From presidential races to local elections, decisions about where politicians send their children to school can attract public attention. But do these choices actually impact how voters cast their ballots? In new research, Leslie K. Finger, Thomas Gift, and Andrew Miner use an original survey experiment to examine how voters view politicians who send their children to public versus private school. They find that voters are more likely support candidates whose children attend public school — an outcome they trace to voters perceiving these candidates as warmer and more committed to public services.

From presidential races to local elections, decisions about where politicians send their children to school can attract public attention. But do these choices actually impact how voters cast their ballots? In new research, Leslie K. Finger, Thomas Gift, and Andrew Miner use an original survey experiment to examine how voters view politicians who send their children to public versus private school. They find that voters are more likely support candidates whose children attend public school — an outcome they trace to voters perceiving these candidates as warmer and more committed to public services.

Schooling choices that politicians make for their children are often in the public eye. For example, the New York Times, while reporting on the Trump family’s decision to send Barron to private school, noted that previous educational choices by politicians over where to send their children to school have “triggered a media circus” and been met with “intense national interest.” On the other side of the partisan aisle, the fact that Elizabeth Warren sent her son to a private school, despite her prominent support of public education, triggered heightened scrutiny and charges of hypocrisy.

This is not just an issue in high-profile, national campaigns. In Wisconsin, a state school superintendent candidate was similarly accused in March this year of “mountain-sized hypocrisy” for sending her children to a religious-run school, even as she railed against school choice. In Michigan, a trustee of a local board of education likened a school board member who did not choose the public-school option “to the CEO of General Motors driving a Toyota.”

Do schooling decisions by politicians affect how voters evaluate them? To examine this question, we fielded an original survey experiment with a diverse, national sample in the US. We asked survey-takers to evaluate two hypothetical candidates for state office, randomly varying whether the candidates had children—and, if so, whether they sent them to public (state-run) or private school. As shown below, we found that respondents were significantly more likely to vote for candidates whose children attended public school.

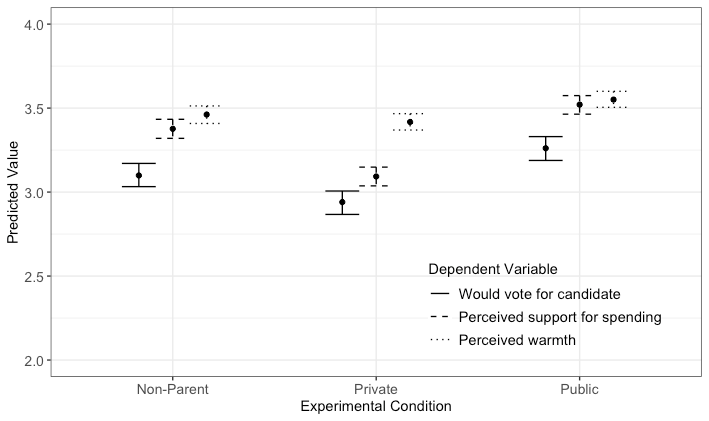

Figure 1 – Predicted Values of Ballot Box Appeal, Perceived Warmth, and Perceived Support for Public Spending

Predicted values range from 1-5. For ballot box appeal, 5 = “Extremely unlikely” to vote for the candidate; for warmth (composite index), 5 = the words “likeable,” “conscientious,” “friendly,” and “caring” describe the candidate “Very well” (see Pedersen et al. (2019)); for support for spending (composite index), 5 = candidate would be “Very likely” to “advocate for more funding for public [schools / anti-poverty programs / transportation / health initiatives].” Dots represent the median predicted value. The displayed results are calculated by simulating predicted values using models that regress each dependent variable on the public school and non-parent conditions, with no controls.

Why do voters prefer public school politicians?

First, we hypothesized that voters prefer politicians who send their children to public school because they see them as “warmer.” In the US, private schools are often perceived as serving the elite, whereas public schools are associated with serving ordinary Americans. This could lead voters to believe that public school politicians are more relatable.

Our data confirmed that respondents considered politicians who sent their children to public school to be overall more likeable, friendly, caring, and conscientious – traits we used as a proxy for warmth. Furthermore, respondents whose own children attended public schools deemed public school candidates particularly warm.

