While each election cycle is unique, events, some from the last cycle and some from centuries ago, can impact contemporary elections. Beginning by highlighting how the evolution of the US’s now familiar borders have created the contemporary election map and ending by considering how January 6th may influence the upcoming midterms, Madison Imiola and Peter Finn consider four ways this influence plays out.

While each election cycle is unique, events, some from the last cycle and some from centuries ago, can impact contemporary elections. Beginning by highlighting how the evolution of the US’s now familiar borders have created the contemporary election map and ending by considering how January 6th may influence the upcoming midterms, Madison Imiola and Peter Finn consider four ways this influence plays out.

- Looking ahead to elections across the US in 2022, our mini-series, ‘’The 2022 midterms‘, explores aspects of elections at the presidential, Senate, House of Representative and state levels, and also reflects on what the results will mean for US politics moving forward. If you are interested in contributing, please contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (finn@kingston.ac.uk).

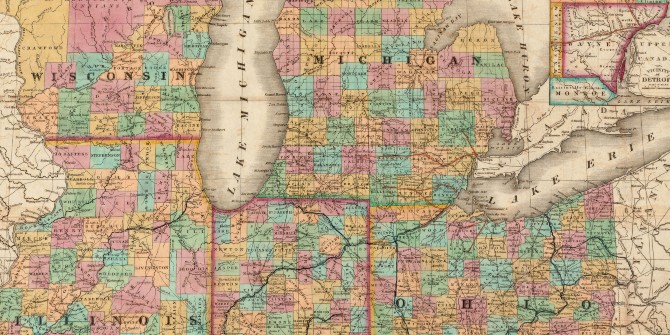

US Borders

We are used to thinking about the US in its current geographic shape, with elections mapped inside these borders. However, the current makeup of 50 states, Washington DC, and overseas territories is relatively recent, with Alaska and Hawaii, for instance, only gaining statehood, and thus federal representation and electoral college votes, in 1959.

Throughout US history there are counterfactuals that could have led to very different electoral maps than those we are familiar with. How would the US look had Napoleon Bonaparte not given up his ambitions for a North American empire, and the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, which saw France sell land only recently acquired from Spain, not occurred, or perhaps the same land been acquired in a more piecemeal fashion? Would all the states now located on the vast tracts of land concerned such as Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma have been divided into the same states, or some other unknowable formulation? Likewise, the land acquired via the US Mexican War of the 1840s? This land (which could have been colonized by the UK in the 1830s), was linked with the young country’s ambitions for westward expansion captured in 1845 by John O’Sullivan in the term Manifest Destiny. If the land acquired from Mexico had not been, would states such as California, Nevada, and Utah now form part of a northern powerhouse within modern day Mexico?

We clearly can never know the answers to these questions, but what asking them does is highlight other possible historical journeys the US could have taken. Considering such journeys also allows us to glimpse how the borders of the US could look different, with the flip side of this being that one can understand how the history of the US has created the electoral map we are now familiar with.

State Boundaries

As with overall US borders, it is possible to imagine different contemporary election maps had US history, and thus the internal US borders, developed differently. One prominent example of this is the secession of West Virginia from Virginia that occurred during the US Civil War of the 1860s. Causes for this secession included, but were certainly not confined to, an objection to slavery by some in the North Western part of the original state of Virginia. The creation of West Virginia in 1863 saw the addition of two US Senators to the state that year. The number of US House of Representatives seats allotted to Virginia fell from eleven in the 1860 apportionment to nine in 1870, with West Virginia allotted three seats in 1870. If Virginia and West Virginia were a single state today, there would be two US Senators instead of the four currently allotted to the two states, 14 house seats (today split 11 for Virginia and 3 for West Virginia), and a single state level electoral system. Given the power the current Senate makeup gives to West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin, such a counterfactual difference could be significant rather than cosmetic.

Similarly, how would the internal dynamics of Wisconsin and Illinois have developed had the border between the two been placed further South on lake Michigan, meaning that Chicago was today within the borders of Wisconsin? Importantly, the current border between the two states arose from lobbying by those in Illinois rather than as an accident of history, showing the role human agency can have in shaping future electoral maps. Would Wisconsin and Illinois have developed differently, and what would be the electoral consequences, if any, for the US Senate delegations, currently three to one in favour of the democrats, of Wisconsin and Illinois, if Chicago was now included in the former rather than the latter state? Moreover, how would such shifts have changed the population tied allocation of US House seats? Finally, would such different state boundaries have led to differences in the state level politics of Wisconsin and Illinois?

