This year has seen several states adopt fetal “heartbeat” bills which would effectively ban abortions after the sixth week of pregnancy. Alex Garlick looks at why these bills are surfacing now, given that Roe v. Wade has been settled law for over 45 years. Drawing on a model of agenda setting, he argues that ambitious state legislators and Governors with designs on higher office are courting the support of anti-abortion interest groups, and that these same groups believe that Roe V. Wade may soon be overturned by the Supreme Court.

This year has seen several states adopt fetal “heartbeat” bills which would effectively ban abortions after the sixth week of pregnancy. Alex Garlick looks at why these bills are surfacing now, given that Roe v. Wade has been settled law for over 45 years. Drawing on a model of agenda setting, he argues that ambitious state legislators and Governors with designs on higher office are courting the support of anti-abortion interest groups, and that these same groups believe that Roe V. Wade may soon be overturned by the Supreme Court.

The South Carolina state legislature is currently considering H.3020, a bill to prohibit abortions if a fetus has a detectable heartbeat, which would effectively ban the procedure after women are about six weeks pregnant. South Carolina would be the fifth state controlled by Republicans to enact such a “Heartbeat” bill in 2019, joining Alabama, Ohio, Georgia and Missouri.

This flurry of activity is surprising, as these bills are heavily scrutinized in the court of public opinion. The abortion rights group NARAL wrote “These efforts to gut or overturn Roe v. Wade [the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision which made abortion legal] are out-of-step with overwhelming majorities of Americans, with public support for Roe at an all-time high.” A coalition of groups is applying pressure on businesses in these states. For example, Hollywood production companies are considering a boycott on filming in Georgia after Georgia passed its version the heartbeat law.

The progression of heartbeat bills is also surprising because the laws are unlikely to be implemented. Several federal judges have stuck down the policy; US District Judge Michael Barrett blocked implementation of the Ohio version of the law, writing “The law is well-settled that women possess a fundamental constitutional right of access to abortions.”

The timing of these bills raises two questions. First, why are groups pushing for action so hard right now? To answer this question, I will draw upon a classic model of agenda setting to explain why national political conditions are leading to state-level activity. Second, why are legislative leaders spending valuable agenda space on legislation that will likely be struck down immediately? I discuss how abortion policy’s national character incentivizes policymakers to face the intense scrutiny involved which this action and conclude with thoughts on the political and policy implications of the heartbeat bills.

Is a window of opportunity open?

The political scientist John Kingdon explains that certain issues rush onto the agenda when a “window of opportunity” opens. Windows of opportunity open when three “streams” — problems, policy, and politics — all interact.

The “problems” stream refers to issues in society that emerge and suddenly need resolution.

However, this does not describe abortions, as there is no evidence that abortions themselves have become more common. In fact, the incidence of abortions are going down in the United States; according to the CDC the abortion rate dropped 26 percent from 2006-2015. Although, the vibrant interest group community that has organized to oppose abortion rights considers the mere existence of the practice to be a problem.

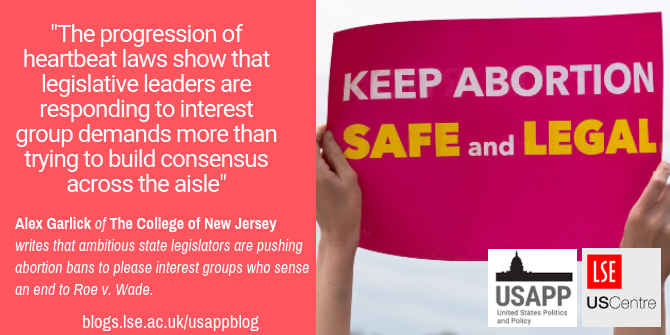

“Keep Abortion Safe And Legal sign at a Stop Abortion Bans Rally in St Paul, Minnesota” by Lorie Shaull is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Kingdon’s “policy” stream refers to potential solutions arising for problems. But “heartbeat bills” are not a new policy solution either. Ohio considered such a bill in 2011, and North Dakota and Arkansas passed them in 2013. So, while policy entrepreneurs may be coalescing on this solution to their perceived problem, it is not a newly available tool. Moreover, as Judge Barrett’s ruling indicated, heartbeat bills are not viable under existing caselaw.

