The past four years have seen vast wildfires in California which have burned millions of acres of land and killed over 100 people. In new research, Iris Hui and Bruce Cain look at how wildfires and their effects influence whether Californians support efforts to adapt to them. They find that, unless they have experienced wildfires close to them, most Californians think that wildfire adaptation is an individual’s responsibility. They also find that, compared to Democrats, Republicans are much less concerned about the harmful smoke wildfires produce.

The past four years have seen vast wildfires in California which have burned millions of acres of land and killed over 100 people. In new research, Iris Hui and Bruce Cain look at how wildfires and their effects influence whether Californians support efforts to adapt to them. They find that, unless they have experienced wildfires close to them, most Californians think that wildfire adaptation is an individual’s responsibility. They also find that, compared to Democrats, Republicans are much less concerned about the harmful smoke wildfires produce.

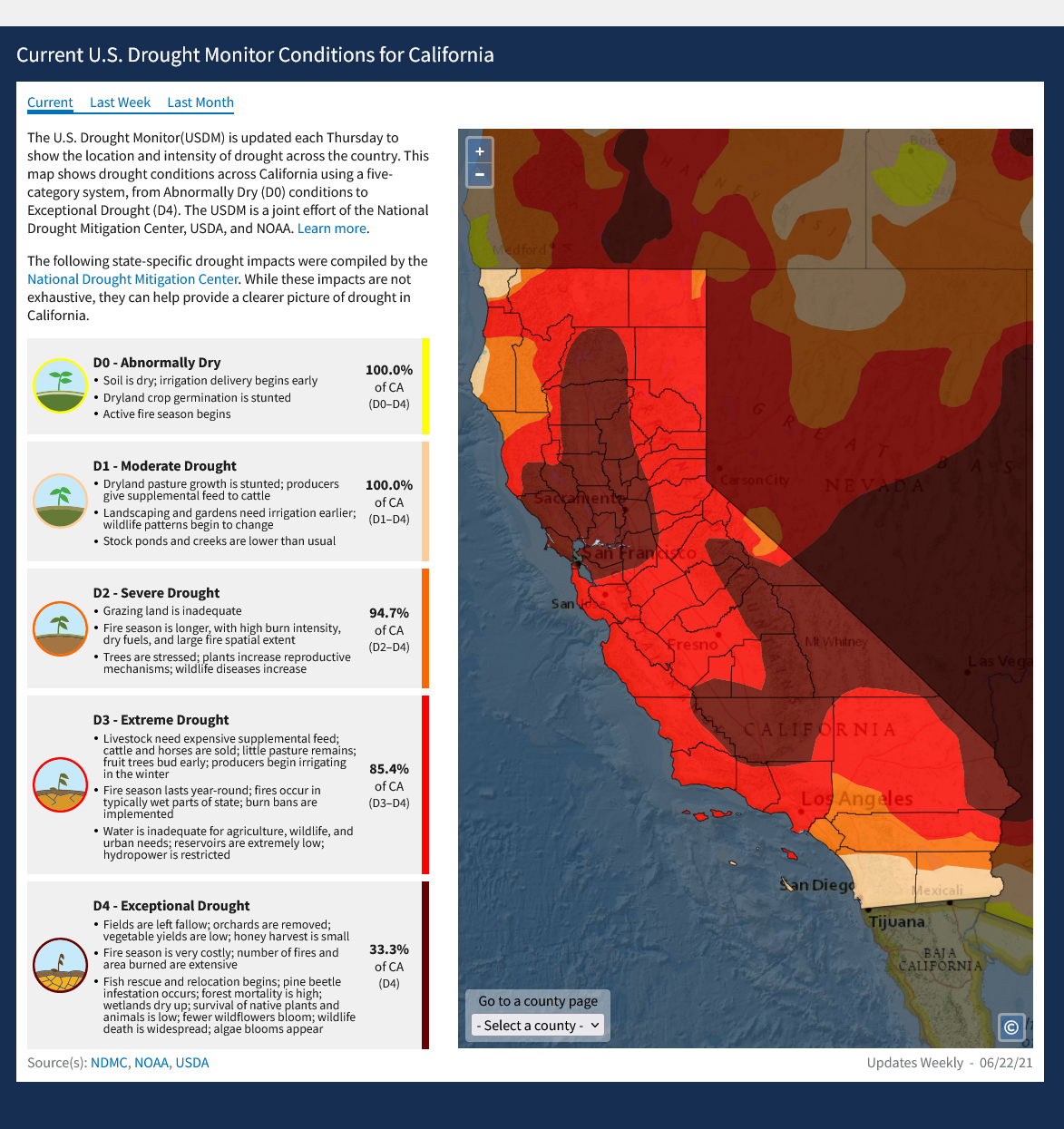

In recent years, wildfires have ravaged the Western American landscape with greater intensity and frequency. California has been especially hard hit. According to CALFire statistics, in 2018 alone, nearly 8,000 California wildfire incidents burned almost two million acres of land, destroyed over 24,000 structures, and claimed the lives of at least 100 people. In 2020, the number of incidents increased to over 9,600, with more than four million acres of land burned and over 30 fatalities. And now in 2021, as Figure 1 shows, about one-third of the state is currently enduring an “exceptional drought” and over 85 percent is under “extreme drought” conditions. The current dry spell is already outpacing the devastating 2012-2016 drought, creating the conditions for another severe wildfire season that could smash previous records in terms of casualties and economic damages.

Figure 1

Source: https://www.drought.gov/states/california

Wildfire experience and willingness for government response

Will these horrific wildfire experiences increase the public’s willingness to support government funding for resilience measures? Previous work has shown that American voters are more inclined to reward politicians for enacting relief measures after a catastrophic event rather than for putting in place preventive policies that would minimize the damage of future natural catastrophes. In addition, rising partisan polarization and persistent Republican skepticism about climate change have increased the difficulty of marshalling support for funding preventive measures. But could the experience of more frequent and more dangerous wildfires alter this pattern of short-sighted thinking?

