In recent decades, many governments have attempted to encourage people into work by reducing welfare eligibility. By analyzing the changes in the American Supplemental Security Income program (SSI) policies, Manasi Deshpande and Michael Mueller-Smith find that rather than incentivizing people into employment, removing welfare support instead may push them towards illicit activities to make up for lost income. This increase in criminal activity and subsequent incarceration has large monetary and social costs for society, which effectively cancel out the savings to government from reduced welfare spending.

In recent decades, many governments have attempted to encourage people into work by reducing welfare eligibility. By analyzing the changes in the American Supplemental Security Income program (SSI) policies, Manasi Deshpande and Michael Mueller-Smith find that rather than incentivizing people into employment, removing welfare support instead may push them towards illicit activities to make up for lost income. This increase in criminal activity and subsequent incarceration has large monetary and social costs for society, which effectively cancel out the savings to government from reduced welfare spending.

Over the past few decades, developed countries have seen substantial changes to their social assistance programs. In the United States, the 1996 welfare reform law slashed welfare programs and implemented barriers to enrollment like work requirements and recertification. The austerity measures enacted in Europe during the Great Recession of 2007-09 introduced similar cuts. Cuts to welfare programs have historically been motivated by concerns that these programs can discourage educational achievement and work. Studies on the effect of welfare programs on work have found mixed results—in general, they find that welfare programs do discourage work to some extent, though often they are discouraging work among individuals who would not earn much even in the absence of the program

Our new research looks at the effects of welfare programs on a different type of “work”: criminal activity intended to generate income. Using a natural experiment created by the 1996 welfare reform law, we find that removing young adults from the US Supplemental Security Income program (SSI) increases criminal justice involvement, and especially increases illicit activity intended to generate income. We estimate that removing a young adult from the SSI increases the total number of criminal charges associated with income generation (theft, burglary, robbery, drug distribution, prostitution, and fraud) by 60 percent over the following two decades. This greater incidence of criminal activity leads to a 60 percent increase in the likelihood of a person being incarcerated each year over the same period.

Effects of Supplemental Security Income on crime

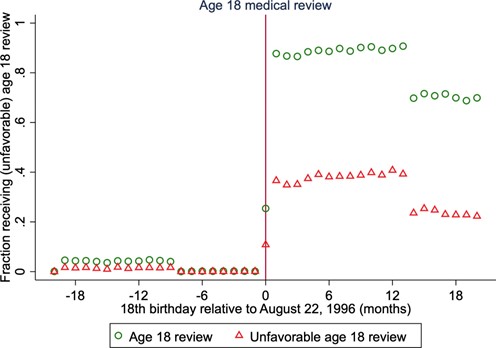

Our work takes advantage of a policy change created by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996, more commonly known as welfare reform. Among its many restrictions on welfare programs, it included a rule that children receiving SSI benefits for a disability had to be reevaluated for SSI under the stricter adult rules when they turned 18 years old. Under the new rule, any child with an 18th birthday after the law’s enactment—August 22, 1996—was to be reevaluated as an adult. Figure 1 shows the natural experiment we were able to use. Most children who had an 18th birthday after August 22, 1996, were reevaluated, and many removed from SSI as adults. In contrast, nearly all children with an 18th birthday before this date escaped the reevaluation and were allowed onto the adult program.

Figure 1 – SSI removal increases criminal justice involvement

This rule thus created an unlucky group of young adults just after the birthdate cutoff who, despite being no different in health or earnings potential than the individuals just before the cutoff, were much more likely to be removed from SSI at 18. Since the only difference between the young adults on either side of the cutoff is the likelihood of receiving a review and being removed, we were able to compare the adult outcomes between the two sides to measure the effect of being removed from SSI. We focus on two main outcomes: formal employment and criminal justice involvement. To measure criminal charges and incarceration, we created the first-ever link of data from the Social Security Administration to criminal records using data from the Criminal Justice Administrative Records System.

