On July 4th, 2026, the United States will celebrate its 250th anniversary. Thomas Cryer looks at the work of the US Semiquincentennial Commission ahead of the anniversary, writing that the planned ‘America250’ celebrations are unconnected, and tend to compartmentalise American history rather than evoking a straightforward national narrative. This disconnectedness, he argues, risks creating a vacuum in which current politicians may push their own partisan values and narratives.

On July 4th, 2026, the United States will celebrate its 250th anniversary. Thomas Cryer looks at the work of the US Semiquincentennial Commission ahead of the anniversary, writing that the planned ‘America250’ celebrations are unconnected, and tend to compartmentalise American history rather than evoking a straightforward national narrative. This disconnectedness, he argues, risks creating a vacuum in which current politicians may push their own partisan values and narratives.

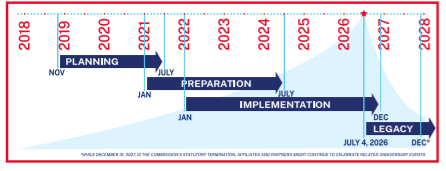

It has been commonly quipped that growing old is not bad when one considers the alternative. Yet America appears to be approaching its 2026 Semiquincentennial, the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, with a policy of reluctance, if not benign neglect. Following the conclusion of the celebration’s “planning” phase this past July, most Americans could still be forgiven for asking ‘Semiquincentennial, what Semiquincentennial?” After all, a survey ran recently by the commemoration’s own planning body found that only 1 percent of Americans had heard about the event.

Semiquincentennial, Sestercentennial, Quarter Millennium or Bicenquinquagenary; even the naming is convoluted, meaning most commemorative content now favours the more readily franchisable America250. 1776, however, has lost little of its political force, particularly within nationalist rhetoric. In 2021 the mere number “1776” adorned numerous flags during the January 6th Capitol riots and has become a slogan in campaigns against critical race theory. Indeed, one of President Trump’s last acts in office was to rekindle calls for “patriotic education” through his own 1776 Commission. All the while, The New York Times’s “1619 Project” has called, to mixed reception, to trace American’s origins before 1776 to 1619 when the first enslaved Africans arrived in colonial Virginia.

Bridging Public and Private Celebrations

H.R. 4875, The United States Semiquincentennial Commission Act of 2016, nonetheless declared that 1776’s events “(1) are of major significance in the development of the national heritage of the United States of individual liberty, representative government, and the attainment of equal and inalienable rights” and “(2) have had a profound influence throughout the world.”

To match the current distaste for ‘made in Washington’ uniformity, this Commission has consciously severed itself from the federal government, serving instead as a bridge between the public and private sectors. Its original board was composed of sixteen private citizens, eight members of Congress and nine (now twelve) non-voting Federal Government officials. The Commission seeks to “plan, encourage, develop and coordinate” a veritable smorgasbord of activities including producing books, pamphlets, films; creating bibliographic and documentary projects; holding conferences, convocations, lectures, or seminars; developing libraries, museums, historical sites or exhibits; re-enacting ceremonies or celebrations and producing coins, medals, certificates of recognition or stamps.

Figure 1 – America 250 Schedule

Source

America250 consequently skews towards compartmentalising American history into rather more benign individual episodes which free local commemorators from addressing ‘big’ and divisive national questions, echoing the US’s comparatively laissez-faire attitude to national memory. Lacking a Ministry of Culture, American commemorations frequently feature flags, re-enactments, “Founders’ Chic” and sporting extravaganzas; favouring ‘patriotism’ over ‘nationalism.’ For those sceptical of unitary visions of America’s past, history frequently appears with a small-h, the history (if not heritage) of individual towns, states, and key figures. To borrow from the social theorist Michael Billig, American nationalism-cum-patriotism is frequently banal, particularly when commercially ‘steered’. Revealingly, Major League Baseball has already scheduled its 2026 All-Star Game for Philadelphia.

The Triumph of Vernacular Memory?

Writing on American memory, the historian John Bodnar argues that the function of public memory is to mediate competing realities expressed by official and vernacular cultural expressions. For Bodnar, 1976’s Bicentennial (the US’ 200th anniversary) saw the victory of vernacular over official memories within this balance, a process catalysed by a thriving identity politics celebrating the particulars of race, class, gender, and sexuality.

