Are women really at a disadvantage compared to men when they run for elected office? In new research, Rebecca D. Gill and Kate Eugenis look at how women fare when they run for state supreme court judgeships. Using over 15 years’ worth of election data across the states, they find that women are seven percentage points more likely than men to win elections against incumbents, and that they do no better or worse than men when they are incumbents themselves or run in open seat races.

Are women really at a disadvantage compared to men when they run for elected office? In new research, Rebecca D. Gill and Kate Eugenis look at how women fare when they run for state supreme court judgeships. Using over 15 years’ worth of election data across the states, they find that women are seven percentage points more likely than men to win elections against incumbents, and that they do no better or worse than men when they are incumbents themselves or run in open seat races.

People commonly believe that women have a disadvantage when they run for elected office. However, women were overwhelmingly successful running for and obtaining election to public office in the 2018 US midterm elections. This pattern also held in races for state supreme court judgeships, where women also did considerably well. We decided to investigate whether this electoral disadvantage really exists, or if it has been a myth all along. To do this, we looked at elections for supreme court judgeships in the American states from 1998-2014. We find evidence that women actually enjoy a slight advantage when running for state supreme court. That advantage, however, is limited to women running as challengers against incumbent judges. In all, this means that this slight advantage is unlikely to increase the proportion of women on state supreme courts. However, we find no evidence of a systematic disadvantage for women candidates, provided that they make it through the primary election process and onto the general election ballot.

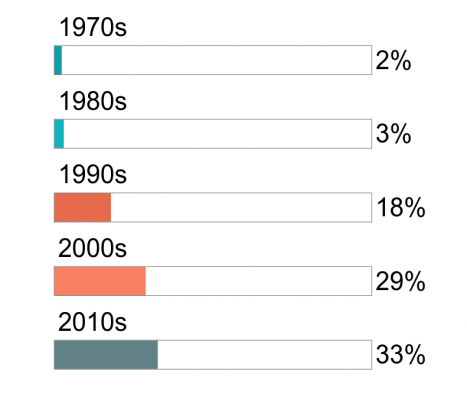

Women have been underrepresented in the judiciary for most of American history, but this seems to be changing. In 2018, women held the majority of seats in just 11 state supreme courts; Iowa had no women on its supreme court that year. This is a big improvement from just a few decades ago. Currently, roughly 35 percent of state supreme court seats are held by women, up from an average of 3 percent in the 80s.

Figure 1 – Women as a Percentage of State Supreme Court Justices by Decade

The rising numbers of women on the bench could be a result of a couple of different things. First, more women have been attending law school over the last few decades, and women have recently overtaken men as law school graduates. This means that the pool of judicial candidates has more women in it. But this probably does not explain the increase, since women still have a hard time advancing in their legal careers.

The increase could also be a result of changes in people’s perception of what a judge looks like. Some of this could be driven by many years of popular television programming featuring women as judges. For instance, Judith Sheindlin (Judge Judy) has been on air since 1996, and Divorce Court has featured women as judges for a majority of the past 30 years. These portrayals might help voters get used to the idea of women as judges, and might make them more willing to vote for women candidates.

“Supreme Court of Nevada, Carson City, Nevada” by Ken Lund is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

To get a handle on our research question, we looked at the percentage of the vote each candidate won in state supreme court elections. We modeled this as a function of their gender, incumbency status, and several additional factors. When we looked at these data, we found many interesting trends and some unexpected ones, too. For example, contrary to research on congressional elections, we found evidence that women do not face stiffer competition when they run for reelection to the state supreme court. Incumbent women are not challenged more often than incumbent men.

