When a candidate changes their view on a policy issue, or “flip-flops,” conventional wisdom is that the public see this as being inconsistent or even untrustworthy. This, however, is not always the case. Andrew Gooch uses an online survey to gauge how Americans would view a candidate who changes their position on immigration policy from when campaigning to holding office. He finds that while changing their mind on an issue does lead to a fall in public support, this effect can be lessened if the candidate is also criticized by the media or other unelected group.

When a candidate changes their view on a policy issue, or “flip-flops,” conventional wisdom is that the public see this as being inconsistent or even untrustworthy. This, however, is not always the case. Andrew Gooch uses an online survey to gauge how Americans would view a candidate who changes their position on immigration policy from when campaigning to holding office. He finds that while changing their mind on an issue does lead to a fall in public support, this effect can be lessened if the candidate is also criticized by the media or other unelected group.

An enduring part of American politics is that politicians often switch positions from one side of an issue to another throughout their careers, often dubbed negatively as “flip-flopping”. Many well-known examples include George H.W. Bush saying “read my lips no new taxes”, or John Kerry’s “vote for the $87 billion [military funding bill] before” voting against it. Even before the term flip-flopping became in vogue, critics regularly used the term “waffling” after Gerald Ford described Jimmy Carter as someone who “waffles and wiggles” on policy. However, flip-flopping occurs frequently among presidents and legislators over the course of their careers, and as a result, it is not obvious that politicians are actually penalized for it.

Historical examples of flip-flopping have their own rich circumstances, which are not exactly replicated here, but the pervasiveness of criticisms for flip-flopping in contemporary politics suggests that it comes with reputational cost. This further implies that consistency is a desirable character trait. Using an online survey experiment, I found that candidates can improve their favorability by remaining consistent on immigration policy and are penalized for flip-flopping once taking office. However, criticisms of flip-flopping by unelected groups like voters, the media, and political activists did not further reduce favorability; instead, these criticisms backfired and improved perceptions of the flip-flopping politician.

Politicians are penalized for flip-flopping, but other political factors are also at play to lessen those penalties

When politicians use persuasive justifications, they are also able to ease the negative effects of flip-flopping. The timing of the flip-flopping also matters. Recent flip-flopping is viewed as worse than changing from a position that was held many years ago. This suggests that voters are more forgiving of politicians who might have “evolved” on an issue over a longer period. The public is also more forgiving of flip-flopping when the issue is new and uncertain like an international crisis. Importantly, the public is also sensitive to their own policy views – the public does not punish politicians for flipping toward their preferred policy. Relatedly, politicians will often flip toward a position that has the support of activist groups who donate to campaigns.

Consistency is Valued when Raising the Cap on Asylum Seekers Entering the US

I used an online survey experiment with a convenience sample of nearly 2,700 Americans to evaluate a politician who flip-flops on immigration policy after being elected, specifically raising the cap of asylum seekers entering the United States. The survey experiment presented randomized scenarios that build on each other, allowing for comparisons of a hypothetical politician during a campaign, to taking office, to being criticized for flip-flopping once in office.

Respondents saw one of six possible scenarios to evaluate flip-flopping on asylum seekers: 1) the politician wanted to raise the cap during the campaign, 2) the politician was consistent on raising the cap once in office, 3) the politician switched positions to support not raising the cap once in office, 4) the politician switched positions and was criticized as “flip-flopping” by voters, the media, or political activists. The criticism scenarios were otherwise identical to scenario three. This design allows for measuring the effect of the criticism itself separated from the effect of switching positions.

Photo by Metin Ozer on Unsplash

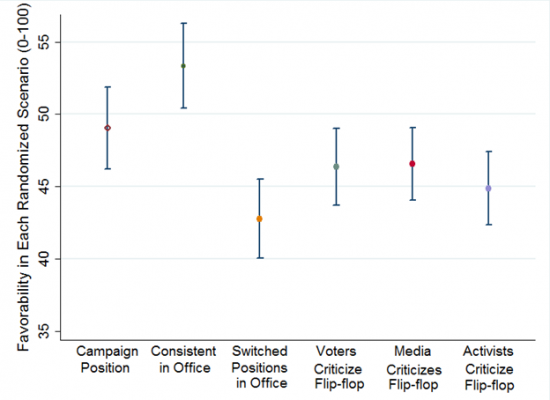

Figure 1 below shows the main results. In the first scenario, the politician simply supported raising the cap for asylum seekers during the campaign, and their average favorability was 49. When the politician was “consistent” – meaning, they still wanted to raise the cap on asylum seekers once in office – the average rating goes up to 53.3, for a difference of 4.3 percentage points. When the politician switches positions on asylum seekers in office, their average favorability drops to 42.8, which is a 10.5 percentage point decrease from the consistency scenario and a 6.2 percentage point decrease from the campaign scenario. This demonstrates that the public does value consistency from politicians on raising the cap for asylum seekers, and that the public downgrades their opinion of politicians when they renege on a campaign promise.

Figure 1 – Consistency on Asylum Seekers is Valued, Flip-flopping is Penalized, but Criticisms from Outside Groups Backfire

Politicians who Flip-flop are Penalized by the Public, But Unelected Groups Criticizing the Flip-flop Backfired

The three bars on the right side of Figure 1 show results for scenarios where the politician is criticized for “flip-flopping”. On average, favorability increased compared to the scenario where only switching positions was presented. A criticism of “flip-flopping” by voters yielded a favorability of 46.4 on average, which represents a 3.6 percentage point increase. Similarly, the difference for the media criticism scenario is an increase of 3.8). Criticism by activists is in the same direction, an increase of 2.1 percentage points, but is not statistically significant at a 95 percent level.

This backfire effect is modest but remains statistically significant in models that control for party identification, self-placed ideology, 2020 turnout, 2020 vote choice, perceived importance of immigration policy, household income, education, and race. I found similar results for a question asking about the politician’s competency as an officeholder. As stated earlier, there are many political factors at play that buffer the negative effects of flip-flopping, and these results show that criticisms from unelected groups might also contribute.

Lastly, switching positions also drastically changed ideological evaluations of the politician. Thus, the average evaluation went from “liberal” when supporting raising the cap to “moderate” when they switched positions.

Media criticism of flip-flops by politicians may backfire

These backfire results speak to the dynamics at play when a politician flip-flops. The intended purpose of criticizing a politician for switching positions is to point out inconsistencies; that it is a character flaw to switch positions from those expressed during the campaign. For example, the New York Times or PBS reporting on Joe Biden’s flip-flop on asylum seekers, or the opinion editorial by Fox News on Biden’s flip-flop on the border are intended to be negative judgements. My results show that the public does value consistency and punishes flip-flopping, but criticisms by unelected groups like the media might not hurt politicians further. These criticisms might be interpreted as excessive, and that they are simply “piling on”.

These results might also demonstrate why politicians will sometimes “play the victim” when being criticized. Instead of defending the substance of the criticisms, some political justifications devolve into personal attacks about those who are doing the criticizing. The most prominent example might be when politicians attack the media as an institution after a negative news story. The backfire effect that my research has found suggests that these strategies might help mitigate the repercussions of flip-flopping.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Candidate Repositioning, Valence, and a Backfire Effect from Criticism’, in American Politics Research.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/3A5QLGt

Great insight!! Who would have thought that?