Journalists often brand themselves as “storytellers” to signal their reporting expertise. But in new research, Brian Calfano, Jeffrey Blevins and Alexis Straka find that because of the public’s perception of the label, using the “storyteller” brand may actually have negative implications for journalists, especially those who report on politics.

Journalists often brand themselves as “storytellers” to signal their reporting expertise. But in new research, Brian Calfano, Jeffrey Blevins and Alexis Straka find that because of the public’s perception of the label, using the “storyteller” brand may actually have negative implications for journalists, especially those who report on politics.

A common brand journalists use to describe themselves professionally is “storyteller.” Based on Twitter scrapes of journalist profiles, we found hundreds of high-profile reporters and former reporters using the term. The obvious intent behind this professional descriptor is the desire for audiences to perceive “storyteller” as a positive journalistic attribute. Indeed, a charitable interpretation of the “storyteller” brand is that it signals a reporter’s expert crafting of information to increase audience understanding of one’s reportage.

Critics, however, argue that the “storyteller” brand applied to journalists privileges the role of the reporter over the report, encouraging vanity and self-congratulation. But there are potentially far wider implications. If the public is inclined to interpret the “storyteller” brand negatively, then any positive intent by reporters and their media outlets doesn’t matter.

To be sure, the diversity of reporting contexts is broad enough that some reporters may never encounter criticism from associating their professional role with the “storyteller” label. But harder to imagine is that journalists who report on politics or politically charged topics go unscathed when using the term professionally.

By definition, storytellers may not be truth-tellers

The core problem may be linguistic. No matter how journalists and their media employers intend for audiences to perceive the term, the dictionary definition of “storyteller” is mostly (though not totally) the opposite of truthfulness. According to Merriam-Webster, a “storyteller” is defined as a) a relater of anecdotes, b) a reciter of tales (as in a children’s library), c) liar, fibber, d) a writer of stories. Most of that definition is the opposite of what professional journalists would want as a branding attribute. This goes triple for political reporters. After all, the inherent problem with branding oneself as a teller of stories when reporting on politics in the “fake news” era should be blindingly obvious.

To make this case empirically, we fielded an Internet-based survey-embedded experiment on 2,133 US adults featuring an article on local politics that randomly exposed respondents to a one-sentence description that the journalist “describes himself as a storyteller on his LinkedIn page.” Control group subjects did not receive this LinkedIn information—just the politics article. The story in question is political, but generally not partisan: it discussed local zoning ordinances. We then asked respondents whether they perceived 1) story bias, 2) sensationalism, 3) trivialization, 4) fair portrayal, 5) reporter bias.

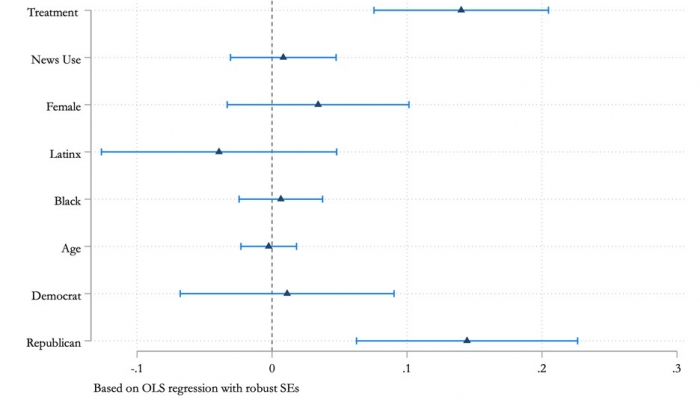

Using question responses to generate an additive bias index score, Figure 1 shows that both those who received the storyteller description and Republican-identifying respondents perceive more overall bias in the story than their control and non-Republican counterparts. That means respondents seeing the “storyteller” label matched to the reporter had a more negative impression of the zoning story (and the reporter).

Figure 1 – Perceived article bias when ‘storyteller’ label is used

How do people perceive ‘storyteller’ journalists?

