While President Trump appears to have popularized its use, the deploying of contempt against political opponents is nothing new, write Kyle Mattes, David P. Redlawsk, and Ira J. Roseman. In new research, they find that contempt played a major role in two 2014 midterm Senate elections, with voters both perceiving it from campaign messaging, and being less likely to vote for a candidate the greater the level of contempt they felt for them.

While President Trump appears to have popularized its use, the deploying of contempt against political opponents is nothing new, write Kyle Mattes, David P. Redlawsk, and Ira J. Roseman. In new research, they find that contempt played a major role in two 2014 midterm Senate elections, with voters both perceiving it from campaign messaging, and being less likely to vote for a candidate the greater the level of contempt they felt for them.

Donald Trump recently proclaimed retired US Marine Corps General Jim Mattis to be the “world’s most overrated general.” As the target of such a Presidential pejorative, Mattis should not feel alone. A New York Times running tally shows that since becoming President, Trump—just on Twitter—has insulted 598 different people, places and things (as of May 24, 2019). The aim of his personal insults has often been to make the targets seem incompetent or corrupt, with the apparent goal of reducing positive feelings people might have for them.

Similarly, when a few Republicans criticized President Trump during the impeachment inquiry, he called them “human scum”. Here, Trump is not only asserting they are deeply flawed, he is questioning their worth as people. Because they are of low worth, we should not treat them with respect. Instead, we should treat them with contempt.

Contempt is the emotion accompanying appraisals of a person as beneath some standard. While Trump is the master purveyor of contempt—making it difficult nowadays to discuss contempt without referencing him—he is far from alone in making use of this emotion. Contemptuous politics has been impactful for quite some time. To understand why, consider the differences between contempt and another negative emotion, anger.

Though both are negative emotions, anger and contempt are, in some facets, opposites. Anger is a “hot” short-term emotion with a possibility of reconciliation. When we are angry with someone, we are more likely to confront them, often with a verbal attack, trying to change their behavior. On the other hand, contempt is a “cold” long-term emotion with an element of repulsion. When we feel contempt for someone, we are more likely to reject them and break off relations with them, perhaps because they are not worthy of further consideration.

“170127-D-GY869-031” by U.S. Secretary of Defense is licensed under CC BY 2.0, (DOD photo by U.S. Air Force Staff Sgt. Jette Carr)

Contempt is related to, but clearly distinguishable from, disgust. Contempt holds other people to be beneath some standard, and it is usually focused on character traits, many of which are highly relevant to politics (e.g., incompetence or corruption). Disgust, in contrast, is usually focused on offensive objects or conduct (e.g., body waste products or poor hygiene); in politics, it may be felt in response to political issues that some people perceive to violate purity norms (e.g., same sex marriage).

The importance of studying contempt is precisely due to its effects—it’s a long-term emotion that involves rejecting an individual or group. Contempt felt toward a political figure may be more damaging than anger because, as it is focused on the target’s traits, it is more difficult to reverse. So, encouraging contempt toward one’s political opponents could be a very effective strategy. However, the political science literature largely has been silent on this emotion.

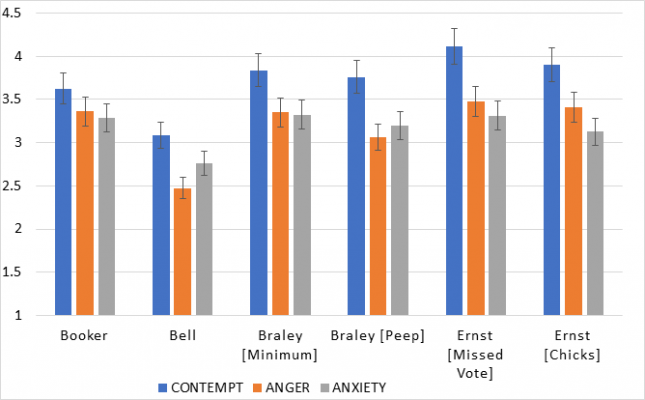

Our new research shows that contempt played a major role in the two 2014 US Senate races we studied: in Iowa and New Jersey. We surveyed a diverse sample of adults from both states in the weeks preceding the November 4, 2014 midterm election. Respondents viewed negative campaign advertisements (Iowa) and negative campaign statements (New Jersey) directed against each major party candidate in their respective states. After they viewed each video, we asked respondents about their perceptions of emotions in the videos—whether, and to what extent, each of the following six emotions were expressed: anger, anxiety, contempt, admiration, enthusiasm, and hope. Responses were on a five-point scale with higher numbers corresponding to greater intensity.