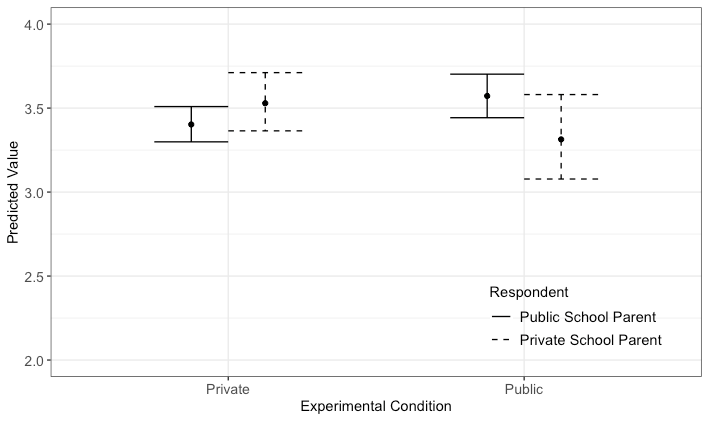

Figure 2 – Predicted Values of Perceived Warmth, by whether the Respondent is a Public or Private School Parent

Predicted values range from 1-5 (composite index). 5 = the words “likeable,” “conscientious,” “friendly,” and “caring” describe the candidate “Very well.” Dots represent the median predicted value. The displayed results are calculated by simulating predicted values using a model that regresses the warmth index on the non-parent and public-school conditions and interacting the public-school condition with whether the respondent sends his or her children to public school, with no controls.

Second, we hypothesized that voters prefer public school politicians because they judge them to be more committed to public services. Given polling showing that large majorities of Americans favor increasing or preserving levels of government spending, candidates who can credibly commit to generously financing public policies might enjoy electoral advantages.

“Around Old Town” (CC BY-NC 2.0) by dr. zaro

Our data confirmed that respondents thought public school politicians would be more supportive of state outlays for education, healthcare, transportation, and welfare programming. Additionally, respondents believed that public school politicians would be especially committed to spending on public education compared to other policy areas.

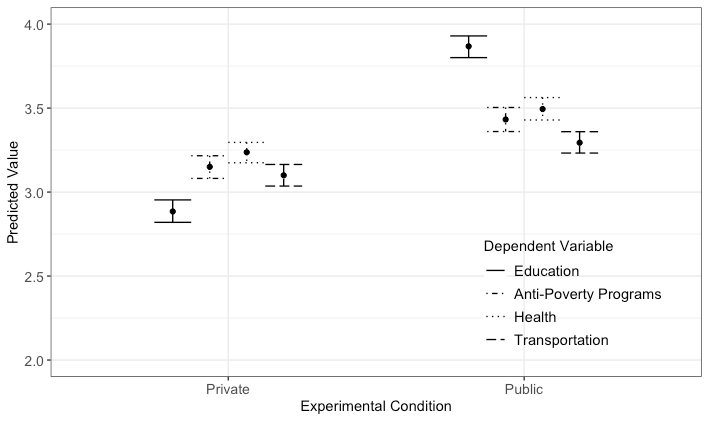

Figure 3 – Predicted Values of Perceived Support for Public Spending, by Policy Area

Predicted values range from 1-5. 5 = candidate would be “Very likely” to “advocate for more funding for public [schools / anti-poverty programs / transportation / health initiatives]. Dots represent the median predicted value. The displayed results are calculated by simulating predicted values using models that regress each dependent variable on the public school and non-parent conditions, with no controls.

Links between Partisanship and Schooling Choice

One potential issue with our analysis is that voters may see schooling choices as predictive of a candidate’s partisanship. For example, Democrats are often seen as more supportive of public education, especially given their opposition to school choice and advocacy for more spending on public schools.

As such, voters might assume that politicians who send their children to public school are Democrats, and either vote for them (or not) accordingly. Our results, however, show that even after controlling for respondents’ political leanings and their perception of the candidate’s partisanship, voters were more likely to support candidates who send their children to public school.

Implications for Campaigns

In addition to adding to an extensive literature on how candidate backgrounds affect voter evaluations, our study offers insight into how an important family choice by politicians can shape their public images.

When politicians emphasize that their children attend public school in campaign messaging, they can expect voters to perceive them as warmer and more committed to public services, translating into greater support at the ballot box. This may, in turn, influence campaign strategy, with candidates drawing attention to this decision (or downplaying a decision to send their children to private school).

Schooling choices are just one of many family decisions that candidates make. Others include choices regarding where to live, religious participation, lifestyle habits, marriage, and whether to have children. Exploring how these and other decisions affect voter perceptions is important to developing a more complete picture of the factors underlying candidate appeal.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘DCPS or Sidwell Friends? How Politician Schooling Choices Affect Voter Evaluations’, in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2Y8K85T

About the authors

Leslie K. Finger – University of North Texas

Leslie K. Finger – University of North Texas

Leslie K. Finger is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of North Texas.

Thomas Gift – UCL

Thomas Gift – UCL

Thomas Gift is Associate Professor of Political Science at UCL, where he is director of the Centre on US Politics (CUSP).

Andrew Miner – Yale Law School

Andrew Miner – Yale Law School

Andrew Miner is a student at Yale Law School.