As above, the point of asking these questions is not to problematize the current maps, but more to demonstrate that the way in which the US states evolved and were admitted across time has influenced present day electoral maps.

Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library

Redistricting

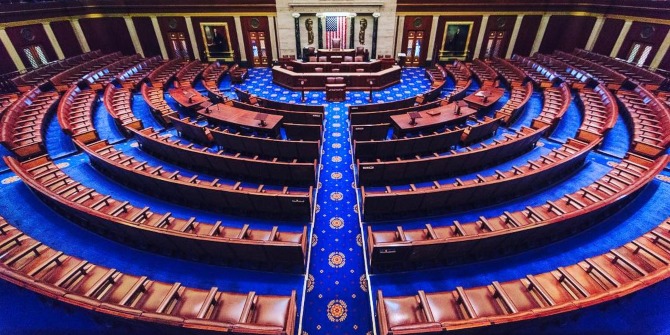

In much the same way that state borders affect electoral maps, so do the boundaries of the political districts within each state. However, the boundaries of these intra-state political districts are much more flexible since all states are required to redraw their voting districts every 10 years after the completion of the federal census.

Each congressional district elects one individual to the US House of Representatives and each state legislative district elects legislators to serve at the state level. In more than 30 states, those same state legislators are then responsible for redrawing district lines after each census. This process affects the outcome of elections as those who are elected can – and do – change the political boundaries of whose votes count where. Redistricting often turns into gerrymandering as states redraw district lines to include or exclude certain populations of voters according to partisanship.

In a recent example of the effects of redistricting, consider that in the 2020 election cycle Donald Trump won the state of North Carolina by a margin of only 1.4 percent and the state re-elected its incumbent Democratic governor. By these measures, North Carolina is a purple state, yet because of gerrymandering Republicans won eight of 13 congressional seats that year. Redistricting is likely to continue affecting elections over the next decade given the challenges of conducting the 2020 census during the COVID-19 pandemic and the US Supreme Court’s 2019 decision that federal courts cannot consider gerrymandering cases.

January 6th

Prior to January 6, 2021, when supporters of then-President Donald Trump stormed the United States Capitol to stop the certification of the 2020 election results, the American government had peacefully transferred political power for more than 200 years (though the US Civil War clearly problematises this statement). The events of January 6th broke the norms of the American political process, but it remains to be seen whether this was a one-time event or if the precedent of peacefully accepting the results of American elections has fundamentally changed.

The upcoming 2022 midterm elections will be the first major test of January 6th’s impact on American elections. Donald Trump, a key instigator for the events of that day, remains the face of the Republican Party for many, and continues to spread the same misinformation about the 2020 election that motivated his supporters to take unprecedented action to contest the election results. If Republicans, especially those with Trump’s endorsement, lose close elections in the 2022 midterms, legal challenges and campaigns of misinformation are likely, while further violence and the outright rejection of election results cannot be ruled out.

Beyond the above, there are innumerable other ways the US election system could be altered had events transpired differently. How might, for instance, tight elections be impacted if Puerto Rico (which has a population larger than more than a dozen US states) had statehood? Could we currently be living through the first half of Obama’s fourth term if a two-term constitutional limit had not been placed on the presidency?

In short, though each election cycle is unique, and fought on the issues driving public opinion and voter sentiment (though given low turnout at midterms, this is not always the same thing), there are also important echoes of the past in each cycle, and the elections that occur within it. A truism that remains whether one considers federal, state, or local level contests.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3fbHaGk

About the authors

Madison Imiola – Washington State Human Rights Commission

Madison Imiola – Washington State Human Rights Commission

Madison Imiola is an MA Human Rights Graduate (2020) from Kingston University. She now works as a Civil Rights Investigator with the Washington State Human Rights Commission.

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Dr Peter Finn is a multi-award-winning Senior Lecturer in Politics at Kingston University. His research is focused on conceptualising the ways that the US and the UK attempt to embed impunity for violations of international law into their national security operations. He is also interested in US politics more generally, with a particular focus on presidential power and elections. He has, among other places, been featured in The Guardian, The Conversation, Open Democracy and Critical Military Studies.