By creating processes which allow for public participation, governments can better involve citizens in their decision-making. Iuliia Shybalkina looks at the use of one type of public participation – participatory budgeting – across six New York City council districts. She finds that the incentives council members faced had a large influence on how their districts invested in the participatory budgeting process, leading to often very different processes in different districts.

By creating processes which allow for public participation, governments can better involve citizens in their decision-making. Iuliia Shybalkina looks at the use of one type of public participation – participatory budgeting – across six New York City council districts. She finds that the incentives council members faced had a large influence on how their districts invested in the participatory budgeting process, leading to often very different processes in different districts.

Public participation in government is an umbrella term covering a wide range of processes that allow people to contribute to public decision-making. With very few caveats, elaborate public participation infrastructure has long been touted as an important aspect of governing which has real benefits to individuals, communities, and government institutions. Yet, in reality, the use of public participation remains spotty in local governments around the United States. Scholars have tried to explain this variation by highlighting the role of public officials’ personal and professional qualities, the size and diversity of the community, civic traditions, community conflict, pressure from stakeholders, political transformations, and electoral competition. However, we still really don’t know why some local governments are eager to engage people in solving community problems and others are not so much.

To find out why this might be the case, I examined differences in participatory budgeting (PB) and some probable reasons for these differences in six New York City (NYC) council districts. PB transfers the authority to propose and make decisions on publicly funded capital projects from elected representatives to the public and has been spreading very rapidly and extensively in the US and globally. Each of NYC 51 council members decides whether they are interested in using PB to allocate their several million dollars of discretionary funds and what the PB process will look like. I observed PB processes and conducted interviews in six different NYC districts in 2017-2018. In addition, I obtained further information on districts from traditional and social media and statistical sources.

Different approaches to participatory budgeting

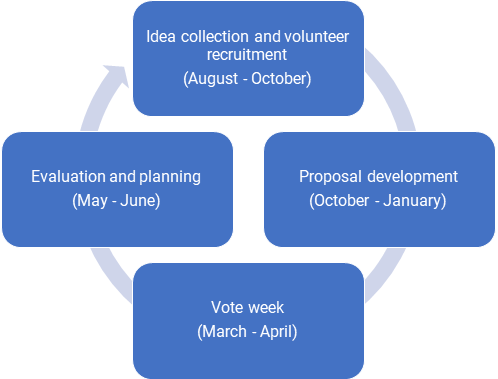

I was amazed at how different the six PB processes were, even though they were in the same city and modeled on the same rulebook. In its ideal form, as shown in Figure 1, the process – which includes brainstorming project ideas, developing detailed project proposals, and voting – incorporates extensive outreach and opportunities for education and deliberation. Some districts adopted all the procedures recommended by PB advocates and implemented them to the fullest extent possible. However, other districts opted for a very abridged version of PB. For example, two out of six districts did not recruit volunteer residents that would narrow down ideas and select proposals that meet community needs. Instead, district offices themselves decided which projects would appear on the ballot.

Figure 1 – Standard PB Timeline

Source: PBNYC Cycle 9 Rulebook.

Council members’ incentives mattered a great deal for how much effort districts invested in the participatory budgeting (PB) process. It is, of course, difficult to understand the incentives that may motivate people, and incentives change all the time. Still, several types of situations appeared to encourage districts to prioritize PB. For example, some council members used participatory budgeting (PB) to highlight their likenesses to some circles (e.g., new political guard) and differences from others (e.g., old political guard). For other council members, PB was a tool to appeal to progressive residents. Yet other council members hoped that PB would help them recover from allegations of inefficiency and lack of transparency. Unfortunately, when council members did not face any strong incentives, PB activities tended to be poor.

“Participatory Budgeting NYC materials” (CC BY 2.0) by Daniel-Latorre

Not only politicians are driven by incentives, but so are civil society organizations (CSOs) such as community services centers, neighborhood associations, parent–teacher groups, and park groups. Because of eligibility requirements, PB can only fund a narrow set of small capital projects (technology in schools, playgrounds, pedestrian safety islands, etc.). PB is also known as a “working-within-the-system” rather than a “protesting against the system” form of participation. So, CSOs interested in such projects and in good working relationships with the council member – e.g., community centers, neighborhood associations, parent-teacher groups, and park groups – became the backbone of PB. In contrast, CSOs that are more interested in expense than capital funding (to rent a space, etc.) preferred to attend a workshop on how to apply for expense funds. CSOs that disapprove of the council member opted for community forums, protests, and marches.

While environmental incentives played a prominent role in how PB looked, public officials’ internal convictions and experiences were also contributing factors, which confirm some of the previous studies on this subject. For instance, the district where council members experienced homelessness as children involved shelters for homeless veterans and women and a Girl Scouts troop of homeless girls in PB events. To give another example, the community affairs specialist in charge of PB in one of the districts decided to focus PB activities on building trust rather than on specific capital projects. This is because they grew up in the district and believed that the community’s main issue was the distrust between the people and the government.

The potential costs of requiring public participation

The bottom line is that, because incentives will always vary, we cannot expect all local governments to direct their resources towards extensive public participation. So then, if a society believes that public participation is valuable, this society may need to consider external interventions to improve the standard of public participation in all local governments. One option is to centralize participation; for example, in NYC, PB can be run at the city- instead of the council district-level. Another option is to require specific public participation standards from all local governments. Unfortunately, both options have drawbacks – losing the benefits of decentralization and imposing unfunded mandates, respectively. More research on the value of participation (including its different forms) and the effectiveness of interventions to promote participation would be helpful to policymakers.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Toward a positive theory of public participation in government: Variations in New York City’s participatory budgeting’ in Public Administration.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/367El1p

About the author

Iuliia Shybalkina – University of Kentucky

Iuliia Shybalkina – University of Kentucky

Iuliia Shybalkina is an Assistant Professor at the Martin School of Public Policy and Administration at the University of Kentucky (Lexington, KY). She studies processes that allow people to influence public financial decision-making at the local level, including participatory budgeting in cities and schools, community development, and public comments. She also researches various local public finance topics, including property and sales taxes, intergovernmental aid, and post-employment benefits.