In many elections, emotions are often just as, or even more important than, facts in voters’ minds. But how do candidates’ characteristics affect the way they use emotional appeals in their campaigns? In new research, Zack Scott and Jared McDonald find that women candidates use more appeals to joy than men, Republicans invoke fear more than Democrats, but not disgust, and that White and Black candidates use emotional appeals in the same ways. They write that these findings show that there is an unequal playing field in US politics, where some candidates can lean into emotions that reflect public sentiment, while others must steer clear.

In many elections, emotions are often just as, or even more important than, facts in voters’ minds. But how do candidates’ characteristics affect the way they use emotional appeals in their campaigns? In new research, Zack Scott and Jared McDonald find that women candidates use more appeals to joy than men, Republicans invoke fear more than Democrats, but not disgust, and that White and Black candidates use emotional appeals in the same ways. They write that these findings show that there is an unequal playing field in US politics, where some candidates can lean into emotions that reflect public sentiment, while others must steer clear.

Politics, and especially campaigning for political office, is about emotions as much as it is about issues and facts. Emotions and rationality work hand-in-hand, and thinkers since Aristotle over 2,000 years ago have noted that persuasion is often more about how the audience feels rather than just what they think. More contemporary research shows that a candidate’s ability to build an emotional connection with the electorate affects their ability to win over voters.

But what if candidates can’t all appeal to emotions equally? That might give some candidates a leg up on others if the ability to provide “emotional representation” is not distributed equally among political office seekers. This insight could reveal patterns of the type of candidates that tend to win elections.

Put another way: Senator Elizabeth Warren, a contender for the 2020 Democratic Party presidential nomination, said in a campaign email, “Over and over, we are told that women are not allowed to be angry. It makes us unattractive to powerful men who want us to be quiet… Well, I am angry and I own it.” What she contended is that pervasive, sexist stereotypes limit the ability of women candidates to invoke anger. The result is that an electorate that is angry and wants a candidate who understands their anger will systematically prefer men candidates, who can match their anger, over women candidates, who are constrained from doing so. While she was willing to buck that trend, she accepted that she would pay an electoral penalty for doing so.

Prior research on candidates’ use of emotions in campaigns focuses primarily on the strategic incentives behind getting emotional. In a new research article we go beyond these strategic considerations to evaluate how candidates’ group identities might create constraints and incentives on the use of emotions. We focus on three group identities: gender, partisanship, and race. Using a collection of speeches made by candidates in presidential primaries from 2000 through 2020, plus the EmoLex emotional sentiment dictionaries, we examine whether candidates differ in their use of emotions based on their group identities.

“Elizabeth Warren” (CC BY-SA 2.0) by Gage Skidmore

Women candidates use more joy appeals than men candidates

An expansive literature notes that women politicians face a “double-bind” where they must appear feminine in accordance with assumptions concerning their gender but also appear masculine in accordance with assumptions about their occupation. In contemplating how this double-bind would affect the use of emotions, we noted a political archetype that seemed to straddle the lines between masculine and feminine stereotypes: the happy warrior. Happy warriors are fighting but doing so without perceived hyper-masculine aggression. This seemed to be an archetype that women candidates could adopt, with the emotional calling-card being joy.

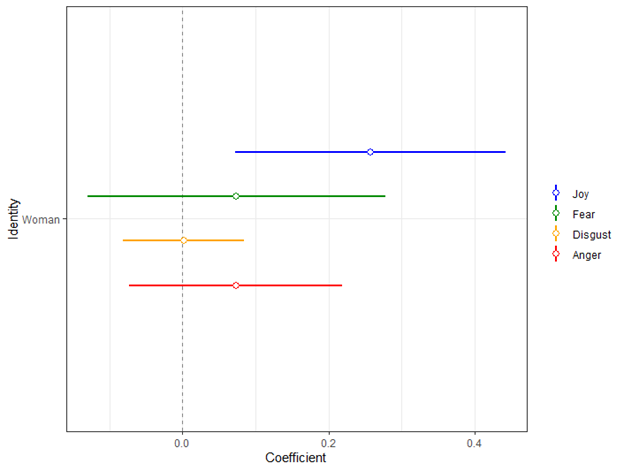

As Figure 1 shows, we do in fact find that women candidates use more joy appeals than men candidates, neatly in line with our expectations. Furthermore, this was the only difference in emotional appeals by candidate gender that we found. Contrary to Senator Warren’s assertion, we don’t find that women candidates use less anger than men candidates. Yet their increased use of joy language may help protect women candidates from the perception that they are excessively angry or aggressive.

Figure 1 – Effect of Candidate Gender on Emotional Appeals in Speeches

Figure plots the coefficient estimates (and 95% confidence intervals) of the candidate’s gender variable in models of the amount of emotional appeals in presidential primary speeches.

Republicans invoke fear more than Democrats (but not disgust)

The changing demographics of the American polity have produced a rise in white identity politics within the American right in conjunction with growing anxiety concerning Whites’ perceptions of the threat posed by other groups. This is combined with a well-established correlation between conservatism, behavioral authoritarianism (typically measured as support for discipline over creativity in child-rearing), and fear. Survey respondents who identify as more conservative also tend to emphasize the importance of discipline when raising children and tend to be more powerfully motivated by fear appeals.

