The past year has marked a century since women were granted the right to vote in the US with the Nineteenth Amendment. But writes, Mona Morgan-Collins, in the wake of securing the vote, the suffragists and their successors continued to work to forge greater representation for women through defining women’s issues and informing politicians about them, and by mobilizing and informing women voters.

The past year has marked a century since women were granted the right to vote in the US with the Nineteenth Amendment. But writes, Mona Morgan-Collins, in the wake of securing the vote, the suffragists and their successors continued to work to forge greater representation for women through defining women’s issues and informing politicians about them, and by mobilizing and informing women voters.

This year marks the end of the suffrage centenary of the Nineteenth Amendment which secured the right to vote for women in the US after years of campaigning. And while it was good to be reminded of the suffragists’ immense power that helped to secure the most women the vote – the numerically `largest’ single suffrage reform in US history – it’s also important that we remember that suffragists did much more than this. They also helped to forge the pathway to women’s representation.

The suffrage movement brought together various women’s groups – the feminists, the temperance activists, even the more conservative women’s clubs. Whatever their policy goals, the diverse women’s organizations fighting for women’s suffrage had one thing in common: gaining the vote was a prime means to advance their agenda. It’s hard to disagree with this idea: one can hardly be represented without suffrage. And while it seems sensible to perceive women’s suffrage as a necessary condition for women’s representation, it is not a sufficient one.

Gaining the vote was just the beginning

When most women finally got the vote with the Nineteenth Amendment – Black women’s’ right to vote was not effectively secured until the Voting Rights Act some 45 years later – they continued to face a multitude of barriers to voting. As the first heroic women marched to the ballot box, women’s primary roles in the home continued to be socially expected and heavily institutionalized through marriage bars on employment, gender pay gaps for the same work or gendered curricula at schools. It therefore seems hardly surprising that turnout among newly enfranchised women significantly lagged behind men’s. The anti-suffragist voice echoes in the background: We told you, women were not interested in the vote.

In the years which followed the success of the Nineteenth Amendment, the lack of politicians’ interests in disenfranchised women provided another de facto barrier to women voters. Being excluded from formal politics, early women voters had fewer opportunities to establish voting habits, partisan identifications or to feed their preferences into party programmes. And what exactly did newly enfranchised women want anyways? The differences of women across class and ethnicity was as stark as it is today. It therefore seems hardly surprising that, on average, newly enfranchised women voted pretty much for the same parties as men. The anti-suffragist voice again echoes in the background: We told you, women can be represented by their husbands.

How suffragist increased women’s representation

If women were much less likely to vote than men, and those who voted did so similarly to men, then how could suffrage deliver on its promise to deliver women’s’ policy agenda?

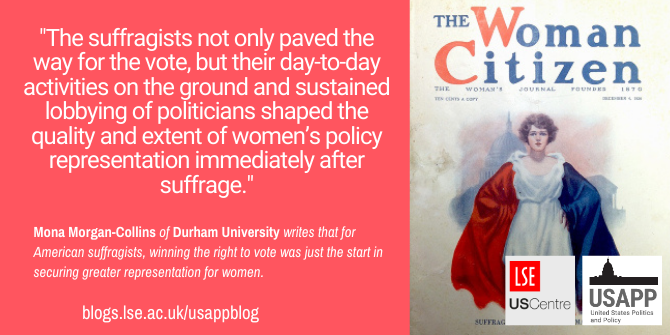

The answer, I suggest, lies in the suffragists and their successor organizations. The suffragists not only paved the way for the vote, but their day-to-day activities on the ground and sustained lobbying of politicians shaped the quality and extent of women’s policy representation immediately after suffrage. Any group that seeks representation of shared interests needs to develop group consciousness of such interests, vote in sufficient numbers, be sufficiently informed about politicians’ positions on shared interests, be prepared to vote on shared interests, and demand politicians to address those interests. The suffragists played a significant role in each of these five steps, effectively easing the realization of women’s substantive representation after winning the vote.