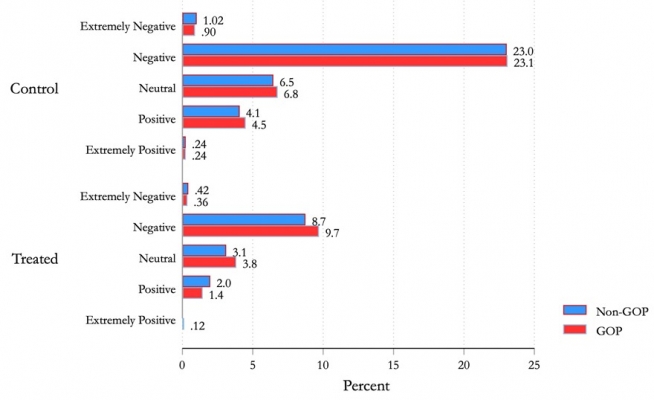

We took our analysis further by asking respondents to provide an open-ended response: “when you see the term ‘storyteller’ used to describe a journalist, what comes to your mind?” (We did not remind treated respondents that the journalist in their version of the article used this label). The percentage of the 1,733 usable open-ended responses were extremely negative (3 percent), negative (64 percent), neutral (20 percent), positive (12 percent), and extremely positive > 1 percent).

Photo by Bernard Hermant on Unsplash

Some of the most frequent words and phrases respondents offered help show the extent to which they did not evaluate the “storyteller” brand positively. For example, a variation of the phrase “made up” (including “makes up” and “make up”) appeared in 264 separate respondent comments. “Fake news” was used 255 times. “Liar” appeared in 239 comments (including 41 times where variations of “made up” appeared and 38 times where respondents used “fake news”). The terms “fictional” and “embellish,” both of which are less harsh in tone, appeared in 197 and 178 respondent comments respectively. By the same token, a small group of respondents did perceive the “storyteller” brand label in the manner its journalist users likely intend. They offered positive sentiments focused almost entirely on the skill involved in telling a compelling story (though these positive perspectives were clearly in the minority).

Figure 2 shows that, given, the large percentage of respondents offering negative sentiment about the “storyteller” brand, neither the storyteller” brand cue nor party identity statistically affected the open-ended response. Both Republican and non-Republican respondents offered negative sentiments with virtually equal frequency, suggesting that the reaction against the journalist use of the “storyteller” brand may be different from Republican skepticism about media more generally.

Figure 2 – Reaction to ‘storyteller’ brand

Our results show that, while “storyteller” is a branding cue journalists employ, the public’s overall perception of the label, and of a journalist’s reporting when that cue is salient, is not positive. Just as importantly, the negative open-ended perceptions respondents offered were essentially the same regardless of party identity.

What journalists, media managers, and academics should take from these findings is that while the “storyteller” brand is popular in journalistic circles, its adoption may end up backfiring in the actual perceptions it creates, even on local and non-partisan political topics. To be sure, public perception is likely variable and context dependent on this subject. Our findings don’t suggest that all journalists should avoid using the “storyteller” brand entirely. But political reporters in the “fake news” era could probably stand some sober consideration of what alternative branding cues work best.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Bad Impressions: How Journalists as “Storytellers” Diminish Public Confidence in Media’ in the Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3M1BVVP

About the authors

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian Calfano is Professor of Political Science and Journalism at the University of Cincinnati. He has 55 peer-reviewed journal articles to his credit and is the co-author of several books, including The American Professor Pundit: Academics in the World of US Political Media. Calfano is also a reporter for Spectrum News 1.

Jeffrey Blevins – University of Cincinnati

Jeffrey Blevins – University of Cincinnati

Jeffrey Layne Blevins is Professor of Journalism at the University of Cincinnati. He has published in a variety of academic journals, including New Media and Society, Journal of Mass Media Ethics, and Television & New Media. He serves as editor of the journal Democratic Communiqué.

Alexis Straka – Numerator

Alexis Straka – Numerator

Alexis Straka holds a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Cincinnati. She works as a research analyst for Numerator, after several years at NielsenIQ. Her research features in academic journals including Political Research Quarterly and Religions.