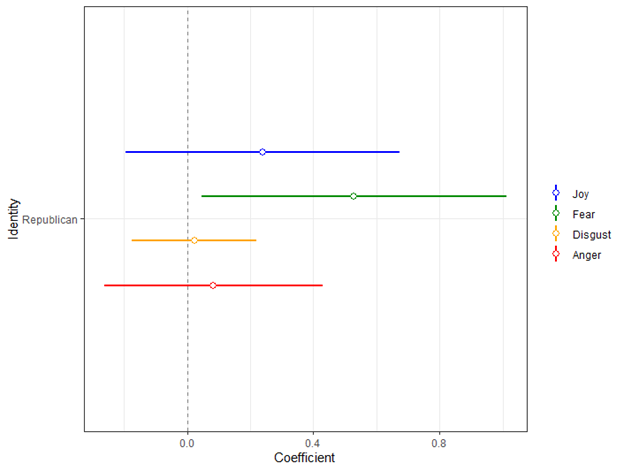

The combination of these two things led us to expect that Republican candidates use more fear appeals than their Democratic counterparts. Again, the results (shown in Figure 2) backed up our expectations.

Figure 2 – Effect of Candidate Partisanship on Emotional Appeals in Speeches

Figure plots the coefficient estimates (and 95% confidence intervals) of the candidate’s party variable in models of the amount of emotional appeals in presidential primary speeches.

We also expected that Republicans would invoke feelings of disgust in their appeals than Democrats. This expectation was tied to the correlation between conservatism, a preference for moral purity, and stronger reactions of disgust to things like diseases. But we found that Democrats and Republicans use disgust to the same degree.

No difference in anger between Black and White candidates

Our final expectation dealt with the use of anger by White and Black candidates. We expected Black candidates to reject using anger, relative to their White counterparts, in order to avoid negative stereotypes about Black anger. This was an expectation in line with prior scholarship as well as conventional wisdom. There was a reason that the idea of the first Black president needing an “anger translator” was humorous: It rested on a shared assumption that a Black politician would be sanctioned for anger.

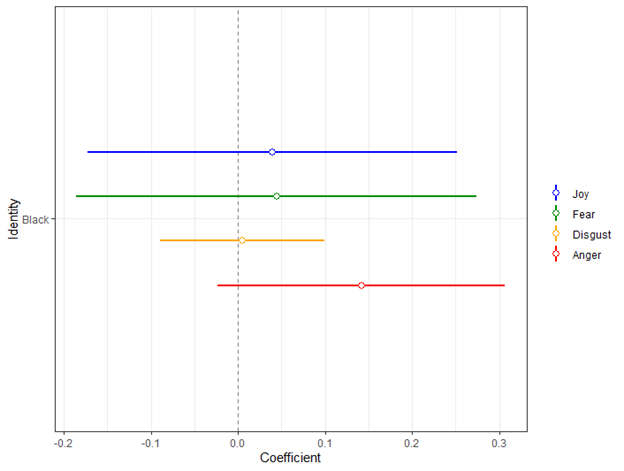

Yet the results (Figure 3) didn’t back up this expectation. At least in presidential primaries, Black and White candidates use anger to a statistically similar degree. In fact, we didn’t find any differences in the use of any emotion by the candidates’ race.

Figure 3 – Effect of Candidate Race on Emotional Appeals in Speeches

Figure plots the coefficient estimates (and 95% confidence intervals) of the candidate’s race variable in models of the amount of emotional appeals in presidential primary speeches.

Emotions, and how politicians use them, matter

Altogether, we find some important differences in the use of emotions based on candidates’ gender and partisanship. Some candidates appear to recognize that the public will respond more favorably to certain types of emotional appeals than others. This means that some candidates, based on their group identities, face a barrier to reflecting the emotions felt by those they seek to represent. This emotional representation, we contend, is often overlooked in the emphasis of the importance of how candidates tend to represent the interests of their own groups and parties. But this is something that’s important to consider if there is anything that can be done to create a level playing field for candidates of all backgrounds.

At the same time, the relationships do not always conform to our expectations. That Black candidates do not avoid anger, suggesting there is an overriding value to using anger in appeals for votes regardless of concerns that negative group stereotypes could create electoral sanctions, is a prime example. We thus see the topic of emotional rhetorical language as highly contextual and ripe for future research.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Tell Us How You Feel: Emotional Appeals for Votes in Presidential Primaries’ in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3zRwqDM

About the authors

Zack Scott – University of Rhode Island

Zack Scott – University of Rhode Island

Zack Scott is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the University of Rhode Island. His research interests include political communication, presidential primary elections, mass media, political parties, elite rhetoric, and populism. His research has been published in American Politics Research, the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion, and Parties; Electoral Studies; and Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly.

Jared McDonald – University of Mary Washington

Jared McDonald – University of Mary Washington

Jared McDonald is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at the University of Mary Washington. His research examines how American voters evaluate politicians and hold them accountable in an environment increasingly characterized by high levels of polarization and strong partisan identities. His work has been published in The Journal of Politics, Public Administration Review, and Political Behavior, among others.