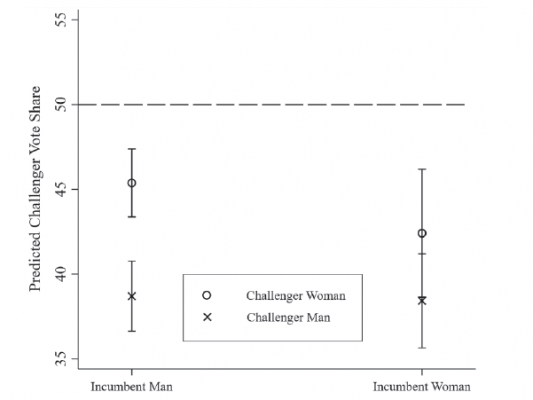

We also found evidence that women do better than men in certain circumstances. When they are challenging incumbents, women enjoy a nearly seven point vote share advantage over similar men who challenge incumbents. However, women incumbents do not enjoy this advantage. This means that women who run as challengers are also advantaged when they run against women who are incumbents as seen below.

Figure 2 – Estimated Vote Share for Challengers by Gender Configuration

At first, this looks like good news for people who would like to see women represented equally on state supreme courts. However, our findings are also consistent with a longstanding thread of literature on elections: incumbents have an overwhelming advantage when they run for reelection. Therefore, while women may have a slight advantage when they run as challengers compared to a similar man who runs as a challenger, this advantage is not very helpful if it does not result in the women challenger beating the incumbent man. For instance, we find that a woman would obtain 46 percent of the vote against an incumbent when a man would have only obtained 39 percent. However, 46 percent of the vote is still not enough to unseat the incumbent, so the result is the same.

But there is some cause for optimism. First, there are some situations where the additional votes can make a difference in the outcome of the election. Of the 143 races in our sample where incumbents were challenged, the incumbent won in 86 percent of those contests. When the challenger was a woman, that win rate dropped to 76 percent. This suggests that women can translate that advantage into electoral victories.

Secondly, it does not appear that women are particularly disadvantaged in state supreme court elections. Our findings indicate that women who run as incumbents or in open seat elections do no better and no worse than similar men. Of course, there might be other ways that women are disadvantaged that we cannot determine from our analysis. For example, women may be disadvantaged in other ways earlier in the electoral process, like in the primary election.

Perhaps the most interesting part of our findings is the advantage we find for women running against incumbents. This goes against most of what we know about how elections usually work. Trying to explain why women do better against incumbents is difficult. We think it might have something to do with the ability of women to enter the race strategically. In other words, challenger women may have an advantage because they have the opportunity to choose which incumbent to target. Incumbents do not have this option, as they must run when their term expires (or they can retire). Likewise, potential candidates are unable to choose their challengers in open seat elections, as the list of candidates is not solidified until the filing date. The fact that we only see this electoral advantage for women as challengers suggests that women may benefit from their more strategic decision to enter the electoral arena.

Ultimately, an electoral advantage accrues to women only when they challenge incumbents. However, our results identify no systematic gender-based electoral disadvantage in any of these state supreme court races. Gender diversification of the bench is taking place at what seems like a glacial pace, which leads many to assume that voters are unfriendly to women as candidates. Our research suggests voters do not punish women running for judicial office. In fact, they may see challenger women as particularly strong candidates. Understanding the role of challenger women, particularly as it relates to dismantling assumptions about gender stereotypes and the incumbent advantage, is timely and worthy of further study.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Do Voters Prefer Women Judges? Deconstructing the Competitive Advantage in State Supreme Court Elections’, in State Politics & Policy Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2Ns62dj

About the authors

Kate Eugenis – University of Nevada Las Vegas

Kate Eugenis – University of Nevada Las Vegas

Kate Eugenis is an affiliated researcher with the Women’s Research Institute of Nevada at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. Her research focuses on elections and candidate emergence.

Rebecca Gill – University of Nevada Las Vegas

Rebecca Gill – University of Nevada Las Vegas

Rebecca Gill is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. Her recent work focuses on gender, politics, and legal systems. She is also active in efforts to promote equity in higher education by improving the workplace climate in academic departments.