When it wants to promote democracy in other countries, the US has a number of options, ranging from foreign aid to economic sanctions to military intervention. But how do Americans feel about these different ways of intervening? In new survey research, Abel Escribà-Folch, Lala Muradova, and Toni Rodon find that Americans are more supportive of intervening in autocratic countries which do not hold elections, and are not US allies. But past experience, they write, also shows that intervening in countries that have these characteristics often does not lead to the growth of democracy.

When it wants to promote democracy in other countries, the US has a number of options, ranging from foreign aid to economic sanctions to military intervention. But how do Americans feel about these different ways of intervening? In new survey research, Abel Escribà-Folch, Lala Muradova, and Toni Rodon find that Americans are more supportive of intervening in autocratic countries which do not hold elections, and are not US allies. But past experience, they write, also shows that intervening in countries that have these characteristics often does not lead to the growth of democracy.

Recent weeks have seen a brutal government-led crackdown on protests in Belarus against the 26-year rule of President Alyaksandr Lukashenko. In response, the foreign ministers of the EU countries have now finally agreed to impose punitive measures on top Belarus officials. The Unites States is following suit, by also considering putting sanctions on seven Belarusian officials who were involved in the recent human rights wrongdoing in the country.

Sanctions, together with military intervention, and foreign aid are the three mostly used foreign policy tools that the US and other countries employ to promote democracy abroad. However, the measures have not been used consistently: while the US has punished some countries following their human rights abuses by either invading them or imposing economic sanctions (e.g. Haiti, Iraq, Cuba), it has abstained from doing so in some other countries despite the presence of similar human rights violence committed by them (e.g. Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Russia).

Foreign policy officials often face an important dilemma: should the United States intervene in another country to promote democracy? If so, how should this be done? Such decisions often spark public controversy. Politicians know that the ability to use certain foreign policy tools might be influenced by Americans’ foreign policy preferences. Yet, we are still largely oblivious as to what shapes these preferences. In new work, we examine what type of autocracies Americans are more likely to support the use of military force or sanctions against and which type of regime Americans are more likely to support giving democracy assistance.

Determining in which countries Americans’ support intervention

We sought to answer these questions by conducting an original survey with a sample of nearly 1,500 voting-age American citizens. Our experiment randomly varied nine different country characteristics and estimated their effects on people’s views on democracy promotion tools. This design allowed us to test the effect of an institutional characteristic (i.e. a regime ruled by a leader with a great deal of personal power – known as ‘personalistic’ – such as Iraq’s former leader, Saddam Hussein or Russian President, Vladimir Putin) and to effectively control for all the other potential characteristics this and other regimes can have.

At the center of our theoretical approach is the expectation that characteristics that make countries that are potential candidates for intervention more different from American democracy (i.e. civilian, popularly elected government and institutional checks and balances), are more likely to be perceived as being an ‘other’ in opposition to the US and thus more threatening to Americans. Such perceptions would lead to the adoption of more coercive foreign policy tools (namely, military intervention and sanctions). On the other hand, citizens may perceive democratic aid as a positive incentive and thus would reward it to those countries which look more legitimate, constrained, and that have ties to the US.

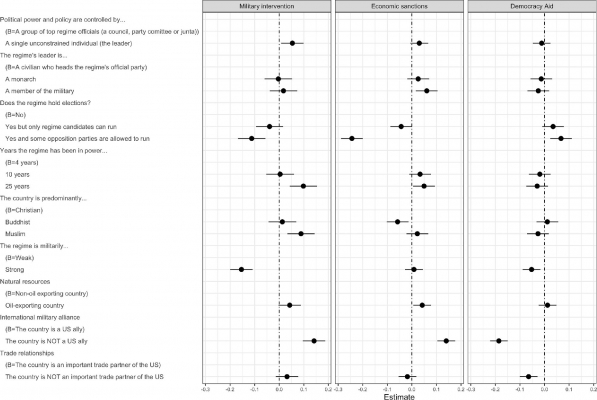

The results of our analyses (Figure 1) show that those in the US are sensitive to electoral competition in the country in question. When the country holds elections with more than one party, Americans are much less likely to support military intervention. In addition to institutional characteristics, the target country’s alliance to the US and military strength are important drivers of public support for war. US respondents are significantly more supportive of a war when the regime is not a US ally; and significantly less supportive of it when the target is militarily strong.

