As one of the earliest states to vote in a presidential nomination primary season, New Hampshire is known for the retail politics candidates must undertake in order to win support. But as upset wins have become less common, have presidential hopefuls been spending less time in the Granite State? Collecting 17 years of data from candidates’ events, Jennifer C. Lucas, Christopher J. Galdieri, and Brian O’Connor find that front-runner candidates are visiting New Hampshire less, and when they do, they do more party events and town halls, and fewer “meet and greets” with voters.

As one of the earliest states to vote in a presidential nomination primary season, New Hampshire is known for the retail politics candidates must undertake in order to win support. But as upset wins have become less common, have presidential hopefuls been spending less time in the Granite State? Collecting 17 years of data from candidates’ events, Jennifer C. Lucas, Christopher J. Galdieri, and Brian O’Connor find that front-runner candidates are visiting New Hampshire less, and when they do, they do more party events and town halls, and fewer “meet and greets” with voters.

Recently, a local Democratic Party chair was quoted about the 2020 Democratic primary race in New Hampshire as saying, “From my perspective, both Biden and Bernie are more counting on their name recognition than the retail politics that we’re known for here in New Hampshire.” Are candidates spending less time in New Hampshire? Is this true of all candidates, or, as this party activist noted, is it more true of the front-runners? This is an important question because it speaks to the very heart of the argument for the New Hampshire primary: as former New Hampshire Governor Hugh Gregg wrote, “It’s pretty hard for a candidate to fake it when talking face to face”

Ahead of the first election-year primary (and only the second nominating contest after the Iowa Caucuses), voters in New Hampshire, political folklore has it, turn out to “kick the tires” on candidates, asking tough questions, raising issues of concern to local communities without the filter of the media. Ever since Jimmy Carter’s rise to national prominence in 1976, there have been many less well-known candidates that have spent significant time in New Hampshire trying to shake enough hands and meet enough voters to create the momentum that would carry them forward to the nomination. Yet genuine upsets by little-known candidates have become rare: John McCain and Hillary Clinton were far from obscure when they unexpectedly won their respective primaries in 2000 and 2008, and Bernie Sanders’ win in 2016 was no surprise by the time it took place.

Does retail politicking still define the New Hampshire primary?

To examine changes in the New Hampshire primary over time, we collected data about every presidential candidate event we could identify from reliable public sources from the 2003/2004 election cycle through the 2019/2020 election cycle. We included any event held in the state beginning in January of the year before the primary (i.e. 2008 includes events held after January 1st, 2007). Since this analysis was done before the primary, we cut off the analysis 10 days before the Iowa caucuses. While the dates of the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary vary somewhat from year to year, they are typically sometime between early January and early February. We do not include candidates who dropped out before December 1st, as they would skew the data.

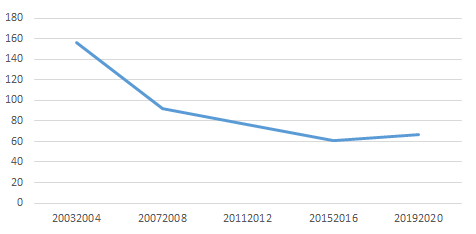

First, we looked at whether the number of candidate visits varies across time. Figure 1 indicates that the median number of presidential visits per candidate has indeed declined. Even if the 2004 election cycle was artificially high, the median number of visits to the state dropped from 92 in 2008 to 67 in the 2020 race.

Figure 1 – Median Presidential Candidate Events in New Hampshire, 2004-2020

This decline could be driven by two different groups: Lower tier candidates trying to make a name for themselves may choose to focus on Iowa’s caucuses, rather than New Hampshire, as the more viable option for establishing themselves as contenders, or front-runner candidates, who have more money and fame may be opting to rely on media or other traditional campaign tactics, like direct mail, to contact voters and supplement their in-person events.

