In the US, lawmaking at the state level is often heavily linked to the ideology of the party which controls the legislature. Evidenced Based Policy, on the other hand, provides a means for lawmakers to develop measures based on research and data. In new research, Luke Yingling and Daniel J. Mallinson look at what drives the adoption of Evidence Based Policy across the states, finding that it is often motivated by reasons of practicality and electoral self-interest rather than a desire to improve policy outcomes.

In the US, lawmaking at the state level is often heavily linked to the ideology of the party which controls the legislature. Evidenced Based Policy, on the other hand, provides a means for lawmakers to develop measures based on research and data. In new research, Luke Yingling and Daniel J. Mallinson look at what drives the adoption of Evidence Based Policy across the states, finding that it is often motivated by reasons of practicality and electoral self-interest rather than a desire to improve policy outcomes.

Evidence-Based Policy (EBP) – where policymaking is informed by research and analysis rather than anecdote and inertia – is more than political cliché. Nonetheless, using the term can be beneficial to politicians’ electoral prospects which makes them more likely to adopt laws which have the label. States craft and implement innovative policies, even those tailored to address similar problems, in very different ways. Unsurprisingly, the construction, purpose, and outcomes of these laws are influenced by the institutions, parties, and office-holders who craft them. In new research, we find that Democratic governors, Republican legislatures, and how innovative a state is are significant predictors of EBP adoption in the American states. However, our study also unveils the practical rather than ideological motivations underlying state adoption of EBP.

We find that the adoption of evidence-based policies is driven more by self-interest than altruism. Although engagement with EBP can produce more efficient and effective government, it can also supply new levers of control to politicians and bureaucrats, which in turn can be used to help them to win elections. It is the powers EBP offers, which can be used to centralize control of executive functions, as well as to change budgets, that incentivize adoption.

What are the incentives around using Evidence Based Policies?

To understand the political incentives that EBP offer, we need to first understand the design of the institutions that develop them. Governors are popularly elected in statewide elections and thus have a natural incentive to appeal to a broad base of voters. When seeking new benefits (in the form of new laws, repeal of old laws, new programs, cessation of programs, tax cuts or increases, etc.) for their citizens, self-interest and the desire to achieve re-election compels governors to adopt policies which will have broad-based, positive impacts. Legislators, however, are elected by districts within a state. Their primary incentive is to deliver benefits for their districts. Thus, legislators have a natural incentive to strive for more tailored benefits.

Political parties add another layer of interests to this scenario. Democratic governors receive an electoral boost in years that they grow their state budget. Republican governors, however, are punished by voters for budgetary expansions. Because using EBP requires the establishment of data infrastructure, costs money, Democratic governors stand to benefit more electorally from this spending. Nevertheless, the efficiency and effectiveness benefits derived from EBP can reduce budgets, despite initial costs. Thus, EBP allows legislatures to improve the way state government works and potentially reduce budgets without expending significant capital necessary for winning re-election, which is especially critical to more professionalized legislatures. Accordingly, because Republicans perform poorly in elections when their administrations have seen spending growth, EBP can help them to win elections. Therefore, it is the interplay of political and institutional incentives that motivate the adoption of Evidence Based Policy (EBP).

“Pushpins in a map over the U.S.A.” by Marc Levin is licensed under CC BY 2.0

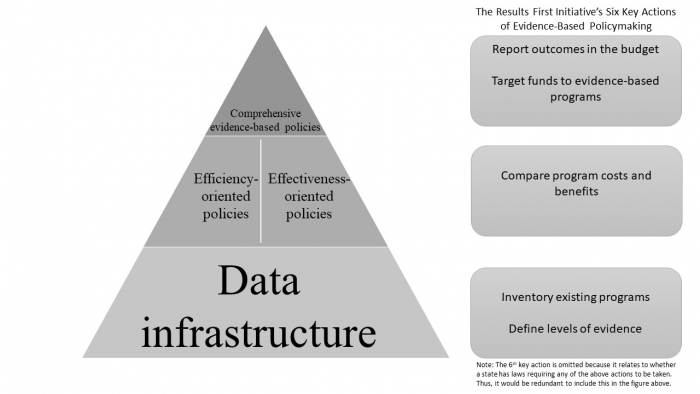

Until this study, there had not been a comprehensive inspection of EBP adoption in the American states. That is due, in part, to just how difficult it is to measure EBP. Declaring that a policy is evidence-based has a legitimizing effect that can help garner support for proposed laws. Thus, many politicians have made use of the term to generate political capital. Aside from its politicization, the term is vague. Accordingly, its meaning must be unpacked to objectively measure it for the purposes of our study. Given that many legislators, academics, and practitioners disagree about which sources are evidence-based, we define evidence-based policies not by the information used to shape them, but by their features. Some features, such as data collection, are hallmarks of evidence-based policy. These features form a hierarchy (Figure 1) where lower-level aspects form the necessary formation for higher level features, like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. We were aided in developing this hierarchy by the work of the Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative.

Figure 1 – Hierarchy of Evidence-Based Policy Features

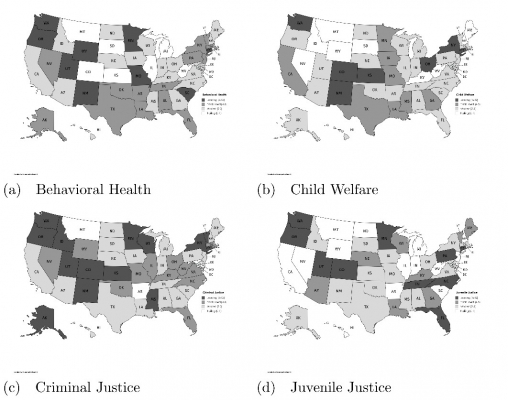

By measuring the presence or absence of these features, we can gauge the extent to which states have adopted evidence-based policies in distinct policy areas. Our study delves into four policy areas: criminal justice, juvenile justice, behavioral health, and child welfare (Figure 2). In addition to these, we tallied the cumulative scores of each state based on their scores across the four policy areas. While some states, such as Utah and Washington, excelled in most policy areas, earning them high cumulative scores, others, such as Montana and Michigan, scored poorly across the spectrum.

Figure 2 – Variation in Four Evidence-Based Policy Areas in the American States

How Evidence Based Policy can be adopted more widely

Our study offers a blueprint for identification of states that are ripe for adoption of EBP. This can be useful for political groups that want to advance EBP for their causes. It also helps us better understand how institutional incentives shape policymaking, even in EBP. The information in our study is especially useful to those advancing policies in the areas of criminal justice, juvenile justice, behavioral health, and child welfare, as those are the focus of our study.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Explaining variation in evidence-based policy making in the American states’ in Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2XCdGGh

About the authors

Luke Yingling – West Virginia University

Luke Yingling – West Virginia University

Luke Yingling is a law student at West Virginia University College of Law. He holds a Masters in Public Administration and has worked in the public sector during his education in the areas of drug policy, behavioral health, and criminal justice.

Daniel Mallinson – Pennsylvania State University-Harrisburg

Daniel Mallinson – Pennsylvania State University-Harrisburg

Daniel Mallinson is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Administration at Penn State Harrisburg’s School of Public Affairs. His research focuses on policy diffusion, pedagogy, and marijuana, energy and environmental policy.