The US presidential election on 3 November will be watched closely in Europe. Drawing on recent survey evidence, Davide Angelucci, Lorenzo De Sio, Morris P. Fiorina and Mark N. Franklin illuminate the challenge facing Donald Trump in his bid for re-election. There are currently no divisive issues on which Trump stands to win more support from independents and Democrats than he stands to lose from his own support-base, while on issues for which goals are widely shared, Trump lacks credibility compared to Joe Biden.

As the 2020 US presidential election campaign draws to a close (and with most polls reporting a 10-point Biden lead in popular vote intentions), Donald Trump is focused on values, not issues; character, not policies. Some Republican strategists despair at Trump’s preference for enthusing his base rather than reaching out to independents. Some commentators tell us this is “what Trump enjoys doing.” But perhaps he has no choice. Data from an original survey we ran on a US sample of 1,550 respondents between 28 September and 5 October suggests that there may in fact not be any issues that Trump could use to reach beyond his base.

Candidates usually rely on high-yield issues, but…

The data we collected are part of a larger international ICCP project, which has already studied general elections in six West European countries. The project is grounded on issue yield theory: the idea that, in an age when campaigns no longer play on ideological differences, parties and candidates construct their strategies by leveraging their electorally most favourable issue goals. These are goals that combine within-party unanimity, broad support in the general public, and strong party/leader credibility. The problem for Trump in 2020 is that, according to our data, any issues he tries to exploit during the remainder of this campaign are at least as likely to boost support for Biden as for himself. Biden, by contrast, appears much better situated.

The data (1): Joe Biden enjoys more electoral support on most of his high-yield issues

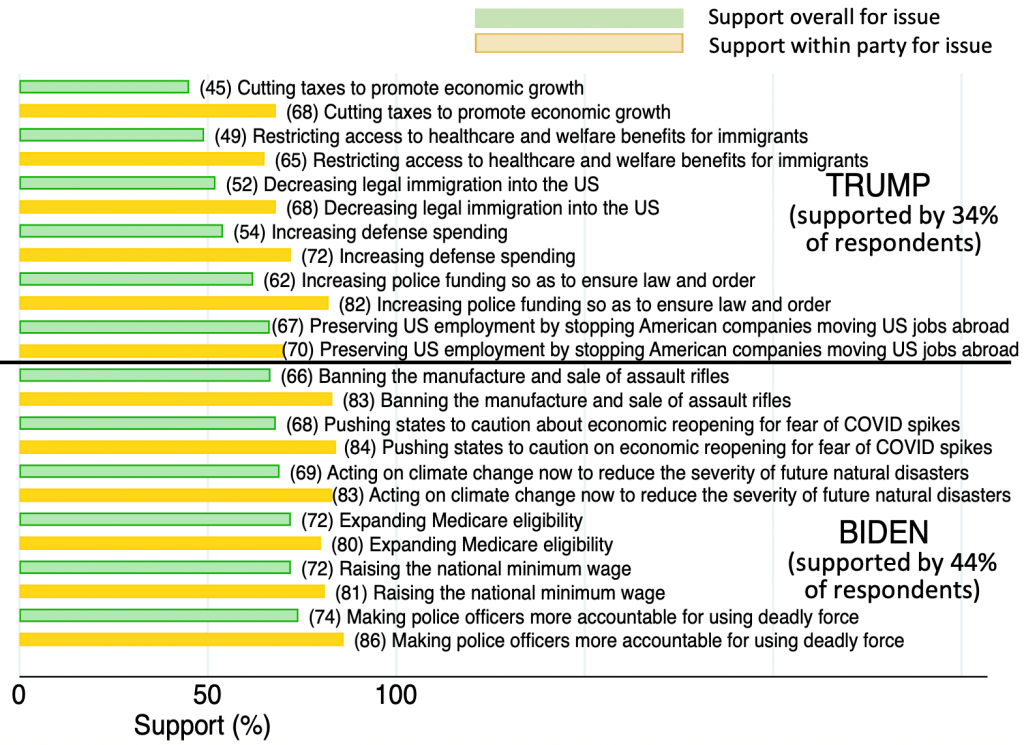

In our survey, we asked potential voters about 30 issues (some related to goals widely shared across the US electorate – like reducing unemployment – some “divisive” issues that involve rival goals – like enacting gun control). When applied to divisive goals, issue yield theory suggests that candidates should stress goals on which their supporters agree and which, at the same time, are strongly supported within the electorate as a whole.

In Figure 1, a longer yellow bar suggests greater support from within the candidate’s base while a longer green bar suggests greater support for an issue outside the candidate’s base. Issues are ordered approximately by issue-favorability for Trump and show a clear divide between the two candidates. Trump stands to gain much less than Biden from an issue-based strategy, since overall support (green bars) for Trump’s issues does not match overall support (also green bars) for Biden’s issues. Moreover, support within the president’s party for these issues is generally lower for Trump than for Biden (Trump’s yellow bars are generally shorter than Biden’s yellow bars).

Figure 1 – Overall issue-support versus issue-support within each party, by candidate

Note: Compiled by the authors.

By stressing any of “his” issues, Trump stands to gain rather little, while risking some loss of his existing support. Biden seems better served by issues that are more widely supported and on which his supporters are more united.

