Many believe that if a Black person simply speaks ‘properly’, ‘sounds like a native English speaker’, or uses ‘Standard English’, their language will be accepted in the academic spaces of universities and schools. But new research from Patriann Smith shows that using ‘Standard English’ in such spaces within the US when a speaker is a Black immigrant may not always translate into acceptance. She argues that Black speakers would do well to reject the myth that trying to speak ‘Standard English’ will result in acceptance and success.

Many believe that if a Black person simply speaks ‘properly’, ‘sounds like a native English speaker’, or uses ‘Standard English’, their language will be accepted in the academic spaces of universities and schools. But new research from Patriann Smith shows that using ‘Standard English’ in such spaces within the US when a speaker is a Black immigrant may not always translate into acceptance. She argues that Black speakers would do well to reject the myth that trying to speak ‘Standard English’ will result in acceptance and success.

The recent events across the globe that have erupted following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in May caused ripple effects across many spaces where racialization occurs daily against Black and brown bodies. One of these often-overlooked spaces is in academic context of universities and schools. Black and brown speakers in this space who wish to advance must illustrate that they can use language and use it well. To use language well in the US context, more often than not, means to write and speak English in ways that are acceptable in academic spaces. These academic spaces have dictated for a very long time how speakers must use ‘Standard English’ if they are to be accepted. And for those speakers who are Black, academic spaces have repeatedly suggested to them that if only they will adjust what is often considered their ‘broken English’ speaking, they will be able to benefit from the privilege of advancement that academia provides.

What does this mean for Black American English speakers?

The ‘Standard English’ that seems acceptable in the US academy is known as Standard American English, an English that looks, feels and sounds American, and is supposedly spoken by the predominantly White US majority. This is clear because the Englishes of Black Americans are largely labeled African American Vernacular English (AAVE) or African American English (AAE), implying that Black Americans naturally default to speaking vernacular English. This situation has been further made worse such that the Oxford Handbook of African American Language recently emphasized the need for the use of the term African American Standard English (AASE). This emphasis arose because of the tendency of so many to distinguish between AAE and Standard English in ways that implied that all the language of Black Americans was largely ‘nonstandard.’

The approach to ‘Standard English’ adopted by US academia mirrors the prevailing notion of Black American language as being nonstandard, and so does the largely absent terminology, AASE, across language discourses in academic circles and American contexts. Such underlying ways of thinking about and describing Standard English in connection with and as typically used by White populations in the US context have said to Black Americans, for a very long time: ‘Your Englishes, by and large, are primarily vernacular Englishes,’ despite the fact that Black Americans use AASE daily across a myriad of contexts in the US to thrive. These underlying ways of thinking have also implicitly reinforced the notion that White norms about language are to be aspired to and will bring with them the success desired if ‘Standard Englishes’ used can only just mirror White language norms. Yet instead, what has happened is that ways of thinking about ‘Standard English’ in academic spaces have historically and continue to cause Black Americans to feel inferior and illegitimate because of their race, no matter how well they use English — standard or not.

What does this mean for Black immigrant English speakers?

When Black immigrants arrive in the US, they become subsumed into the broader Black American population. As they work in the academy, they continue to use their own versions of ‘Standard English’ that they believe are accepted in formal spaces. Like their Black American peers who use the often-overlooked African American Standard English (AASE), Black immigrants use ‘Standard Englishes’ such as Ghanaian English, Trinidadian Standard English, and Jamaican Standard English. Many of them have used these Englishes in their home countries where there are often mostly Black speakers such as themselves. They do not expect that these Englishes might seem different to their peers in the US academy because the Englishes have previously been accepted in the academic spaces of their home countries. But they are in for a surprise. The ‘Standard Englishes’ that seemed acceptable to them in their home countries are not often acceptable to their US peers even though they are ‘standard’. In fact, many find that there is discrimination against how they use their ‘Standard Englishes’ even when they make an effort to adjust. For the Black immigrant, this realization causes confusion.

Unlike their Black American peers, Black immigrants do not often realize that not only are they using Englishes that seem different, but also, that they are now Black in a White world. They do not realize that the academic system is set up to expect them to use ‘Standard English’ in acceptable ways. Many are also oblivious to the notion that no matter how much they use their ‘Standard Englishes’ as Black people, their language will not be accepted in ways that necessarily translate into acceptance and success. Others who had been opposed to vernacular uses of English in their home countries, for the first time, often remember how terrible they made students feel when using these vernacular Englishes in formal academic spaces. And still others think that if only they can use the Standard American English as they should, they may be able to thrive.