Many studies have explored whether and how extreme weather experiences like hurricanes, wildfires, flooding can shift public attitudes about the causes and effects of climate change with very mixed results so far. There have been fewer studies to date of whether personal experiences shape public attitudes toward climate adaptation policies. In new research, we use individual-level survey data combined with geocoded information about a respondent’s proximity to wildfire events and exposure to wildfire smoke to assess whether respondents’ experiences with those events increased their support for wildfire adaptation policies.

Wildfires pose two distinct dangers. First, there is the danger of the flames destroying lives and property, especially of those who live within or next to the so-called wildland-urban interface areas. Secondly, there is the danger and multiple days of exposure to wildfire smoke containing significant concentrations of PM2.5 and other hazardous materials that can cause both acute respiratory problems resulting in hospitalizations and long-term changes to the body’s immune systems.

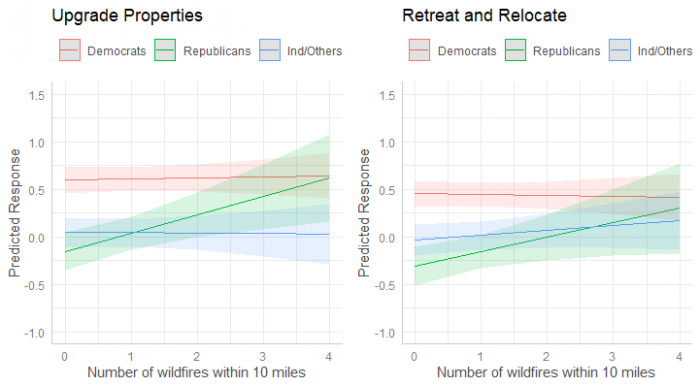

In general, our data show that a majority of Californians oppose the imposition of restrictive government measures (e.g. requiring property upgrades or more restrictive zoning) and prefer that the decision to take adaptive steps remain a matter of personal choice. Moreover, party affiliation matters: Republicans are more opposed than Democrats to spending public funds to subsidize resilience measures. When testing whether proximity to a wildfire or inhaling wildfire smoke alters the willingness to use public funds to subsidize protective steps, we find that proximity to wildfires does lessen Republican opposition to using public funds to encourage homeowners to upgrade their properties or relocate to safer places in order to protect themselves from wildfires. In Figure 2 below, the upward sloping line indicate Republican support for the measure as the respondent experiences more fires within 10 miles of where they reside. There is little or no change to Democrats and Independents support.

