US counterterrorism officials continue to grapple with the issue of lone actor terrorism. However, the extent to which these individuals are more dangerous than group-affiliated terrorists is unclear. In new research, Noah Turner, Steven Chermak, and Joshua Freilich investigate the severity of lone actor terrorist attacks compared to those of other terrorists. They find that lone actors do commit more severe attacks than other terrorists, particularly when both fatalities and injuries are considered.

US counterterrorism officials continue to grapple with the issue of lone actor terrorism. However, the extent to which these individuals are more dangerous than group-affiliated terrorists is unclear. In new research, Noah Turner, Steven Chermak, and Joshua Freilich investigate the severity of lone actor terrorist attacks compared to those of other terrorists. They find that lone actors do commit more severe attacks than other terrorists, particularly when both fatalities and injuries are considered.

Lone-actor terrorism

Earlier this month the Biden administration published its first national strategy to tackle domestic terrorism. While the new strategy comes in the wake of the group terror attack on the US Capitol on January 6th, it also cited examples of lone terrorism, such as the 2017 gun attack on a Congressional baseball practice session which injured four, and the 2019 El Paso Walmart shooting where a single gunman killed 23 people and injured 23 others.

The threat of such “lone actor” terrorists has become a focal point for United States counterterrorism policy in recent years. Described as “especially dangerous,” “difficult to detect,” and an “enigma,” lone actors present conceptual and pragmatic challenges for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners alike. On a conceptual basis, the phenomenon of lone-actor terrorism is often difficult to define, as some suggest that no-one can act entirely alone and such actors always maintain some connections to others or receive support from a broader movement. Pragmatically, however, lone actors rarely communicate their plans with others, rendering frequently used counterterrorism strategies, such as informants and/or infiltration by undercover officers, ineffective. With that said, and though the lone actor may be a unique type of terrorist, are they necessarily more dangerous than other terrorists?

Intending to Kill

While some research suggests that lone-actor terrorists are more lethal in their attacks than group-affiliated terrorists, others claim group-affiliated actors pose a greater threat due to their access to resources and training. In these comparisons, though, the actors’ intentions are often not considered. Indeed, not every terrorist commits their attack(s) with the intention of killing people. In fact, the overwhelming majority of terrorist attacks do not kill anyone. There are even some groups and ideological movements that explicitly try to avoid killing or harming people in their attacks.

Alternatively, other movements may justify violence against civilians more freely, considering all people in a certain collectivity, civilian or combatant, as viable targets. These movements often attack so-called “soft” targets, or areas with low security and high civilian casualty potential, to inflict as much harm possible. Logically, terrorists who justify killing in their attacks will always be more lethal than terrorists that do not. As a result, when comparing the lethality of lone actor and group-affiliated terrorist attacks, it is important to ensure that all actors were perpetrating their attacks with the intention to kill.

The Deadliest Terrorist?

We drew a sample of 230 homicide incidents from the US Extremist Crime Database to compare the severity of lone actor terrorist attacks to three other types of terrorists: individuals acting with others without any clear group boundaries, individuals affiliated with an informal terrorist group, and individuals acting under the direction of a formalized terrorist group. Examining only homicide incidents ensured that all included attacks were committed with the purpose of killing people, allowing us to investigate the question: When controlling for the intention to kill, do lone actor terrorists perpetrate more severe attacks than other terrorists?

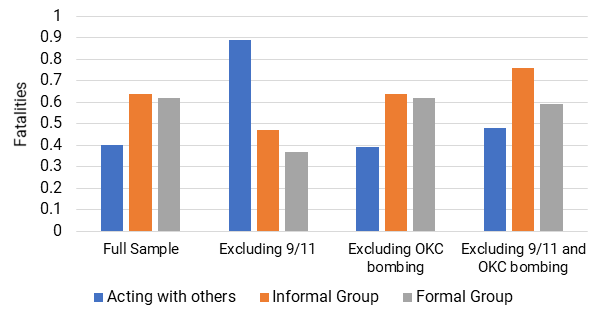

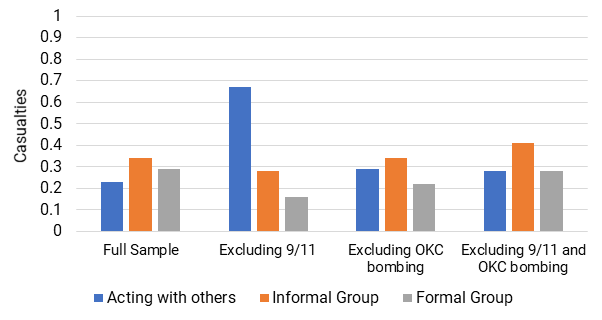

Our analysis considered two violent attack outcomes: fatalities and casualties. Fatalities relates only to the number of deaths occurring as a result of a terrorist incident, whereas casualties includes deaths and injuries in an attack. It is worth noting that we controlled for other factors in our analysis, including whether the attack was a suicide mission, the number of perpetrators involved, type of weapon used, ideological motivation, and the mental health status of the perpetrator. We also accounted for the potential influence of outlier cases, such as the September 11th attacks and the Oklahoma City Bombing, by conducting four independent analyses: analysis with the full sample, one with the 9/11 events excluded, one with the Oklahoma City Bombing excluded, and one with both outlier events excluded.

