In the US juvenile justice system, the time that young people wait between arrest or referral to the final outcome of their case is largely unregulated. In new research, Abigail Novak and Elizabeth Hartsell examine the effects of case processing time on youth re-arrest rates. They find that context is important: females and low-risk youth on diversion, and detained youth with non-felony charges, and detained youth of color were all at greater risk of re-arrest the longer their case took to run its course.

In the US juvenile justice system, the time that young people wait between arrest or referral to the final outcome of their case is largely unregulated. In new research, Abigail Novak and Elizabeth Hartsell examine the effects of case processing time on youth re-arrest rates. They find that context is important: females and low-risk youth on diversion, and detained youth with non-felony charges, and detained youth of color were all at greater risk of re-arrest the longer their case took to run its course.

Unlike defendants in the criminal justice system, young people in the juvenile justice system are not guaranteed the right to a speedy trial. Because of this, case processing time – defined broadly as the time between arrest or referral to the juvenile justice system and the settling of the case – is largely unregulated in the juvenile system. The American Bar Association (ABA) and some states provide case processing time standards for juvenile courts, with some of these standards considering case factors such as whether or not the youth was detained when giving case processing time recommendations. Though intended to provide guidance for the courts, these standards rely on the largely untested assumption that shorter case processing times are better for all kids, regardless of case or youth characteristics.

Existing research provides little insight into the potential effects of case processing time on re-arrest, and whether or not these effects differ according to youth and/or case characteristics. Past research suggests case processing time could impact re-arrest differently based on individual characteristics such as risk level (as determined by risk assessment tools), gender, race, and/or age. It also suggests case processing time could impact re-arrest based on case characteristics such as detention status during case processing, if youth had access to counsel, or if the youth was placed in a diversion program (for example, drug court or teen court). In an effort to better understand the effects of case processing time on re-arrest, we examined whether case processing time was related to re-arrest for justice-involved youth, and whether this relationship differed according to youth and/or case characteristics.

Longer Case Processing Leads to More Re-Arrest

In our analysis of over 100,000 youth who entered the Florida juvenile justice system for the first time between 2012 and 2016 we found that longer case processing times were associated with an increase in re-arrest. Using an approach that allowed us to account for differences in youth and case characteristics, we found the probability of a youth being re-arrested within one year was greater the longer the case took to process. If the case took 15-60 days, the probability of re-arrest was higher than in similar cases that took two weeks or less. If the case took longer than 60 days to process, the probability of re-arrest was even higher.

Case Processing Time Does Not Affect All Youth Equally

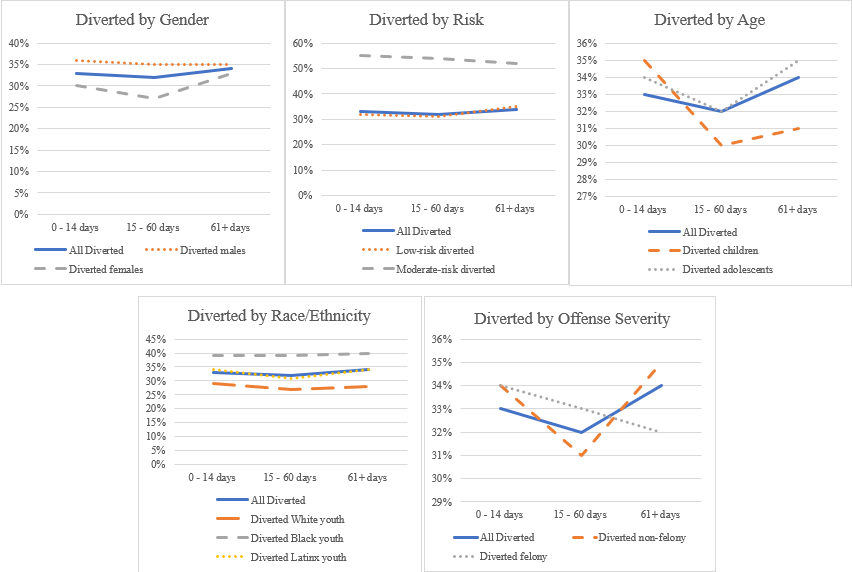

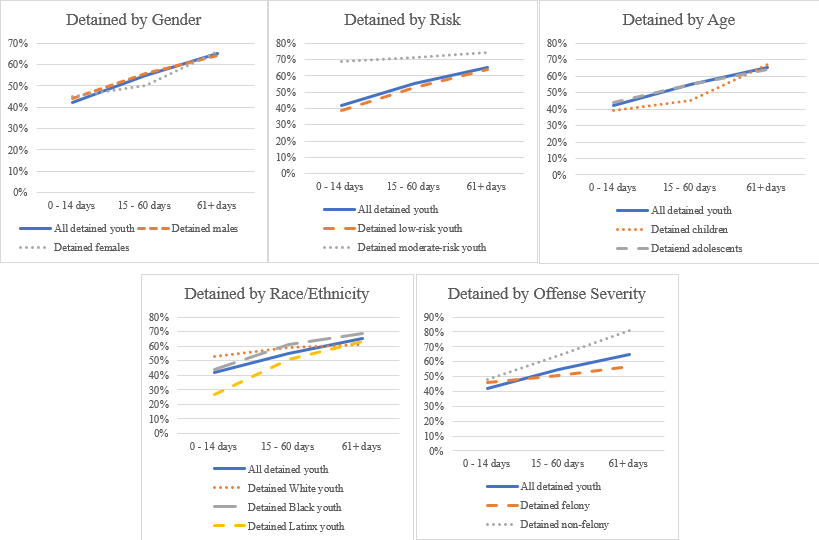

Though generally longer case processing times increase the risk of re-arrest, this relationship does vary according to case context. Longer case processing time increases the chance of re-arrest for some youth but not others, as illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. Specifically, for females and low-risk youth who were diverted, longer case processing time led to increased re-arrest (Figure 1). This suggests the beneficial impacts of diversion program participation may dissipate if lower-risk youth experience longer case processing times. This could be due to the increased time under juvenile court supervision which increases the chances that the youth is re-arrested for committing a technical program violation or a new delinquent behavior.

Longer case processing times were associated with significant increases in re-arrest for detained subgroups including males and females, low-risk youth, youth with non-felony charges, and youth of color, but not white youth (see Figure 2). Given the disproportionate policing and surveillance facing youth of color, longer case processing times may leave the youth vulnerable to excessive monitoring and intervention on the part of the juvenile justice system, ultimately increasing risk of re-arrest.

“Juvenile and Domestic Court, Warrenton,” (CC BY-NC 2.0) by Jason Pier in DC

Figure 1 below shows how longer case processing times were not found to increase re-arrest for all youth. Specifically, case processing time did not impact re-arrest for diverted males, diverted youth charged with a felony offense, and diverted moderate-risk youth. Figure 2 illustrates how case processing time did not impact re-arrest for detained youth charged with a felony offense and detained moderate-risk youth. These findings suggest longer case processing times may not increase the risk of re-arrest among youth who may have more complex or severe cases associated with their referral. It is possible that these youth may present with cases requiring more extensive intervention than other youth. Rather than serving to ensnare, longer case processing times may signal judicial attempts to ensure appropriate, individualized service delivery for these young people.

Figure 1 – Probability of re-arrest by case processing time among diverted subgroups

Figure 2 – Probability of re-arrest by case processing time among detained subgroups

Jurisdictions should consider the contextualized effects of case processing time on re-arrest

Though assumed to be benign in juvenile justice policies, case processing time can impact risk of re-arrest for justice-involved youth. Given the absence of consistent standards regulating case processing times in the juvenile system nation-wide and the lack of resources facing some juvenile courts, understanding the nuanced effects of case processing time is an important task for local and state juvenile justice officials. Because longer case processing times may increase risk of re-arrest, juvenile court officials should be aware of the potential ensnaring effects of longer case processing times for young people.

When looking for youth to prioritize for prompt case resolution, local and state juvenile court officials should consider prioritizing prompt case processing for detained youth, as these youth may be more likely to be re-arrested than non-detained youth as the length of time, they spend involved with the juvenile court system increases. For higher risk diverted youth, such as diverted males, youth who score higher on risk assessments or youth with felony charges, prompt case resolution may be less of a priority, as longer case processing times did not impact re-arrest for these groups.

Understanding the complex effects of case processing time is essential to meeting the needs of youth in the juvenile justice system. System officials must consider how case processing time may function according to youth and case needs to improve youth outcomes and reduce risk of future arrest and justice system involvement for youth.

- This article is based on the paper ‘Does Speed Matter? The Association Between Case Processing Time in Juvenile Court and Rearrest’, in Crime & Delinquency.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/39aUjsW

About the authors

Abigail Novak – University of Mississippi

Abigail Novak – University of Mississippi

Abigail Novak is an assistant professor at the University of Mississippi in the Department of Criminal Justice and Legal Studies. She received her Ph.D. in Criminology, Law and Society at the University of Florida. Her research interests include systems and delinquency, delinquency prevention, early-onset antisocial behavior, and applied quantitative methodologies. Her work has appeared in journals such as Criminal Justice and Behavior, the Journal of School Violence, Crime & Delinquency, Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, and others.

Elizabeth Hartsell – University of Florida

Elizabeth Hartsell – University of Florida

Elizabeth Hartsell is a doctoral student at the University of Florida. Her research interests include problem-solving and alternative courts and treatment programming in the criminal justice system.