Therefore, to the extent that a window of opportunity has opened, it must be linked to changes in the “political” stream. Specifically, Kingdon refers to changes in the political environment that invite action, which usually means an election. The Trump administration has a strong record of opposing abortion rights, but Donald Trump arrived in office in 2017. The action in 2019 is more likely a response to the recent appointments of Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. Kavanaugh appears to be the catalyzing element, as he replaced Anthony Kennedy, a justice with a more moderate voting record on abortion policy.

The anti-abortion rights groups believe that if the Supreme Court hears a case that could overturn Roe v. Wade, they will win. Faith2Action, a group which claims to have authored the model bill for the “Heartbeat Protection Act” told supporters that it “was counting” on Judge Barrett’s decision, and that “This is the way the Heartbeat Bill will reach the Supreme Court to do what it was always intended to do: move the line of allowable protection from viability (which is miles away from the goal of conception) to heartbeat (which is inches away).” While that outcome is by no means assured, it is a distinct possibility.

Why are state policymakers willing to pay the costs of the heartbeat bill?

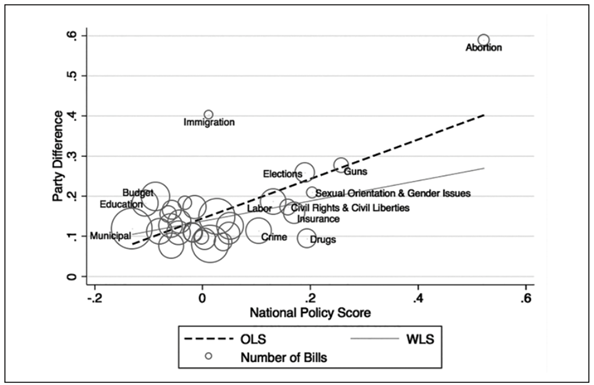

Just because activists perceive a window of opportunity to be open does not mean that policymakers will agree with their assessment. In past research, I discuss how policies that are prominent in national discourse can motivate rank-and-file legislators but repel senior policymakers that have more control over the agenda. Figure 1 shows that abortion is the most national issue, which I measure by observing the share of the interest group community lobbying on a state-level policy that also lobbies before Congress.

Figure 1 – More party difference on national policies, 2011-2014

Many backbench state legislators are ambitious: they would like to run for higher office at the state or national level. Endorsements from interest groups that operate at the national level, like the National Right to Life Committee, are extremely valuable in primary elections, so candidates are eager to please. From the groups’ perspective, national issues also offer the groups a chance to see which potential candidates will stand by their hardline positions in the face of scrutiny.

The calculus is different for senior policymakers in a party, who can be particularly sensitive to the costs that accompany national policies. For example, if the Hollywood boycott of Georgia materializes, and the state faces economic losses, a negative swing in public opinion before a key election could have lasting effects. In 2020, both of Georgia’s US Senate seats will be up for election, in addition to the entire state legislature.

Party leaders must see substantial benefits in order to cooperate with interest group demands. These interest groups offer substantial electoral resources, such as financial contributions and campaign volunteers that help them win elections up and down the ballot. Energizing these activists can help mobilize their base voters.

Moreover, governors can also be upwardly ambitious, and the heartbeat bill gives media attention to figures like Georgia’s Republican Governor Brian Kemp. Supporting hardline abortion legislation like the heartbeat bill may emerge as a litmus test in future Republican primaries for US Senate or president and supporting an early version could be a valuable marker for candidates to have laid down.

Looking Forward

Abortion rights activists have taken solace in statements from Senator Susan Collins (R-ME) that Justice Kavanaugh sees “Roe v. Wade as settled law.” However, these simultaneous actions demonstrate that anti-abortion rights activists sincerely believe the Supreme Court will overturn Roe v. Wade. Therefore, there is writing on the wall that the fate of Roe is more precarious than previously thought.

Second, this episode helps explain why some state legislatures are more polarized than others. My research shows that when there’s more national issues on the agenda roll-call votes are more divided by party. The progression of heartbeat laws show that legislative leaders are responding to interest group demands more than trying to build consensus across the aisle.

- This article was informed by the paper, ‘National Policies, Agendas, and Polarization in American State Legislatures: 2011 to 2014’ in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2lRE0Mz

About the author

Alex Garlick – The College of New Jersey

Alex Garlick – The College of New Jersey

Alex Garlick is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at The College of New Jersey. His research focuses on legislative institutions, particularly lobbying before Congress and the state legislatures.