Work-related training and qualifications are very important in today’s knowledge-intensive economy. Public workforce programs help to connect workers to jobs via helping with job searches, and through training schemes. As funding cuts shift the bill for these programs to state and local governments Elsie Harper-Anderson looks at the return for investing in job seekers’ training. Focusing on workforce programs in Virginia, she finds for every dollar spent on providing training through one program, the authority received nearly $4 back through reduced welfare costs and increased tax returns, with the figure topping $5 when participants gained a qualification.

Work-related training and qualifications are very important in today’s knowledge-intensive economy. Public workforce programs help to connect workers to jobs via helping with job searches, and through training schemes. As funding cuts shift the bill for these programs to state and local governments Elsie Harper-Anderson looks at the return for investing in job seekers’ training. Focusing on workforce programs in Virginia, she finds for every dollar spent on providing training through one program, the authority received nearly $4 back through reduced welfare costs and increased tax returns, with the figure topping $5 when participants gained a qualification.

By 2020, 65 percent of all jobs will require some form of training or credential beyond high school. Many workers facing barriers to employment are finding it increasingly difficult to participate and prosper in the current knowledge-intensive economy due to having inadequate skills. There is an ongoing debate among scholars and policymakers over how many taxpayer dollars should be spent on public workforce programs which are charged with connecting workers to jobs and whether there is a return for this investment.

The purpose of the public workforce system is to connect people to work either through helping them in their job search or through training that makes them more employable. The public workforce system has received a fair share of criticism over its many programs and whether they are effective or not. Questions have also been raised over duplication and overall priorities. The cost of training is the most contentious issue as training is by far the greatest program expense.

While proponents of the “work-first” approach advocate for shorter-term training programs that put job seekers into the first job available, these jobs are often less than optimal in terms of pay, number of hours and working conditions. On the opposing side of the debate are advocates of longer-term training which lead to a credential or qualification. Credentials allow workers to qualify for higher-paying, more stable jobs enabling greater self-sufficiency. However, longer-term training is also more expensive and delays a worker’s entry into the job market.

At the beginning of his presidency, Donald Trump proposed cutting the US Department of Labor’s budget by as much as 40 percent with a great proportion of the cuts targeted at training. Funding cuts at the Federal level over the last few decades have shifted a greater amount of the responsibility to pay for workforce services to state and local governments. Policymakers charged with making decisions about where to spend their constituents’ tax dollars want to know whether there is a return for investing in training job seekers.

Workforce Investment Act programs

Today the Federal workforce system is made up of a myriad of programs each serving a unique client base and offering its own slate of services. The programs date back to Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty in the 1960s and have continuously evolved in response to economic and political changes over the years. Federal programs are implemented through state and local workforce boards. The Commonwealth of Virginia hosts 28 different public workforce programs including Workforce Investment Act programs (WIA) and the Trade Adjustment Assistance program (TAA).

Derived from the Workforce Investment act of 1998, WIA assists adults, dislocated workers and youth workers. Many of its participants have significant barriers to employment. In Virginia WIA participants tend to be younger, have low education levels, are disproportionately African American (45 percent), majority women (58 percent) and most are unemployed prior to enrolling in the program. The Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program assists workers who have been impacted by foreign trade. In 2012 the program assisted 81,500 workers across many industries but manufacturing represented the majority (65 percent). TAA participants in Virginia tend to be older, white (69 percent), men (59 percent) who were employed prior to program participation.

“Road work ahead” by Martin Kenny is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0

In a recent study, I estimated return-on-investment (ROI) for money spent on WIA and TAA programs in Virginia and examined what factors influenced employment and earnings outcomes once participants exited the program. The analysis took into consideration costs and benefits. Costs consisted of administrative program costs and training costs. Benefits consisted of savings from workers leaving public assistance programs once they gained employment and additional taxes paid on any increased earnings. I disaggregated the results to compare the ROIs for participants who received training without earning a credential to those of participants whose training led to a credential. For each program, I use administrative program data from 2008 to 2012. Each record also included earnings data from the Virginia Employment Commission.

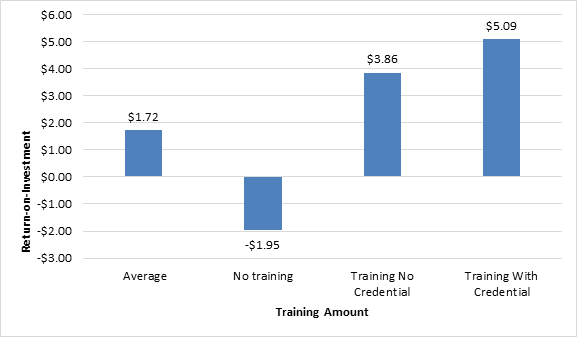

I find that there is a positive ROI for both WIA and TAA programs when comparing program participants to nonparticipants with similar profiles (demographic and human capital). On average, the ROI more than doubles when WIA and TAA participants receive training. As Figure 1 shows, when training leads to a credential for WIA participants, the return is highest.

Figure 1 – Average Five-year return-on-investment for each dollar invested in WIA programs

The key factors driving the ROI are whether a participant gains employment after the program and how much they earn. Training and credentials have a much greater influence on WIA participants earnings and employment than on Trade Adjustment Assistance program participants. When disaggregated into individual types of training and credentials, three types of training and four different types of credentials had a positive and significant effect on WIA earnings, but none were significant for TAA. This is likely due to the fact that WIA participants tend to have limited labor market experience prior to the program making any enhancement extremely valuable toward improving labor market outcomes. They are also more likely to be receiving public assistance which means significant savings to the government once they are employed. All TAA participants, on the other hand, already have some experience and likely some training. Their employment and earnings are driven to a greater extent by the economy and labor market for their given trade. Because most have lost manufacturing jobs with decent wages, it is much more difficult to improve their labor market outcomes. Even if they gained employment, they were not likely on public assistance prior to the program so there would be limited savings to the government once they are employed.

Workforce Investment Act programs have historically deemphasized training (especially longer-term) in favor of placing job-seekers into the first job available no matter the job quality. My study confirms previous claims that training that leads to a credential increases labor market success. The findings add that there is a return on investment for government when sufficient dollars are invested in training that leads to a credential. When workforce program participants are able to secure higher paying more stable work, government both saves money on public assistance programs and collects taxes on the new wages.

While questions have been raised regarding the possible duplication of programs, this research shows that job seekers with different labor market profiles (such as WIA participants vs Trade Adjustment Assistance program participants) have different needs in terms of improving their earnings and employment outcomes. Whereas WIA participants with limited prior work experience benefit from almost any type of training and credential, TAA participants who have already been employed and likely have some sort of credential benefit more from educational credentials which may allow them to build on their prior work experience. This underscores the importance of flexibility afforded for each state to interpret workforce policies in a way that best suits their priorities and the characteristics of their labor force.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘What Is the Return on Investment for Public Workforce Programs? An Analysis of WIA and TAA in Virginia’, in State and Local Government Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2TTYDEu

About the author

Elsie Harper-Anderson – Virginia Commonwealth University

Elsie Harper-Anderson – Virginia Commonwealth University

Elsie Harper-Anderson is an Associate Professor and Director of the Doctoral Program in Public Policy and Management at Virginia Commonwealth University. Her research interests include workforce development and economic development and inclusive entrepreneurship. She received her Ph.D. in City and Regional Planning from the University of California, Berkley.