Before the Civil War, the politics and economy of the Southern US were dominated by those who practiced immoral – but at the time legally permissible – forced enslavement. In new research, Luna Bellani, Anselm Hager, and Stephan Maurer find that the power of enslavers continued following the end of the Civil War. By examining a database of Texas legislators from 1860 to 1900, they determine that by 1900, about half of all lawmakers still came from families which had held people in slavery.

Before the Civil War, the politics and economy of the Southern US were dominated by those who practiced immoral – but at the time legally permissible – forced enslavement. In new research, Luna Bellani, Anselm Hager, and Stephan Maurer find that the power of enslavers continued following the end of the Civil War. By examining a database of Texas legislators from 1860 to 1900, they determine that by 1900, about half of all lawmakers still came from families which had held people in slavery.

The economy of the US South before the Civil War was largely dependent on enslaved people who cultivated cotton and other cash crops. It is well known that the then legally permissible practice of immoral forced enslavement has had long-lasting economic, political, and social consequences, which are clearly visible in 2020. For example, in regions shaped by slavery, whites continue to express colder feelings towards Blacks, and turnout of Black voters is lower in elections. The dominant elite in the South before the Civil War were the wealthy landowners who held people in slavery, the so-called “planter class”. Their influence in politics before the war can best be illustrated by highlighting that of the 15 presidents before Abraham Lincoln, eight held people as slaves while in office.

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, and the Union victory in the Civil War finally brought the end of slavery in North America. Despite abolishing slavery, the Civil War did not, in fact, end the influence of the former enslavers. Recent research shows that nearly half of the richest 5 percent of property owners in the 1870 South were already among the richest 10 percent in 1860. Former enslavers kept control over their land, and as result also stayed politically influential. This persistence in “de facto power” in turn allowed them to block economic reforms, disenfranchise Black voters, and restrict the mobility of workers. But just how politically influential were those who had held people in slavery before the Civil War after the end of the conflict?

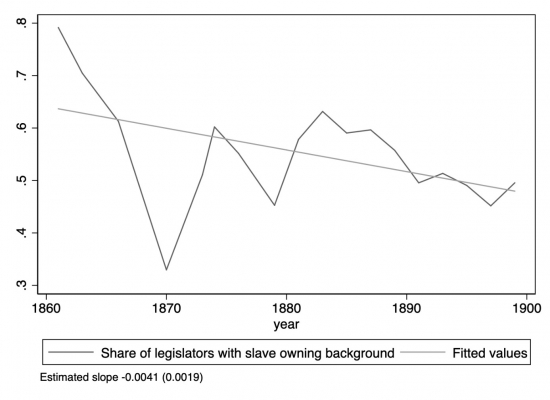

In new research, we set out to answer this question. Using Texas as a case study, we created a database of all members of the Texan Senate and House of Representatives from 1860 to 1900, which we then linked to historical census records prior to their election. We then followed these legislators and (if need be) their ancestors until the 1860 census (the last one to record the incidence of slavery and the identity of enslavers). Doing so allows us to calculate the share of legislators from 1860 to 1900 who came from a family that held people as slaves. Figure 1 below shows the share of lawmakers who were enslavers over time. During the American Civil War, the vast majority of Texan legislators came from a family which had held people as property. This number drops significantly during the era of Congressional Reconstruction (1869). However, by 1872 the share is already back to around 60 percent and it remains at this level for the following decades. Even by 1900 around half of all legislators still come from families which had been enslavers.

Figure 1 – Share of Texan legislators 1860-1900 that came from families that had held people as slaves in 1860

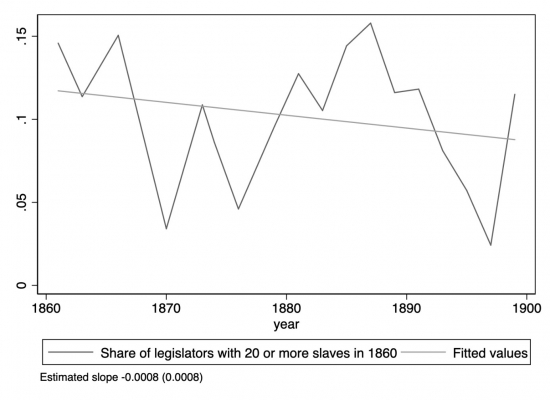

Figure 2 shows the same graph, but focusing on the wealthiest of the wealthiest, the so-called “planter class” (defined as people who had claimed 20 or more people as property). In 1860, only around three percent of all Texan families belonged to this group. Yet, before the Civil War, more than 10 percent of all legislators came from the group of families who had held more than 20 people in slavery. Again there is a sharp drop during Congressional Reconstruction, followed by a swift rebound and an even more stable pattern. By 1900, the share of legislators who were members of the families of the wealthiest of the former agrarian enslavers is essentially at the same level as in 1860.

“Capitol of Texas in Austin, from the General Government and State Capitol Buildings series (N14) for Allen & Ginter Cigarettes Brands” is Public Domain.

Figure 2 – Share of Texan legislators 1860-1900 that came from families that had held more than 20 people as slaves in 1860

How does the background of legislators who came from families who had been enslavers impact politics? Examining the characteristics of these families, we find that those who had held people as property had different occupations prior to getting elected, being more likely to work in agriculture. Politically, legislators from enslaving families also were more likely to be conservative (leaning toward the Democrats). This is consistent with the fact that the Democratic Party in the South after the Civil War represented the interests of the landed elite, and indicates that former enslavers, on average, were more conservative than other legislators. Importantly, these differences along party membership and occupation also hold after statistically controlling for legislators’ 1860 wealth levels. Thus, the differences we find are not simply due to the fact that enslavers were richer.

- This article summarises “The Long Shadow of Slavery: The Persistence of Slave Owners in Southern Law-making”, by Luna Bellani, Anselm Hager, and Stephan Maurer, CEP Discussion Paper No. 1714.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, or of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/31DxLxT

About the authors

Luna Bellani – University of Konstanz

Luna Bellani – University of Konstanz

Luna Bellani is Research Group Leader and Principal Investigator at the Cluster of Excellence “The Politics of Inequality” at the University of Konstanz, a Research Affiliate at IZA in Bonn and at the Dondena Centre for Research on Social Dynamics and Public Policy at Bocconi University.

Anselm Hager – Humboldt-Universität

Anselm Hager – Humboldt-Universität

Anselm Hager is Assistant Professor of international politics at Humboldt-Universität in Berlin.

Stephan Maurer – University of Konstanz

Stephan Maurer – University of Konstanz

Stephan Maurer is Assistant Professor of economics at the University of Konstanz and an Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance.