In times of war, courts tend to conform to the government’s agenda. But in new research, Rebecca Reid, Susanne Schorpp, and Susan Johnson find that this pattern is less pronounced for diverse panels of judges. Using data on men and women judges’ decision-making on US appellate courts in search and seizure cases during the War on Terror, they determine that male judges serving in all male panels are most affected by national security threats and respond by deferring to the government. Panels with women, by contrast, are more likely to generate decisions that are more consistent with peacetime checks on government power.

In times of war, courts tend to conform to the government’s agenda. But in new research, Rebecca Reid, Susanne Schorpp, and Susan Johnson find that this pattern is less pronounced for diverse panels of judges. Using data on men and women judges’ decision-making on US appellate courts in search and seizure cases during the War on Terror, they determine that male judges serving in all male panels are most affected by national security threats and respond by deferring to the government. Panels with women, by contrast, are more likely to generate decisions that are more consistent with peacetime checks on government power.

If 2018 was another year of the woman–with more women elected to the House of Representatives than in any other election–the news did not reach the federal courts. What had been the most diverse federal judiciary ever under President Obama, has now reverted to a majority white male institution. Whereas 42 percent of Obama’s judicial appointees were women, the percentage of women judges appointed to the federal judiciary by President Trump currently stands at 22 percent. How does that diversity, or the lack of it, influence court outcomes? Our contribution to this discussion centers on the potential of gender diversity to disrupt groupthink. More precisely, we look at how gender diversity on the federal judiciary can make it less likely for judges to defer to the executive during times of war. Since war, as Madison once stated, “is in fact the true nurse of executive aggrandizement,” understanding the forces that tug at the separation of powers structure in times of war can provide us with an understanding of the larger dynamics influencing the health of a democratic republic.

War increases judicial deference because judges, like the general public, prefer security concerns to civil liberties. Yet, the effects of war most directly impact male judges. National security threat generates incentives for men to validate male group membership by performing more ‘masculine’ traits, such as those associated with the provision of security and safety against perceived threats.

At the same time, perceptions of threat mean that people are more likely to identify with and favor people who are like them. This increased importance of group identity leads to intensified pressure for in-group conformism that can lead to groupthink, a “pattern of concurrence-seeking … when a ‘we’ feeling of solidarity is running high,” such as the “rally ’round the flag effect” known to occur nation-wide during the onset of war.

Since US Courts of Appeals routinely decide cases in three-judge panels, we argue that all-male judicial appellate court panels should therefore be most susceptible to the pressure for conforming to behavior that validates their in-group membership, which, as stated above, values (“masculine”) security efforts. This dynamic diminishes disagreement within the group, since under groupthink “[m]embers consider loyalty to the group the highest form of morality.” In times of war, the beneficiary of this security-favoring groupthink is the government, which tends to “not let a good crisis go to waste,” as they pass laws to restrict civil liberties in the name of security.

The presence of women judges can mitigate the effects of war-induced groupthink in male panels as research shows that panel diversity may provide a safeguard against groupthink and that judges respond to the votes or arguments of other judges. While we do not assert that women are unaffected by war, we do not expect war to affect women in the same manner as men because of the gendered nature of threat response stereotypes. Furthermore, women may be less likely than their male counterparts to limit the protection of civil liberties in wartime due to their experience with devaluation, exclusion, violence, and discrimination. Women may be more likely to uphold civil liberties in the face of war because they perceive the cost associated with limiting civil liberties as higher than their male colleagues. Thus, we suggest that gender diversification on the bench can lower the probability of groupthink.

“US Court of Appeal” by Karen Neoh is licensed under CC BY 2.0

All-male panels should, under this proposition, be more inclined to decide cases in favor of the government in times of war than peace – unlike mixed panels. Put another way, we expect the voting patterns of male judges who sit in panels with female judges to be unaffected by war, whereas those sitting in all-male panels should show an increased propensity to support the government in times of war.

Using all published search and seizure cases decided in the US Courts of Appeals (with thanks to Rachael Hinkle for generously sharing her data with us) across 30 years, we compare peacetime and wartime decisions across all-male panels and mixed panels to evaluate the influence of the presence of women on male appellate judge votes.

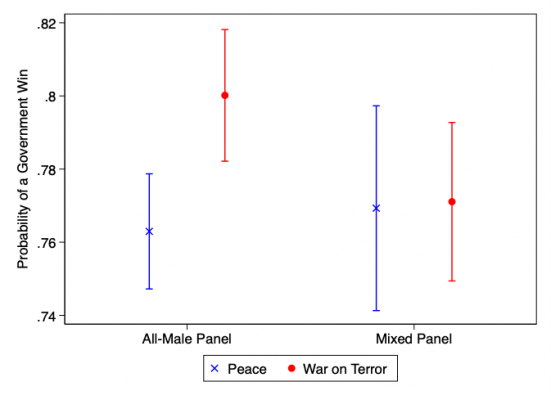

Figure 1 shows the probability of a vote in favor of the government across times of peace and the War on Terror for male judges who sat on all-male panels (left side of the figure) and those who sat on mixed panels (right side). The red line indicates the level of government deference during times of war, while the blue line depicts level of deference during times of peace. The two lines for all-male panels show that judges in all-male panels are more deferential to the government during war. This deference does not occur when women are on the panel. When women sit on the court, wartime decisions by male judges are indistinguishable from peacetime decisions, as indicated by the consistent voting patterns for mixed panels across times of war and peace. Indeed, a male judge is less likely to vote for the government by 3.8 percentage points when sitting in a diverse (mixed) panel during war than when in all-male panels.

Figure 1 – Probability of Court Deference Across Panel Composition

Our findings provide support for groupthink theory’s influence on judging, which suggests that in times of war, masculine tendencies towards security and protection are self-reinforcing in all-male panels, but that the presence of women on the panel moderates these tendencies. Our results suggest the push to conform is minimized or lessened when more people from diverse backgrounds sit on panels. The implication then is that diversification of the courts could improve the rule of law by ensuring consistent judicial outcomes across political environments.

- This article is based on the paper, “Trading Liberties for Security: Groupthink, Gender, and 9/11 Effects on US Appellate Decision Making,” in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2HrR4iU

About the authors

Rebecca Reid – University of Texas at El Paso

Rebecca Reid – University of Texas at El Paso

Rebecca Reid is an assistant professor of Political Science at the University of Texas at El Paso. Her research interests include judicial politics, comparative courts, international law, and human rights.

Susanne Schorpp – Georgia State University

Susanne Schorpp – Georgia State University

Susanne Schorpp is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Georgia State University. Her main area of research is in judicial politics, with a focus on separation of powers, rights protection, and court legitimacy.

Susan Johnson – University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Susan Johnson – University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Susan W. Johnson is an associate professor of Political Science at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on women and courts and judicial politics primarily in Canada and the United States.