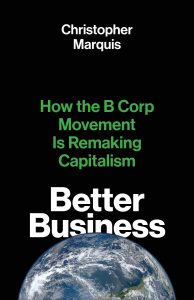

In Better Business: How the B Corp Movement is Remaking Capitalism, Christopher Marquis offers a new study of the history of the B Corp movement as well as its goals, international expansion and its struggles, arguing that it has the potential to redefine capitalism based on principles of accountability, performance, standards and transparency. Marquis’s access to the movement and ability to write organisational history make this book a fantastic read, finds Johannes Lenhard.

If you are interested in this book, you can watch a video of the author Christopher Marquis discussing the B Corp movement, social impact and impact investing as part of an LSE student event organised by the Marshall Institute and recorded on 3 March 2021.

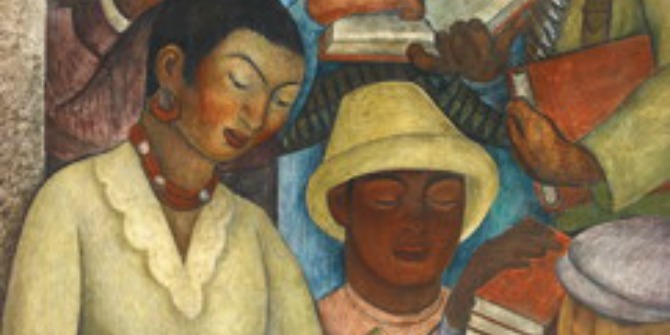

Better Business: How the B Corp Movement is Remaking Capitalism. Christopher Marquis. Yale University Press. 2020.

Doing business better – one B Corp at a time

Doing business better – one B Corp at a time

What do Unilever US, Patagonia and the Guardian Media Group have in common? They are certified B Corporations or ‘B Corps’. To date, over 3,700 companies from 74 countries have made the same step and have become certified by B Lab, the organisation behind B Corp which has been on a journey to bring purpose and profit in business together since 2006. Better Business, a fantastic new volume by Christopher Marquis, is shedding light on the movement, its history and goals, the international expansion and also its struggles. At a time when business leaders at large – from the World Economic Forum to the Business Roundtable – have announced the need to rethink the economy to focus on all stakeholders in a more sustainable economy, shedding light on concrete steps in this direction is of dire need. Marquis, Professor at Cornell Business School, in fact believes that the B Corp movement has the potential to ‘redefin[e] capitalism’ (11). Is he right?

What is at the core of the movement, which started with three friends at Stanford University in 2006, is simple: the triple bottom line of people, planet and profit. While what some call ‘blind neoliberal market belief’ shareholder primacy –that is, the idea that a corporation only exists for the benefits of its shareholders – has dominated over the last decades, B Corp presents an alternative. Marquis helps us to debunk a number of ‘sticky myths’ related to shareholder primacy to conclude that this alternative is indeed needed and viable. For instance, standard assessment of corporate performance (such as by rating agencies) forgets about externalities, such as pollution; these are real costs but are not taken into account in profit calculations so far, including at the national level in measures such as GDP (see also Diane Coyle, 2020). The B Corp answer: creating a brand and movement towards sustainability based on principles of accountability, performance, standards and transparency. The goal: foster good business involving entrepreneurs, investors and thought leaders.

The first – and still most important – tool to enable this movement and the spread of the underlying values (and to ensure them) is the B Impact Assessment (BIA). This consists of a standardised ‘audit’ of the company with a rigorous questionnaire (repeated every two years, documented and visible to the public) which also includes ‘incorporating a social mission into the legal foundations’ of the company (8). It considers five key areas of a company (governance, workers, customers, community and environment); in order to be certified as a B Corp, an 80 out of 200-point bar needs to be reached.

