Our traditional understanding of the police is that they operate across a city, but in New Orleans, neighborhood associations have moved to create their own residential security districts with private patrols. Aaron Malone writes that the districts, which are mostly located in wealthy and racially similar areas, reinforce inequality, are ineffective against violent crime, and sidestep the difficult politics of police reforms that are needed.

Our traditional understanding of the police is that they operate across a city, but in New Orleans, neighborhood associations have moved to create their own residential security districts with private patrols. Aaron Malone writes that the districts, which are mostly located in wealthy and racially similar areas, reinforce inequality, are ineffective against violent crime, and sidestep the difficult politics of police reforms that are needed.

Urban public safety in the US has historically been dominated by city-wide police agencies. In New Orleans, a unique model has emerged of neighborhoods establishing formal security districts to address crime locally. This “residential security district model” created by neighborhood associations goes much farther than typical homeowner associations (HOAs) do by paying for extra police or private security patrols. Security district leaders have described the model as “taking a stand” to protect their neighborhoods in a city where the police were under federal oversight for poor performance. But the model has recreated policing as a ‘club good’ to which only some residents have access.

These neighborhood associations have re-scaled public safety as a neighborhood-level matter, but in the process are leaving behind most of the city’s working class and poor areas because only wealthy, demographically stable neighborhoods have been able to implement the model. And furthermore, security districts are only effective against property crimes like burglary, with no impact on the city’s pressing violent crime and murder problems.

Given its limited effectiveness and spatial constraints, the security district model could undermine much needed city-wide public safety improvements. Many of New Orleans’s wealthiest and most powerful residents have sidestepped the difficult politics of police reform and might be reluctant to support more funding for general policing because they are already paying extra for localized neighborhood patrols. The model has spread across the city in response to a sense of insecurity, but the approach is counterproductive and might end up perpetuating New Orleans’s public safety problems.

“I’ll Meet You at Three” by Thomas Hawk is licensed under CC BY NC 2.0

The Residential Security District Model

The security district model was developed by politically connected leaders in the city’s elite Uptown neighborhoods. They copied the legal structure of the longstanding downtown business improvement district but applied it to their residential neighborhoods instead. With help from legislators, security districts are written into state law and must be approved by residents in a referendum vote. Security district fees are then added directly to residents’ property taxes, averaging 10 percent of the total bill. As of 2012, New Orleans had twenty-five active districts that controlled combined annual revenues over $5 million and included an estimated 16 percent of city residents within their boundaries. Ten more districts have formed in suburbs just beyond the city limits.

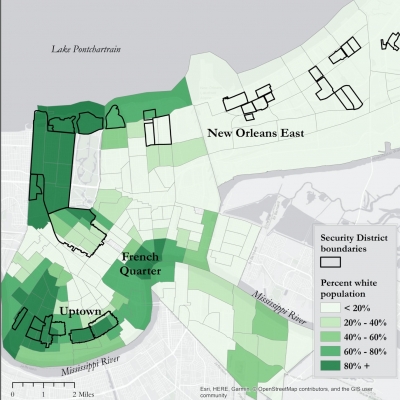

Security districts are disproportionately located in wealthy areas, with the median household income nearly 40 percent higher than the city overall. The neighborhoods that form security districts also tend to be racially similar. In many cases the areas have greater than 80 percent residents of a single race – security districts have been embraced by the city’s white and black elites alike (Figure 1). The model has been surprisingly uncontroversial, except for the local American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) branch speaking out against an early district (but not taking a position against the twenty-plus others that have formed since). The rare cases of voters rejecting security district referendums have occurred in gentrifying or racially diverse neighborhoods.

Figure 1 – Security districts and city racial demographics. Percent white by Census block groups, 2010

The Politics and Implications of Security Districts

In the end, it seems that most residents, leaders, and politicians have embraced the notion of security districts as a grassroots phenomenon, neighborhoods standing up for their own safety in the face of failing city police services. However, it is critical to emphasize that security districts reinforce inequality, are ineffective against violent crime, and sidestep desperately needed debates around public safety and criminal justice reform. The feel-good story about taking a stand within each neighborhood masks a reality that is more complex and problematic.

This example has relevance beyond New Orleans, even if it is the only city thus far to see residents implement the model. Security districts might be seen as filling a niche that exists in many cities, where wealthy enclaves in older parts of the city have limited organizational options compared to the homeowner associations (HOA) model implemented in new developments. The New Orleans security district model overcomes perceived collective action or free-rider problems by making contributions for neighborhood patrols legally binding. Residents modified the business improvement district model to retrofit old neighborhoods with some of the powers of a modern HOA.

The security district example provides important insights on the geographic concept of “policy mobility.” The lessons learned from studying how security districts spread from neighborhood to neighborhood are also applicable to understand the spread of policy trends on national and global scales. While the security district model has thus far remained anonymous, largely invisible to policymakers outside New Orleans, it could be mobilized in the future. Much like the spread of security districts within the city, broader patterns of policy mobilization can be driven by a sense of success or a marketing narrative even when concrete results are lacking. The story of New Orleans’s security districts helps us understand how questionable or counter-productive policy models can nonetheless find an audience and spread.

- This article is based on the paper,’(Im)mobile and (Un)successful? A policy mobilities approach to New Orleans’s residential security taxing districts’ in Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2OP5U7Z

About the author

Aaron Malone – Colorado School of Mines

Aaron Malone – Colorado School of Mines

Aaron Malone completed his PhD in Geography from the University of Colorado, Boulder. His research takes a geographic perspective on policy topics ranging from neighborhood security to international migration to community development. Currently he is a post-doctoral research fellow at the Center for Mining Sustainability at the Colorado School of Mines, researching the impacts of informal gold mining in southern Peru.