“Terrorism definition” (CC BY-SA 2.0) by Jagz Mario

In terms of fatalities alone, lone actors were slightly deadlier in their attacks than other terrorists. Figure 1 presents the incident rate ratios (IRR) for fatalities. The IRR essentially tells us how many fatalities other terrorists commit for every 1 fatality caused by a lone actor. For example, in the full sample analysis, those acting with others caused .40 fatalities, and those acting as part of informal or formal groups caused just over .60 fatalities for every 1 fatality caused by a lone actor. Though lone actors were consistently more lethal than other terrorists, these differences were marginal in most comparisons.

Figure 1 – Number of Fatalities Per One Lone Actor Fatality

When casualties were considered as the outcome of interest, the comparison between lone actors and other terrorists was more meaningful. Figure 2 displays the IRRs for the same four samples of terrorist incidents with casualties as the dependent variable. In these analyses, the increased severity of lone actor terrorist attacks is much more visible. Now, in the full sample, those acting with others produce slightly more than .20 casualties for every 1 lone-actor casualty. Similarly, as opposed to the .60 fatalities per 1 lone-actor fatality in Figure 1, informal and formal group actors only caused roughly .30 casualties per 1 lone actor casualty. Clearly, when both deaths and injuries are considered as the metric for attack severity, lone actors are significantly more consequential in their attacks.

Figure 2 – Number of Casualties Per One Lone Actor Casualty

As a whole, this juxtaposition between outcomes tells a complicated, yet informative story. When all actors are intending to kill, those who act alone may not necessarily kill more than other terrorists, but they may be more harmful and injurious in their attacks.

Countering lone-actor terrorism

Effectively estimating the threat of the lone actor is important to guiding policy decisions. Above all, our findings emphasize the need to scrutinize existing counterterrorism policies in their ability to detect and prevent lone-actor attacks. The traditional strategies for thwarting terrorist plots largely consist of intercepting communications between plotters and utilizing undercover officers and informants to obtain information. While these tactics may be effective for terrorists who are involved with groups, the very nature of lone-actor terrorism flies in the face of such strategies. Some scholars have even suggested that those who seek to engage in terrorism in the US prefer to work alone simply because they fear that involving someone in their plans may jeopardize the success of the plot.

However, many lone actors discuss their violent intentions with bystanders, including family, friends, or random strangers. As a result, the focus in recent years has shifted towards soliciting information directly from the public, with programs such as the Nationwide Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR) Initiative (NSI) establishing a system for gathering, analyzing, and investigating tips from the community. Programs like the NSI which use the general public as a resource for identifying suspicious behaviors may be useful in detecting and thwarting lone actor plots, but more research is needed to determine their effectiveness, especially for the online context. Nonetheless, policymakers should continue to utilize our increasingly robust understanding of lone actor terrorism to propose counterterrorism policies that are tailored to the nature of this threat.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘An Empirical Examination on the Severity of Lone Actor Terrorist Attacks’, in Crime & Delinquency.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3qnMx6W

About the authors

Noah Turner – Michigan State University

Noah Turner – Michigan State University

Noah Turner is a doctoral student in the School of Criminal Justice at Michigan State University. He conducts research in the areas of terrorism, radicalization, crime prevention, and public policy. His most recent work has been published in academic journals such as Crime & Delinquency and Social Science Computer Review.

Steven Chermak – Michigan State University

Steven Chermak – Michigan State University

Steven Chermak is a professor in the School of Criminal Justice at Michigan State University. He studies rare violent events, such as terrorism and school shootings. His research has been funded by DHS and NIJ, and recent publications have appeared in Terrorism and Political Violence, Criminology & Public Policy, and Justice Quarterly.

Joshua Freilich – John Jay College

Joshua Freilich – John Jay College

Joshua D. Freilich is a professor in the Criminal Justice Department and the Criminal Justice PhD program at John Jay College. His research has been funded by DHS and NIJ and focuses on the causes of and responses to bias crimes, terrorism, cyber-terrorism, and targeted mass violence; open-source research methods and measurement issues; and criminology theory, especially situational crime prevention.