Abdul Alkalimat discusses his new book, The History of Black Studies, exploring some of the complex and diverse historical origins that led to the emergence of Black Studies in the US as intellectual history, as a social movement and as an academic profession.

October is Black History Month in the UK. LSE’s theme for 2021 is ‘BLACK 365’ and you can explore the events taking place at LSE this month.

Rethinking Black Studies as a Freedom Project

One of the most impactful results of the 1960s Black liberation movement has been the creation of Black Studies as a formal education programme. But Black Studies has been much more than that. My new book, The History of Black Studies (Pluto Press, 2021), offers a comprehensive discussion that clarifies its complex and diverse historical origins.

One of the most impactful results of the 1960s Black liberation movement has been the creation of Black Studies as a formal education programme. But Black Studies has been much more than that. My new book, The History of Black Studies (Pluto Press, 2021), offers a comprehensive discussion that clarifies its complex and diverse historical origins.

First, a definition: ‘This book defines Black Studies as those activities: (1) that study and teach about African Americans and often Africans and other African-descended people; (2) where Black people themselves are the main agents, or protagonists, of the study and learning; (3) that counter racism and contribute to human liberation; (4) that celebrate the Black experience; and (5) that see it as one precious case among many in the universality of the human condition.’

Given this concept of Black Studies, there are three main historical ways to measure and discuss its development: Black Studies as intellectual history; Black Studies as social movement; and Black Studies as academic profession. The main argument is that Black people have been rational about their experience, thinking about what has happened and developing a serious literature and cultural practices. Moreover, Black activists have engaged their community to be involved, and acted with focused agency on the institutions of society for the social change needed to achieve their political and moral objectives.

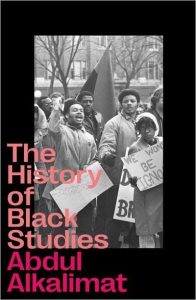

Image Credit: ‘Black studies [poster], April 1969’. 969.100.2 (106), olvwork719165. Harvard University Archives

Black intellectual history combines both academic disciplinary scholarship and community-based research and cultural activism. The first two generations of Black PhDs worked their way through elite graduate programmes, but institutional racism blocked them from being hired in the very institutions they had excelled in. Many of their dissertations laid the foundation for all future research on the Black experience in their respective disciplines. They went on to teach and base their scholarship in the historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). This included such scholars as WEB Du Bois in history, E. Franklin Frazier in sociology and Charles Thompson in education.

In the community great work was done in Black high schools. In addition, community-based institutions were developed such as museums, community centres, publications (newspapers, journals and book publishers) and literary societies. The activists were African Americans as was their audience.

While still based in the community, Black activism created social movements that led the struggle for self-determination on the path to freedom. In each case, and I document six, there were educational programmes that continued the development of Black Studies. The six cases are the following: the Freedom movement for civil rights, the Black Power movement, the Black Arts movement, the New Communist movement, the Black Women’s movement and the Black Student movement.

Each of these movements created a curriculum to raise the consciousness of the community, and as such turned ideas into a material force for change. All subsequent academic scholarship is based on the agenda set by the knowledge production of these social movements.

The main paradigm shift in these social movements was the emergence of Black Power as a slogan that changed everything. The shift was from a focus on being accepted by mainstream gatekeepers to a process of self-affirmation and community-based authenticity. This was also a shift from a more middle-class orientation to the mass base of Black working-class and poor people. The aesthetic pronouncement that ‘Black is beautiful’ became a mental explosion that transformed Black people from being trapped in its oppression into a national celebration of self-affirmation.

The pattern in these social movements was the development of what I call ‘emergent institutions’ that organised education programmes. Some were short-lived and others survived the decades. The Freedom movement initiated what came to be known as ‘Freedom Schools’. This was important in the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, as well as in Northern school boycotts, especially Chicago. In the Black Arts Movement organisations were formed in each form of art by Black Power advocates, including such inclusive organisations as the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) in Chicago.