We found that of the three negative emotions measured, respondents perceived more contempt than anger or anxiety in every video. The figure below shows the means for each negative emotion in each of the six videos. Thus, contempt was perceived to a greater extent than two negative emotions often measured by political scientists.

Figure 1 – Perceived emotions toward targeted candidate

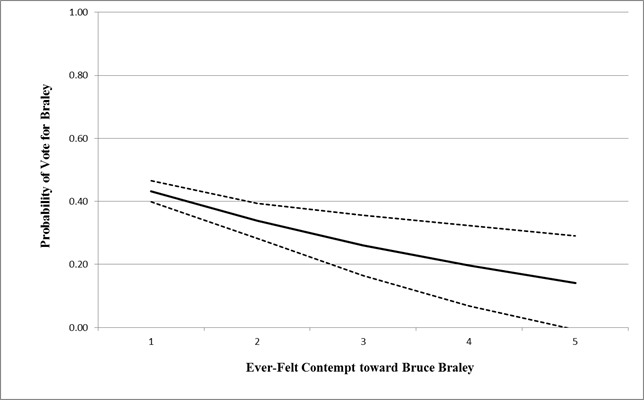

Though voters can perceive contempt from campaign messages, does contempt ultimately matter at the polls? In our study, we also asked respondents whether they had ever felt each of the six emotions toward each candidate, and if so, how strongly. We included the intensity of all emotions in a multinomial logistic regression predicting vote choice.

We found that respondents’ feelings of contempt toward candidates are of equal or greater significance than anger or anxiety in predicting voting intentions for three of the four Senate candidates. As an example, Figure 2 below shows how the predicted probabilities of a vote for Democrat Bruce Braley decline as the level of contempt for Braley increases.

Figure 2 – Voting probability and contempt for candidate

Regarding partisanship, we found that contempt matters for Republicans and Democrats, though we cannot say whether it matters equally for voters of both parties. It appears that the importance of contempt is election-specific or candidate-specific, rather than important only to voters in one political party or the other.

Voters often perceive contempt in candidates’ advertisements and statements, and they perceive contempt as distinct from other negative emotions. We also show that contempt predicts voting intentions as well or better than the much more often studied emotions of anxiety and anger. Thus, contempt can play a critical role in how voters perceive, evaluate, and react to political candidates. Failing to measure contempt can leave us blind to an important influence on political cognition and behavior. A serious and sustained effort to examine the influence of contempt politics is overdue.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Reprehensible, Laughable: The Role of Contempt in Negative Campaigning’, in American Politics Research.

- For readers further interested in the effects of contempt in politics, the authors have also published a study focusing on the 2016 Iowa GOP Caucuses.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2WVyA1c

Kyle Mattes – Florida International University

Kyle Mattes – Florida International University

Kyle Mattes is an associate professor of Political Science at Florida International University in Miami, FL. He publishes on negative campaigning, campaign strategy, and voter decision-making. He is co-author (with David P. Redlawsk) of The Positive Case for Negative Campaigning.

David P. Redlawsk – University of Delaware

David P. Redlawsk – University of Delaware

David P. Redlawsk is James R. Soles a professor and chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Delaware in Newark, His research focuses on the role of information in voter decision-making and on emotional responses to campaigns. He is co-author (with Kyle Mattes) of The Positive Case for Negative Campaigning.

Ira J. Roseman – Rutgers University

Ira J. Roseman – Rutgers University

Ira J. Roseman is a professor of Psychology at the Rutgers University campus in Camden, NJ. His model of the emotion system encompasses 17 emotions, including anger and contempt. His publications in political psychology include studies of emotions as predictors of responses to persuasive communications as well as voting and theories of ideological structure and individual attachment to strongly-held beliefs.