Figure 2 – Response to wildfire adaptation measures by party affiliation and proximity to wildfires

Note: The dependent variables are ordinal in nature (-2=strongly disagree; 2=strongly agree). OLS with survey weights are applied. As the number of wildfires increased, partisan gaps on attitudes toward using public fund to upgrade properties or buy wildfire insurance decreased.

However, exposure to wildfire smoke either has no effect or slightly increases the partisan divide between Democrats and Republicans on using public money to encourage homeowners to take resilience measures. This is consistent with the fact that while the danger from flames is indisputable, the hazard of smoke is perceived differently across party lines: Republicans are much less inclined to believe that exposure to wildfire smoke is harmful to an individual’s health. In short, while the danger from the flames is an easily comprehended hazard, it mainly changes the opinion of Republicans who live in close proximity to the fire, which is a small fraction of the California electorate. On the other hand, even though wildfire smoke is dangerous and is spread by the winds across a wider swath of citizens, its harmful health effects are less well known and appreciated by the public.

“Destruction, hope, and resilience” (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) by PeterThoeny

Wildfire risk and cost to society

There are several important implications from these findings. To begin with, the widespread belief in California that people should be allowed to make their location and resilience decisions regardless of wildfire risk is highly problematic. The problem is compounded by the fact Californians also prefer making people safe in place rather than moving them to safer places. These individually chosen risks result in higher socialized costs, such as the expenses and dangers of firefighting, the insurance losses that drive up rates, caring for displaced populations, liability costs due to downed utility power lines parking fires, and so on.

Experiencing nearby wildfire at least inclines some Republicans to be more supportive of using public funds to upgrade their properties to be resilient in place (e.g. home hardening, defensible space, etc.) and to enable people who want to leave and rebuild elsewhere to do so. But the number of residents who live next to or within wildland-urban interface areas is not sufficiently big to have a large impact on public opinion. Of course, if the costs to fighting fires and paying for their clean up continue to grow, the socialized costs of individual freedoms will become more apparent over time and could change the prevailing perspective that decisions about where to live.

Wildfire smoke is in many ways comparable in danger to second-hand smoke from tobacco. Politically it could potentially have a more immediate impact and at a scale that would change many people’s minds about the seriousness of the drought and wildfire problems associated with global warming. However, we do not find that exposure to wildfire smoke had a significant positive effect on willingness to use public funds for wildfire resilience measures in 2018-19 and in some cases even diminishes support for public funding of certain resilience measures. And the partisan gap does not change: Republicans were less likely to agree that the smoke is harmful or that people need to invest money to protect themselves from that smoke.

Will concerns about wildfires change as they get worse?

What, then, will it take for personal wildfire experiences to produce greater partisan agreement on wildfire adaptation policies? Clearly, the continued expansion into wildland-urban interface areas and the effects of a warming climate will increase the number of evacuations and personal experiences with wildfires. Perhaps, the expense of fighting these fires will alter perceptions about requiring and publicly subsidizing stricter preventive measures. Or perhaps, the wildfire concern of those who live in wildland-urban interface will be bundled with those who suffer from more extreme heat, water scarcity or sea level rise to form an extreme weather coalition that log rolls each other’s concerns into a winning coalition that can adopt a serious program of extreme weather resilience.

Wildfire smoke has the reach but not the perceived hazard level, particularly among Republicans. This might be lessened with better information outreach, but the problem of motivated reasoning will likely undercut such efforts. As with the rising costs of fighting and recovering from wildfires, the expense of dealing with the health costs associated wildfire smoke may eventually increase support for wildfire adaptation measures in the future. In the meantime, the partisan gap on climate change resilience will likely persist.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Baptism by Wildfire? Wildfire Experiences and Public Support for Wildfire Adaptation Policies’ in American Politics Research

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3AhYkIC

About the authors

Iris Hui – Stanford University

Iris Hui – Stanford University

Iris Hui has obtained her PhD in Political Science from the University of California, Berkeley. She is a senior researcher at the Bill Lane Center for the American West, Stanford University. Her research interests include American politics, geography, political behavior, environmental politics and governance.

Bruce E. Cain – Stanford University

Bruce E. Cain – Stanford University

Bruce E. Cain is a professor of Political Science at Stanford University and director of the Bill Lane Center for the American West. His fields of interest include American politics, political regulation, democratic theory, and state and local government. He has written extensively on elections, legislative representation, California politics, redistricting, and political regulation.