2026 shows little indication of reversing this trend towards the intimate and familiar. This January, America250’s Chairman DiLella claimed that it would be “the largest and most inclusive commemoration in American history with the opportunity to produce more than 100,000 national and grassroots programs, attract billions of dollars in resources, and promote tourism for cities and states across the country.”

John Dunlap; text by Thomas Jefferson et al., Public domain, via the Library of Congress.

Yet, the question must be “250 years of what?” Will 2026 celebrate an anti-imperialist revolt or a mass societal revolution, the Declaration of Independence’s signing, or the Revolutionary War’s battles? The American Battlefield Trust’s role as the Commission’s official non-profit partner appears to suggest more of the latter. Yet America250 has generally sought to dilute 1776 within the grander arcs of American history. When interviewed for the Washington Post, its Vice President Keri Potts argued that inclusivity “means staying grounded in 1776, but remembering that there is history before and after 1776 that needs to be told.”

In Washington D.C., for example, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the National Museum of the American Indian, and the Smithsonian Latino Center are collaborating on an exhibition commemorating “the many 1776s” so that “all Americans, no matter where they live, will see themselves in the telling of the American Story.” A 30-second TV spot launched this January showed suffragists parading in 1920s New York, Jesse Owens competing at 1936’s Berlin Olympics, and Orlando, Florida’s 2018’s Pride Parade.

The commemorative geography of the semiquincentennial also reflects this wide-ranging vision. H.R. 4875, earmarked as “leading cities” Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, all classic heritage industry heartthrobs. Yet it also marked Charleston, South Carolina, a city where around one-half of those enslaved arrived in the US which has long been grappling to overcome a whitewashed heritage industry in its campaign to become “America’s Most Historic City.”

The Dangers of Disaggregation

Nevertheless, the danger remains that a more visceral, straightforward reading of American history could easily outmuscle a disaggregated, diluted commemoration lacking the connective tissue of a clear narrative or central theme. History abhors a vacuum. For example, the conservative Heritage Foundation’s 2020 Presidential Essay, penned by the former Republican Speaker for the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich, criticised “the trivialization of the historic uniqueness of the Declaration of Independence” which typified the “pathetic but passionate desire of left-wing academics to recognize and denigrate American exceptionalism.” Social media feeds are already filled with “myth-busting” histories that border upon conspiracy theory, attributing Americans’ present discontents to amoralism, narcissism, and a betrayed national purpose.

In this sense, 2026 will only exacerbate two long-running debates which Trump’s Presidency drastically aggravated. First, America’s past has steadily become as polarized as its present. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences recently noted that “polarized depictions of American history continue to divide us and impede productive civic collaboration.” Recent American Historical Association surveys likewise found that while 70 percent of Democrats believe history should question America’s past, 84 percent of Republicans believe history should celebrate it. White respondents were twice as likely to believe that history currently focuses excessively on racial and ethnic minorities.

Second, the contestation by Republicans of the transition to President Biden undoubtedly worsened disagreements about the Constitution’s institutional legacies. Particularly if America votes Republican in 2024, 2026 may become an opportunistic paean to a starkly originalist reading of the Constitution, celebrating those essential historical values that unify the fusionist consensus of economic libertarians and conservative evangelicals. Within what Jill Lepore calls this “historical fundamentalism” 1776 and its institutional products are “ageless and sacred and to be worshipped.” Equally, Democrats desiring more structural alterations to America’s institutions may seek to utilise 2026’s symbolic leverage to push for the admission of additional states, revamp the electoral college, and/or initiate comprehensive Supreme Court reforms.

America250 itself will likely make a double movement, acknowledging marginalized groups’ struggles whilst rarely specifying what they struggled against. Several thousand well-intentioned sideshows will allow most Americans to identify with something while the central dilemma, that of celebrating the revolutionary beginnings of a national experiment that is only becoming further mired in institutional deadlock, will remain unaddressed. With five years left, the past has rarely appeared this unpredictable.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3FUGoWg

About the author

Thomas Cryer – UCL

Thomas Cryer – UCL

Thomas Cryer is a first-year LAHP-funded PhD Candidate at UCL’s Institute of the Americas. Having received a BA(Hons) in History and an MPhil in US History at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, he is now embarking on a project investigating race, memory, and nationhood in late twentieth-century America through the lens of the life, scholarship, and activism of the historian John Hope Franklin.