Being part of a political party means that someone is very likely to engage in political behavior like voting, protesting, donating to a campaign or writing to a public official. In new research, Laura Wray-Lake looks at how this link has evolved for politically active young people. Through survey research which charts nearly 13,000 young people’s political engagement, she finds that links to parties established at 18 last until at least 30; and that external events may also spark party-affiliated young people to be more politically active in certain ways.

Being part of a political party means that someone is very likely to engage in political behavior like voting, protesting, donating to a campaign or writing to a public official. In new research, Laura Wray-Lake looks at how this link has evolved for politically active young people. Through survey research which charts nearly 13,000 young people’s political engagement, she finds that links to parties established at 18 last until at least 30; and that external events may also spark party-affiliated young people to be more politically active in certain ways.

For decades, we have known that people affiliated with a major political party are more likely to vote, give money to candidates, and volunteer for campaigns than those with no party affiliation. In fact, being registered with a political party is considered one of the most reliable predictors of whether a person will vote. Political parties motivate political behavior by providing information, mobilizing members to act, and connecting people who share interests and ideologies.

However, the role of political parties on political behavior deserves a contemporary examination. In new research with colleagues Erin Arruda of the University of California and David Hopkins of Boston College, I argue that this association may not look the same for recent cohorts of youth (who are less likely to affiliate with a major political party than older cohorts), for different types of political behaviors (electoral versus non-electoral political actions), or over recent history (given historical changes in political engagement, citizenship norms, and the American party system).

To examine the role of party on youth political engagement, we used national US longitudinal Monitoring the Future data. The sample included high school seniors from 1976 to 2003. In our sample, 12,577 youth were surveyed at 18 and every other year until 30. This design allows us to examine both age-related change and historical change in youth political engagement.

We looked at two types of political engagement. Electoral participation included voting, giving money to a political candidate or cause, and working in a political campaign. Political voice entailed writing to public officials, participating in lawful demonstrations, and boycotting certain products or stores. Responses included no intentions to participate, some intentions to participate, and reports of already having participated.

Photo by Samuel Zeller on Unsplash

Party affiliation at 18 was categorized into Republicans (31.1 percent), Democrats (31.1 percent), and Others (37.8 percent, including Independent, other party, no preference, and undecided). These proportions show that among youth across cohorts, support for Republican and Democratic parties is relatively evenly split. Historical trends showed that youth are increasingly reporting no affiliation with either party.

Our findings offer three new insights into the relationship between political party and youth’s political engagement.

The positive effect of youth partisanship on electoral engagement is consistent across age and recent history. At 18, youth affiliated with Republican and Democratic parties reported higher electoral participation than others. As shown in Figure 1, this difference remained consistent across ages 18 to 30, showing partisan ties established in adolescence are lasting and meaningful across young adulthood. The pattern also remained consistent over time, indicating that the role of parties in motivating participation among young partisans has not changed from the 1970s through early 2000s.

Figure 1 – Party Differences on Electoral Participation across Age

Note. Responses are averaged across three types of electoral participation.

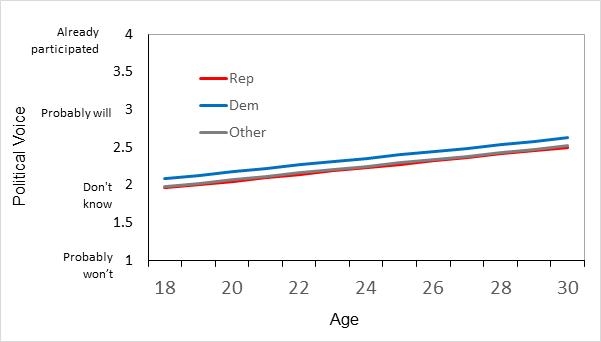

Democratic youth are more likely to express a political voice compared to other youth. In almost every year, young Democrats endorsed more political voice at age 18 than Republicans and non-affiliated youth. This average difference is shown in Figure 2. Yet, the differences were sometimes quite small and not always meaningful.

Figure 2 – Party Differences on Political Voice across Age

Political party affiliation plays a role in how youth develop political voice across young adulthood. Democratic youth showed greater increases in political voice from ages 18 to 30 than Republicans in 1979, 1996, and 2002, and Republican youth reported greater age-related increases in political voice than Democrats in 1980 and 2001. National political events may spark youth political voice in party-specific ways. Although such events cannot be pinpointed with certainty, possible events for Republican youth include the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 or Reagan’s election in 1980. Possible explanations for Democratic youth include the Three Mile Island Nuclear Spill (1979), the Rodney King trial verdict (1996), and the Iraq war (2002). The larger take-away is that youth are paying attention to what is going on in the world around them and are influenced by the social, political, and historical contexts in which they come of age. Youth’s likelihood of protesting and demonstrating across young adulthood may be partly determined by political and social events that are salient when they are adolescents.

Given evidence that youth’s partisan ties offer them meaningful connections to political action across ages 18 to 30 years, it is remarkable that political parties appear to place such a low priority on recruiting or mobilizing young people. In an age of closely fought and narrowly decided elections as well as an array of opportunities for non-electoral participation, it would be worthwhile for the major political parties—along with other social and educational institutions—to prioritize the incorporation of young adults into political society and to capitalize on historical moments that capture the attention of a rising generation of citizens.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The Party Goes On: US Young Adults’ Partisanship and Political Engagement Across Age and Historical Time’ in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2lT5YY1

About the author

Laura Wray-Lake – University of California, Los Angeles

Laura Wray-Lake – University of California, Los Angeles

Laura Wray-Lake is an associate professor of Social Welfare in the Luskin School of Public Affairs at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her program of research is centrally focused on the development of civic engagement across adolescence and young adulthood.