Photo by Allef Vinicius on Unsplash

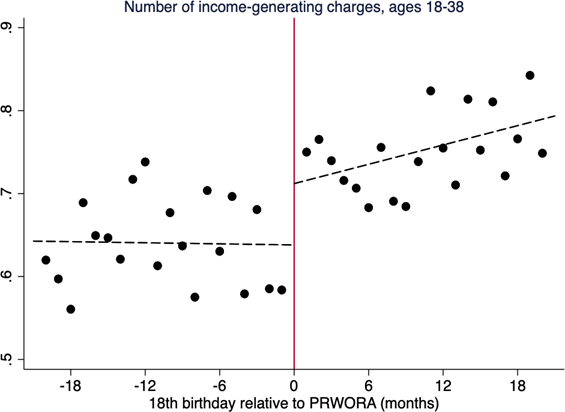

We find that SSI removal at 18 increases the number of criminal charges by 30 percent. Figure 2 shows the sharp increase in the number of criminal charges at the cutoff, meaning that those young adults who received a review and were removed from SSI had more criminal charges as a result. Importantly, the increase in charges is concentrated almost entirely in illicit activities that are intended to generate income—theft, burglary, robbery, fraud, drug distribution, and prostitution. For men, the effects are concentrated in theft, burglary, and drug distribution, while for women they are concentrated in theft, fraud (e.g., identity theft), and prostitution. In contrast, there is very little increase in violent crime or other non-income-generating crimes.

Figure 2 – Increasing criminal charges following 1996 welfare reform

Notes: Top figure plots the likelihood of receiving an age 18 medical review and the likelihood of receiving unfavorable age 18 review (i.e., removed from SSI at age 18). Bottom figure plots total number of income- generating charges between ages 18–38 years. Sample is SSI children with an 18th birthday within 18 months of the August 22, 1996, cutoff who reside in a county with CJARS coverage. See Deshpande and Mueller-Smith (2022) for details.

Our finding suggests that many of these young adults attempt to replace the SSI income they have lost with income from illicit activity. In fact, over the two decades following SSI removal, the effect of SSI removal on the likelihood of having a criminal charge associated with income generation is about twice as large as the effect of SSI removal on the likelihood of maintaining steady employment. Moreover, the effects on criminal activity are highly persistent: even as the young adults approach the age of 40, the effect of being removed from SSI at age 18 continues to influence the likelihood of facing a criminal charge. Much of the persistence can be explained by the Great Recession, which appears to have amplified the effects of SSI removal.

The increase in criminal charges resulting from SSI removal has real consequences for both the young adults removed from SSI and for society. For the young adults, the likelihood of incarceration each year increases from five percent to eight percent, because of SSI removal. There is substantial evidence that being incarcerated and having a criminal record have adverse consequences on future outcomes. We calculated that the costs of enforcement and incarceration nearly eliminate the savings to the government from lower spending on SSI benefits. Moreover, the cost to the victims of the increased criminal activity is staggering: $85,600 per SSI removal based on our calculations using conservative assumptions.

Implications for welfare policy

What do the effects of removing young adults from SSI tell us about the effects of cash welfare more generally? To be sure, young adults removed from SSI are a specific population: they had disabilities as children and come from poor families. But other factors suggest that the results may be generalizable to programs like the expanded child tax credit or a universal basic income. Like those proposed programs, SSI provides a sizable cash benefit to low-income households. The population of SSI recipients who are removed from SSI are more like the general population than the average SSI recipient. Moreover, we find effects of SSI removal on criminal justice involvement on every observable subgroup. Our results are consistent with other research suggesting that income affects criminal justice involvement.

More generally, our results question the historical focus of welfare policy on the discouragement of work. We show that while SSI does indeed discourage formal employment among young adults, its much larger effect is to discourage criminal activity. For these young adults, maintaining steady employment in the formal labor market may not be feasible whether they receive SSI benefits. There may be insufficient jobs to absorb them into the labor market, or they may have insufficient skills to compete for employment. Many instead turn to criminal activity to recover the lost income after they are removed from SSI, with staggering consequences for their own lives and for society at large.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Does Welfare Prevent Crime? the Criminal Justice Outcomes of Youth Removed from Ssi’, in The Quarterly Journal of Economics

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3vQq2vp

About the authors

Manasi Deshpande – University of Chicago

Manasi Deshpande – University of Chicago

Manasi Deshpande is an assistant professor of economics at the Kenneth C. Griffin Department of Economics at the University of Chicago, a faculty research fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and a visiting economist at the Social Security Administration. She received her PhD in economics from MIT in 2015. Her research focuses on the optimal design of social insurance and social safety net programs.

Michael Mueller-Smith – University of Michigan

Michael Mueller-Smith – University of Michigan

Michael Mueller-Smith is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Michigan, faculty associate at the UM Population Studies Center, and director and co-founder of the Criminal Justice Administrative Records System. He received his PhD in economics from Columbia University in 2015. His research focuses on crime and the justice system in the United States.