Figure 1 – Support for different types of intervention by country characteristics

Support for democracy aid, on the other hand, is mainly driven by linkages to the US. While economic and strategic linkages with the US and multi-party elections in the target country increase support for democratic assistance, being a predominantly Muslim country and militarily strong dampens it.

Thus, our results show that people are more likely to support harsh measures against personalistic autocratic regimes that do not hold elections and have no ties with the US, such as Iraq or Libya. However, as we know past experience, these measures have often not led to democracy, but to war or state failure. We find that military intervention and economic sanctions are perceived by citizens in our sample as more appropriate in the contexts where, according to the observational evidence from the comparative democratization, is unlikely to advance democratization, namely under-institutionalized, consolidated and personalistic regimes. To illustrate this mismatch, we ran a series of simulations based on estimates from the data.

‘22nd MEU_140812-M-JX299-014‘ by U.S. Naval Forces Central Command/U.S. Fifth Fleet (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

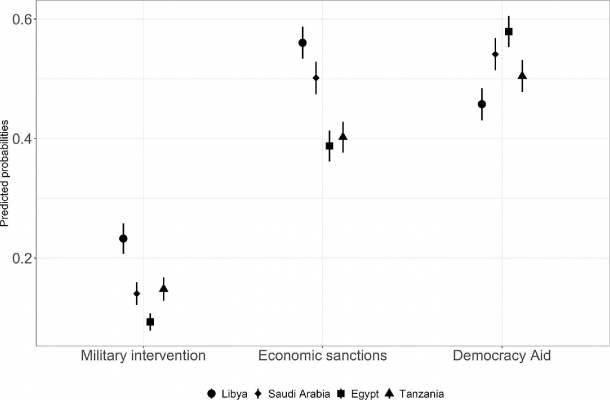

Our results show that the targets that have the characteristics of Libya and Iraq (under Muammar Gaddafi and Saddam Hussein, respectively), that is highly personalistic regimes with little ties to the US, are able to mobilize the highest public support for a military attack and economic sanctions. Both the Libyan and Iraqi regimes saw a series of unsuccessful sanctions imposed by the US government in the past, and when doing so the US government enjoyed public support in 2003 when attacking Iraq and in 2011 when invading Libya. However, none of these punitive measures brought democracy; but rather resulted in civil war and state failure. The cases of Saudi Arabia and Egypt illustrate this point further: despite having certain characteristics that would, in theory, prompt citizens to favor more coercive measures, both are American allies, an important attribute which, on its own, is capable of decreasing individuals’ support for punitive measures against these regimes.

Figure 2 – Predicted probability of support for measures by country

Our findings contribute to our understanding of what underpins much of Americans’ foreign policy preferences and what eventually contributes to the failure or success of foreign policy measures. They also provide evidence that citizens may prefer political candidates who support the adoption of coercive democracy promotion policies or that citizens’ views may be an important driver that shapes politicians’ preferences and discourse on foreign policy. Democratic responsiveness it seems, may conflict with effectiveness.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The Effects of Autocratic Characteristics on Public Opinion toward Democracy Promotion Policies: A Conjoint Analysis’ in Foreign Policy Analysis.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3bMuOyE

About the authors

Abel Escribà-Folch – Universitat Pompeu Fabra

Abel Escribà-Folch – Universitat Pompeu Fabra

Abel Escribà-Folch is an Associate Professor at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra’s Department of Political and Social Sciences and a Senior Research Associate at the Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals. His research interests include comparative authoritarianism, democratization, and democracy promotion.

Lala Muradova – University of Leuven

Lala Muradova – University of Leuven

Lala Muradova is a PhD Researcher at the Centre for Political Science Research of the University of Leuven. Her research interests include political psychology, political behavior, democratic theory and public opinion on foreign policy.

Toni Rodon – Universitat Pompeu Fabra

Toni Rodon – Universitat Pompeu Fabra

Toni Rodon is an Assistant Professor at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra’s Department of Political and Social Sciences. His research interests include electoral participation, political geography, comparative politics, and historical political economy.