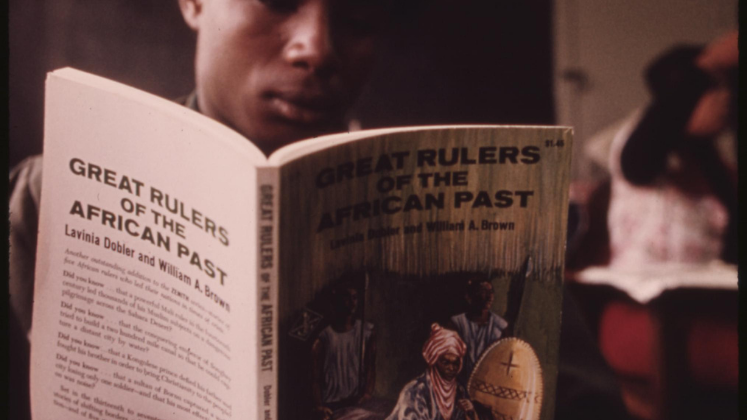

Image Credit: Crop of ‘Black Student In A Black Studies Class In A West Side Chicago Classroom Reading A Book About Great Rulers In Africa’s Past, 10/1973’. Photograph by John H. White licensed by The US National Archives under No Known Copyright Restrictions.

Image Credit: Crop of ‘Black Student In A Black Studies Class In A West Side Chicago Classroom Reading A Book About Great Rulers In Africa’s Past, 10/1973’. Photograph by John H. White licensed by The US National Archives under No Known Copyright Restrictions.

The major challenge for mainstream institutions sprang into focus after the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968. There was more than a five-fold increase of Black students in mainstream colleges. This brought a confrontation between institutional racism and the Black Power consciousness the students brought with them. The institutions were not ready for this challenge: the absence of Black students, faculty and staff was normal, and white experts controlled what was considered legitimate knowledge about Black people, what little there was. Black people upset this by demanding more Black people in all capacities as well as knowledge that made sense to them. They demanded Black Studies. This included affirmative action in hiring, more inclusive enrollment of students and a new curriculum.

Conflict birthed a new innovation. Our conceptual framework of the historical development of Black Studies as an academic profession includes six aspects of development, sometimes chronological and sometimes not: conflict, struggles for consensus, institutionalisation, professionalisation, theoretical developments and the norming of research.

As an academic profession, Black Studies has developed key organisational assets, including professional organisations that establish structures for self-governance. These include The National Council for Black Studies, The Association for the Study of African American Life and History and the African American Intellectual History Society. Each of these organisations have a process of peer-reviewed publications. In addition, over a dozen institutions have developed PhD programmes, the professional degree that legitimates research standards for an academic profession.

There have been latent and manifest ways that Black Studies has functioned in higher education. At the manifest level Black Studies has earned its place as an official terrain of academic scholarship. At the latent level Black Studies remains a resource for Black liberation, both within higher education as well as for all battlefronts utilising the knowledge production of the student movement and other academic resources. Black Studies is academic and political at the same time. It is important to remember that higher education has always served a social and political purpose, just in this case it is a resource for the oppressed and not the oppressors.

The History of Black Studies is a general survey of the historical experience that can usefully be explored in depth. The organisation of the book is also a guide for research, especially to document the history of a specific institution. This historical project is an important part of the transformation of higher education. We have provided a model for this at the University of Illinois.

There are other books that will be well worth your time to explore:

There are other books that will be well worth your time to explore:

For Black Studies as intellectual history: Nathaniel Norment, African American Studies: The Discipline and Its Dimensions and William Banks, Black Intellectuals: Race and Responsibility in American Life.

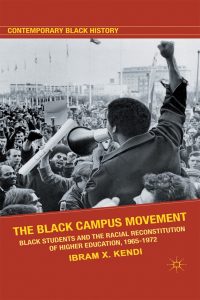

For Black Studies as social movement: Russell Rickford, We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination and Ibram X. Kendi, The Black Campus Movement: Black Students and the Racial Reconstitution of Higher Education 1965-1972.

For Black Studies as academic profession: Martha Biondi, The Black Revolution on Campus and Fabio Rojas, From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement Became an Academic Discipline.

Note: This feature essay gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Thank you to Harvard University Archives for giving permission to use the image of ‘Black Studies [poster], April 1969’. This image should not be re-used with permission of the Archives.

- Banner Image Credit: ‘Black Student In A Black Studies Class In A West Side Chicago Classroom Reading A Book About Great Rulers In Africa’s Past, 10/1973’. Photograph by John H. White licensed by The US National Archives under No Known Copyright Restrictions.

- This article first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2ZGvHY6

About the author

Abdul Alkalimat – University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign)

Professor Abdul Alkalimat (PhD Sociology, University of Chicago) is a veteran scholar-activist in Black Studies. He wrote the first textbook in Black Studies, which is now on display in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. He edits the website on Malcolm X (brothermalcolm.net) and the listserv abdulslist. He is currently Emeritus Professor of African American Studies and Information Science at the University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign). His website is alkalimat.org.