“Hillary Clinton supporters” by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

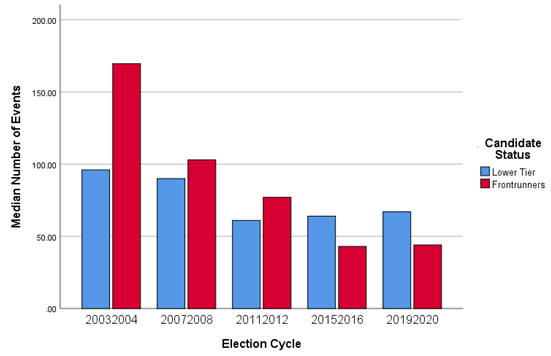

Figure 2 shows the breakdown for the two types of candidates. We define front-runners as candidates polling one of the top two spots in the last month before the primary, and all other candidates are grouped as lower tier candidates. Interestingly, the decline in the overall number of visits to the state in recent election cycles seems to be at least partly due to fewer visits from the front-runners. In the 2004, 2008, and 2012 races, front-runners, on average, held more events in New Hampshire than lower tier candidates. However, in the 2016 and 2020 cycles, the front-runner candidates held fewer events than the lower tier candidates. While 2016 can be partly explained by then-candidate Trump’s fewer visits and large rallies, it does not explain fewer visits from this year’s front-runners, Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden.

Figure 2 – Median Number of Presidential Candidate Events, 2004-2020

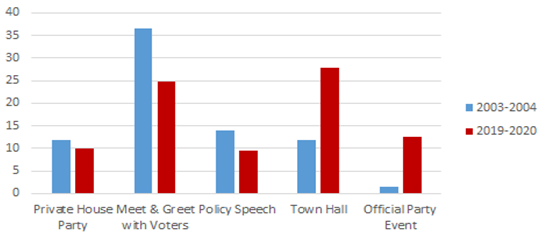

On the other hand, while the number of events has declined, the types of events being held in the state have been similar, with a few significant exceptions. The New Hampshire primary is known for its retail politics. To see whether the types of events had also changed over this period, we coded events by type including private house parties, meet and greets with voters (where the candidates stop and shake hands with voters in restaurants or other public spots), policy speeches, town halls, or organized party events (i.e. meetings with Young Democrats or local party members).

Figure 3 shows the percent of the total number of events that fit into each type for 2003/2004 and 2019/2020. While the number of house parties has remained steady, there has been a decline in the number of meet and greets with voters. However, there have been more town halls, which are often, but not always, a chance for voters to ask questions of the candidates. This suggests there may be less of a chance for random voters to meet the candidate, and instead meet only those that seek them out. On the other hand, the traditional town hall may offer voters a chance to ask questions but may also give the campaign some more control over the event.

One interesting increase has been in the number of official party events. It appears that the state and local parties are increasingly sponsoring events to bring candidates to meet local partisans. Given how polarized the electorate is and that activists are a group of voters that are likely to turn out to vote, it makes sense that these events would attract presidential candidates.

Figure 3 – Types of New Hampshire Presidential Events, 2004 vs. 2020

In sum, it appears that presidential candidates are spending less time in New Hampshire, especially front-runners. When the candidates do appear, it seems as though they are still holding retail politics events, though the local and state parties appear to be increasingly involved. It is not clear whether this is a trend that will continue; it may be that Trump’s celebrity status allowed him to circumvent retail politicking in ways that may not hold true for other candidates.

For those who want voters to “kick the tires” on candidates and ask them the hard questions, there may be fewer opportunities for retail politics than there once were.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2S64GXA

About the authors

Jennifer C. Lucas – Saint Anselm College

Jennifer C. Lucas – Saint Anselm College

Jennifer C. Lucas is Professor and Chair of the Department of Politics at Saint Anselm College. She teaches courses including American government, women and politics, and congressional politics. Her work on women congressional candidates has appeared in Gender & Politics, Social Science Quarterly, and American Politics Research.

Christopher J. Galdieri – Saint Anselm College

Christopher J. Galdieri – Saint Anselm College

Christopher J. Galdieri is Associate Professor of Politics at Saint Anselm College. He teaches courses in American government and on topics ranging from the presidency to constitutional law to the New Hampshire primary. He has published Stranger in a Strange State: The Politics of Carpetbagging from Robert Kennedy to Scott Brown, and Donald Trump and New Hampshire Politics. He is the coeditor (with Jennifer C. Lucas and Tauna S. Sisco) of several books, including Conventional Wisdom, Parties, and Broken Barriers in the 2016 Election and The Role of Twitter in the 2016 US Election.

Brian O’Connor

Brian O’Connor

Brian O’Connor is a Policy Analyst at the Massachusetts House of Representatives. He received a M.A. in Political Science from the University of New Hampshire in 2018, and a B.A. in Politics from Saint Anselm College.