-

The suffragists defined women’s issues

Women’s organizations fighting for suffrage had a long history of advocating social reform, most commonly to protect women and children. The wide array of issues advocated by suffragists included military and maternal benefits, minimum wage, food regulation, equal pay, child labour regulation, improvement of working conditions and prohibition. The National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) collected information on bills that they deemed of importance to women, and issued pamphlets such as `What have women done with the vote.’ Such activities effectively defined the scope of women’s agenda of the day and helped to raise group consciousness of shared interests. But racism within NAWSA, as well as the organizations’ hesitance to include immigrant and working-class women, excluded minority women’s perspectives, and coined the `women’s agenda’ as a version of white, native-born, middle-class progressivism.

Image credit: The Woman Citizen, Dec. 4, 1920. Jean Thompson Woman’s Suffrage Movement Collection, 1871-2005 (MS 971), Part 1, Folio 3. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois History and Lincoln Collections.

-

The suffragists directly mobilized women voters

Suffragists were well aware of the barriers to voting newly enfranchised women faced and the importance of women taking advantage of their newly gained right to vote. The most immediate barrier was the need to register to vote in time – a wholly new task for most women. The suffragists were hardly the only organized group directly mobilizing newly enfranchised women, but their efforts to register women enhanced their turnout.

-

The suffragists informed women voters

Suffragists aimed to reach out to voters frequently, sometimes as much as once a month, and to distribute educational pamphlets and books. A surge of citizenship classes organized by suffragists before the 1920 election aimed to equip newly enfranchised women with substantive information about politics. Some classes ran talks for weeks, others focused on specific topics such as `Problems my community faces’, or covered ‘The Woman Voter’s Manual’, a textbook of American democratic institutions and party platforms.

-

The suffragists enabled women to coordinate at the polls

Suffragists monitored the legislative activity of state representatives and organized state-wide demonstrations against conservative legislation. They were more likely to run negative campaigns against conservative incumbents than positive campaigns endorsing progressive candidates. While suffragists did not directly instruct newly enfranchised women to vote for or against a specific candidate or a party, such activities enabled newly enfranchised women to identify candidates that did not support the suffragists’ broader `women’ policy agenda.

-

The suffragists informed politicians about women’s issues

Women’s groups fighting for suffrage and their successor organizations vehemently lobbied Congress. In the first two Congresses after the ratification of the suffrage amendment, suffragists’ directly supported eight bills, including the landmark Sheppard-Towner Act which provided federal funding for maternity and child care, and the Child Labour Amendment that paved the way for the regulation of child labour. In contrast, the organizationally much weaker anti-suffragist women lobbied only (against) these two bills.

With the conservative turn to `normalcy’ after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, the power of women’s organizations weakened. The National League of Women Voters’ electoral strategy of mass mobilization and on-the-ground activities was replaced with what was primarily a lobbying effort. Not much later, several earlier achievements were undermined – The Sheppard Towner Act failed to be renewed and expired in 1929, and the Child Amendment was never ratified by states. Nevertheless, these legislative accomplishments set a framework for regulation of child labour and maternity welfare of the 1930s. Without the suffragists, granting women the vote would have improved women’s de jure political equality, but may have brought little policy change. The suffragists achieved much more than just `the vote’.

- This article is based on Mona Morgan-Collins’s research, The Electoral Impact of Newly Enfranchised Groups: The Case of Women’s Suffrage in the United States in The Journal of Politics, and the ESRC project, ‘From Suffrage To Representation: Women, Suffragists and Politicians upon Enfranchisement in the U.S., U.K, Norway and Chile’.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3kSerp0

About the author

Mona Morgan-Collins – Durham University

Mona Morgan-Collins – Durham University

Mona Morgan-Collins is an Assistant Professor in Quantitative Comparative Politics at Durham University. Her primary research interests are in historical political science with substantive focus on suffrage politics. Her work on women’s suffrage has appeared in the Journal of Politics, received APSA best paper award, and is funded by a UK Research Council (ESRC) and British Academy (BA).