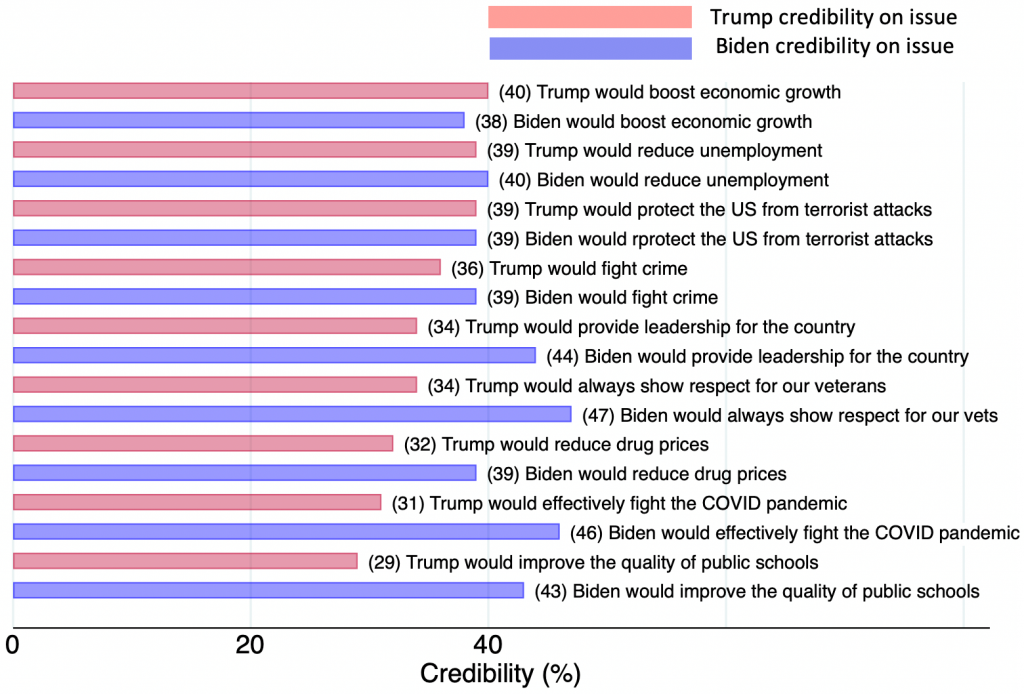

The data (2): Donald Trump has no significant credibility advantage on any issue

What about shared goals? Figure 2 shows an even bleaker picture for Trump when we look at goals that are favoured by supporters of both candidates. This is because, with shared goals, a new consideration comes into play: that of credibility. Almost everyone would like to see higher economic growth, but candidates can be more or less credible for achieving this.

In Figure 2 (for space reasons limited to Trump’s best issues) we see that the incumbent President suffers a significant credibility disadvantage. Again, in this chart, longer bars are better; but this time the bars are coloured according to the candidate concerned, with a pair of bars for each issue again ordered by issue-favourability for Trump.

Figure 2 – Credibility for each candidate, by issue

Note: Compiled by the authors.

Only on his top three issues do we see Trump in a statistical tie with Biden. These three issues (economic growth, unemployment and protection from terrorists) are the issues on which Biden has least credibility but, even on these issues, Biden’s credibility still matches Trump’s. Ironically, Trump’s signature issues (to cut immigration and put the US first) have now become issues on which Trump has so little credibility that none of them even appear in this list of his best issues (Trump’s credibility on his signature issues currently sits below 25%).

Notice that many of Biden’s best issues (such as his stance on health care) do not appear in the chart because they are so unfavourable to Trump. Most notably, Biden’s best issue focuses on a “Black Lives Matter” goal of holding police officers accountable for the use of deadly force. That goal is supported by 86% of Biden supporters and has 74% support in the country.

There are no real issue resources for Trump

According to issue yield theory, the key resource for a party or candidate lies in emphasising issues on which he/she enjoys a competitive advantage, hoping this will lead public opinion to shift in favour of him/her. In trying to decide which issues to emphasise, Trump faces two major problems. One is a lack of divisive issues on which, by stressing them, he clearly stands to gain more in switchers from independents and Democrats than he stands to lose by defections from his own existing support-base. More importantly, on issues for which the goals are widely shared, Trump lacks credibility compared to Biden.

With this configuration of public opinion, no issue-based strategy seems likely to produce for Trump a clear advantage in the remaining days of the campaign. This might well explain why we see him trying out new issues in the hope of finding one that catches fire, even while focusing on non-issue strategies like impugning Biden’s integrity and fitness for the job.

- Note: The authors would like to thank Pippa Norris of Harvard University for help with the formulation of the argument presented in this article.

- Featured image credit: Don Sniegowski (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

- This article first appeared at the LSE’s EUROPP blog.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3eg6x5l

About the authors

Davide Angelucci – University of Siena

Davide Angelucci – University of Siena

Davide Angelucci is a PhD student at the University of Siena and Research Fellow at CISE, LUISS – Guido Carli. His research interests focus on European politics, political behaviour and political participation. He has recently worked on the politicisation of European foreign and security policy. He is currently working on youth and political inequalities in Europe.

Lorenzo De Sio – LUISS Guido Carli University, Rome

Lorenzo De Sio – LUISS Guido Carli University, Rome

Lorenzo De Sio is Professor of Political Science at the LUISS Guido Carli University, Rome, where he teaches several courses at all levels. He is the director of the CISE research centre (Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali), and of the Master’s Programme in Governo, Amministrazione e Politica (GAP).

Morris P. Fiorina – Hoover Institution

Morris P. Fiorina is the Wendt Family Professor of Political Science and a Senior Fellow of the Hoover Institution. He received an undergraduate degree from Allegheny College and a PhD from the University of Rochester, and taught at Caltech and Harvard before joining Stanford in 1998. He has written widely on American politics, with special emphasis on the study of representation, public opinion and elections.

Mark Franklin – European University Institute

Mark Franklin – European University Institute

Mark Franklin was the inaugural Stein Rokkan Professor of Comparative Politics at the European University Institute (EUI) until his retirement in 2011. He remained for several years a Director of the European Union Democracy Observatory at the EUI’s Robert Schuman Center for Advanced Studies. He is still Professor Emeritus at Trinity College Connecticut.