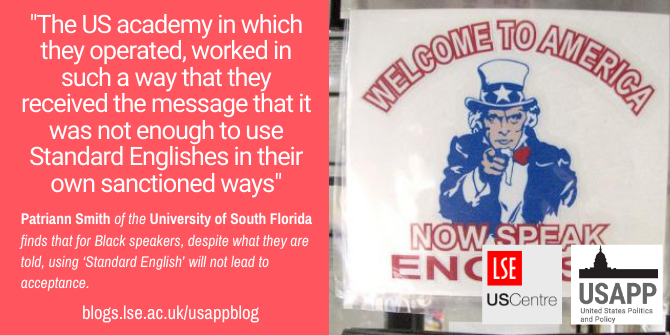

“Welcome to America, indeed” by CGP Grey is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0, https://www.cgpgrey.com/

Studying how race and language affect Black immigrants’ uses of Englishes in the US academy

Exploring the confusion faced by Black immigrants as they grapple with being Black, finding their ‘Standard Englishes’ unaccepted, and being foreigners in the US academy is one that I believed, could add nuance to how we think about the supposed acceptance of standard Englishes in academic spaces. To examine their experiences, I asked seven Black immigrant educators from the Bahamas, Ghana, Jamaica, St. Lucia, and Trinidad to describe how they used their ‘Standard Englishes’ when they migrated to the US. I also asked them to describe how they coped with the challenges they faced as they used these Englishes. I chose educators because Colleges of Education are a primary space where academia where teachers, educators, administrators, and others are tasked to guide teachers to address the needs of diverse K-12 students in a myriad of subject areas. I also chose educators because Colleges of Education are increasingly responsible for addressing diversity on university campuses, but do not often recognize how their international policies can impact K-12 students. I chose Black immigrant faculty because of the intersecting factors of race, migration, and linguistic difference, that position them as uniquely positioned to speak to the ways in which the use of Standard English in the US academy affects them. And I chose Black immigrants who were users of Standard Englishes in their home countries and teachers in these countries before migrating to the US.

Dismantling the myth that all ‘Standard Englishes’ are created equal

In my research, I found that Black immigrant speakers indicated that their ‘Standard Englishes’ were not accepted by many and in many contexts within and beyond the US academy. They were made to view these Englishes as illegitimate despite their previous beliefs that they were legitimate speakers of the ‘Standard Englishes’ used in their home countries. These feelings of illegitimacy came from the negative reactions of individuals to their connotations and vocabulary, from the racial expectations associated with their accents, and from the lack of respect for the interplay among their race, foreignness and accents.

The Black immigrant speakers experienced weird looks, disregard of their communication and the content of their conversations, silence in response to what they attempted to say, responses from others that were disconnected from the. messages they tried to convey, perceptions of unintelligibility. In turn, they withdrew emotionally and socially, felt hurt, were in shock, often lost for words in conversation, stopped caring, stopped expressing themselves, and had less to say overall. As they processed these experiences, the speakers tried to use language in ways that could enable them to feel legitimate by slowing down their speech, managing their use of vocabulary, code switching, redirecting individuals to learn about their own vocabulary, intentionally managing rapport, hypothesizing about expectations of the professorial audience when writing academically, and changing from British to American writing. They explained that their friends, fraternities, self-talk, colleagues, as well as understanding the social norms surrounding the geographical context into which they had migrated, all enabled them to work towards this legitimacy.

Overall, the finding that caught my attention was that the Black speakers felt that the burden was on them to try to adapt to Standard American English norms despite their already legitimized status as speakers of ‘Standard Englishes’. In essence, the US academy in which they operated, worked in such a way that they received the message that it was not enough to use Standard Englishes in their own sanctioned ways. They learned that as Black speakers, even though they spoke a ‘standard’, there was a supposedly superior standard primarily spoken by White Americans and sanctioned by White norms to which they should aspire. Certain Black speakers such as the Ghanaian immigrant faculty member did not adjust their way of using Standard English. They said that they recognized that the predominantly White K-12 students whom they taught never positioned their Ghanaian ‘Standard English’ as a source of illegitimacy and so they wondered why White adults tended to do so. Other Black speakers from the study decided when, where, and how they would adjust their use of standard Englishes based on their understandings about new expectations of them based on race, language and foreignness.

The need to have Eurocentric systems carry the burden that Black immigrant (and Black American) speakers bear

Academic systems that continue to legitimize White language norms that privilege one Standard English over others place an undue burden on Black speakers to adjust to these norms. If the touted expectation is that the US academy subscribes to ‘Standard English’ as the dominant medium for imparting knowledge, then there is an expectation that any form of standardized English should be accepted. The US academy and other spaces where English functions as dominant can be intentional about legitimizing all ‘Standard Englishes’ in policies that affect Black immigrant (and American) faculty, particularly those that affect their advancement through academia. Already, certain White students have shown Black immigrant faculty that they are eager to do so. Now, Eurocentric systems can as well.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2Q2h9JN

About the author

Patriann Smith – University of South Florida

Patriann Smith – University of South Florida

Patriann Smith is an Assistant Professor of Literacy and Diversity at the University of South Florida. Patriann’s research focuses on cross-cultural and cross-linguistic considerations for literacy instruction and assessment in the learning and experiences of Black immigrant adolescents and educators. Her research has appeared in journals such as the American Educational Research Journal, Teachers College Record, International Journal of Testing, The Urban Review, The Journal of Black Studies, Reading Psychology, International Journal of Multicultural Education, Theory into Practice, and Teaching and Teacher Education. She is Co-Editor of the Handbook of Research on Cross-Cultural Approaches to Language and literacy development and author of the forthcoming book titled Black Immigrant Literacies: Translanguaging for Success with Cambridge University Press.

1 Comments