The big ambition of B Lab also includes changing the law to allow companies to establish a distinct corporate entity which has the focus on social and shareholder value built into its statutes; this is deemed important to expand what is widely understood as the company’s fiduciary duty to include stakeholders beyond the shareholders. The ‘benefit corporation’ as a legal form is indeed slowly expanding in the US, from state to state, and also internationally (see Chapter Four), helping to write the B Corp movement even more strongly into literal law.

Marquis further traces the different strands of how the movement and the group of B Corps and community builders have developed over the last fifteen years and his fantastic access and apparent ability to write ‘organisational history’ well really make the book a fantastic read. We learn about how the movement is impacting the investment landscape (with focus on impact investors in Chapter Five investing in B Corps) and how it has been attracting more and more international followers, particularly in Latin America, the UK and, more recently, Europe (see Chapters Seven and Eight). Marquis particularly lauds B Lab’s integration with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (200) and B Lab’s ongoing effort to extend into the realm of big corporate (looking at the examples of Danone and Unilever in detail in Chapter Ten). This is really where a turning and tipping point lies when it comes to ‘redefining capitalism’: ‘how can the B Lab team devise a system that works for large companies’ (206)? A specific internal team (the Multinationals and Public Markets Advisory Committee (MPMAC)) is tasked with this important mission; so far, the process has proven to be ‘significantly more difficult and rigorous for big companies’ (211). Is this where things are getting complicated?

Indeed, some questions remain for me – but mostly about the movement itself rather than Marquis’s coverage of it. Already reading about the loss of early B Corp supporters Etsy, the Honest Company and Warby Parker along their growth journey made me worry: if some committed early adopters drop off around possible risks and uncertainties of ‘legal and compliance issues’, how can you ensure that far less committed corporates ‘convert’? Considering big multinationals and the arduous process they have to go through, the question becomes even more pressing: is this worthwhile at the moment, given that consumer interest is growing but not at all mainstream (as outlined in Chapter Eleven)? Is this really going to affect capitalism at large?

And then the second part of the tension: while some might complain and worry about the (continuous) certification being too labour-intensive and rigid, others are concerned about greenwashing. Throughout the volume, Marquis is acutely aware of this issue associated with earlier movements around corporate social responsibility (CSR) and impact investing (6, 37, 104). In the beginning of the B Corp assessment, the actual checks were not necessarily in place (see page 104: less than 10 per cent of companies were fulfilling reporting duties). Has this changed drastically? Are the companies being held accountable? This is crucial if the B Corp movement is really going to drive any change in practice rather than just narrative. We really need to see what Marquis calls ‘intrinsic good’ (impact as part of the business model) rather than just ‘compensatory good’ (where the business model might even be extractive but you ‘offset’ your damages with philanthropy or CSR activities (40)), and B Corp has the potential to push strongly in this direction.

I believe that Marquis hits the nail on the head very early in the book when it comes to the main challenge for B Lab’s ambition: ‘the status quo is still protected by the old guard, men and women who do not welcome change’ (13). He convinces the reader that the B Corp movement is strong, expanding and ambitious enough to attack this ‘wall of nay-sayers’. But we are also assuming the continuation of a world that is awash with cash and investment – what happens to big corporates, who are already hard to convince, in the next crisis? I have one answer: we need (quantitative) research to show that B Corps perform better financially, that indeed not having the B Corp certification (or a similar kind of impact assessment) means disregarding your fiduciary duty. Then, firms will have to change – and I will be able to share Marquis’s hopeful view that the movement will spread, affecting all corporations, small and large, widely supported by international organisations.

- This article originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

- Image Credit: Photo by Samson on Unsplash.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3bgduDk

About the reviewer

Johannes Lenhard – Max Planck Cambridge Centre for Ethics, the Economy and Social Change

Johannes Lenhard is the Centre Coordinator of the Max Planck Cambridge Centre for Ethics, the Economy and Social Change (Max Cam). While his doctoral research was focused on the home making practices of people sleeping rough on the streets of Paris, he is currently working on a new project on the ethics of venture capital investors in Berlin, London and San Francisco. Find his twitter at @JFLenhard.