruence

Citizens are not all that close to their members of Congress

Altogether, our results indicate that the representational connection between constituents and their House members is far more tenuous than the Framers intended it to be. A majority of Americans look to other political actors for representation in Washington, DC. Those who do look to their own members of Congress are much more likely to share the same party label. Given the partisan politics in the United States today, it is difficult for members of Congress to bridge the divide between themselves and their constituents from the opposing party. For many, advocacy organizations and party leaders provide an important form of representation for Americans who do not feel their members represent them. Our results also suggest that descriptive representation matters, as both people of color and whites value being represented by members of Congress who “look like” them.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Who Represents Me? Race, Gender, Partisan Congruence, and Representational Alternatives in a Polarized America’in Political Research Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ZeLAii

Ashley English – University of North Texas

Ashley English – University of North Texas

Ashley English is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of North Texas. Her research focuses on gender and politics, interest groups and women’s organizations, and representation in the policymaking process.

Kathryn Pearson – University of Minnesota

Kathryn Pearson is an Associate Professor specializing in American politics; her research focuses on the United States Congress, congressional elections, political parties, and women and politics.

Dara Strolovitch – Princeton University

Dara Strolovitch – Princeton University

Dara Z. Strolovitch is Professor at Princeton University, where she holds appointments in Gender and Sexuality Studies, African American Studies, and the Department of Politics.