In The Aesthetic Cold War: Decolonization and Global Literature, Peter J. Kaliney explores how the use of soft power during the Cold War played an intrinsic role in the development of intellectuals working within decolonised regions. This book is an intriguing read for those interested in understanding the Cold War and situating the relationship between the state and anticolonial writers, writes Christina Obolenskaya.

The Aesthetic Cold War: Decolonization and Global Literature. Peter J. Kaliney. Princeton University Press. 2022.

Historically, politicians have both feared and embraced the book. During the Cold War, the US and Soviet Union launched cultural diplomacy programmes aimed at swaying readers to their respective ideological sides through the medium of literature, influencing decolonial thought. In The Aesthetic Cold War: Decolonization and Global Literature, Peter J. Kaliney explores how soft power during the Cold War played an intrinsic role in the development of intellectuals working within decolonised regions.

In the past, the literature of decolonisation has been siloed from the propagandistic pressures exerted by the state during the Cold War. Kaliney insists that developments in decolonial thought and the Cold War need to be discussed in conjunction with conversations around the emergence of a global literary culture. Kaliney analyses how authors including Eileen Chang, Doris Lessing, C.L.R James and Claudia Jones were caught at the intersections of state and aesthetic autonomy as they attempted to pursue their own creative freedom in a politically tense time.

Both the US and Soviet Union granted writers from sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, the Caribbean and Latin America support through financial aid, the publication of literary journals, staging literary conferences and more. Cultural goodwill programmes gave dancers, authors, musicians and artists a platform. Extensive literature exists around how Martha Graham promoted Cold War propaganda through dance, and jazz musicians like Louis Armstrong were used to fight communism.

According to Kaliney, the Cold War wielded opposing pressures on writers from decolonising regions. Both sides created unprecedented opportunities for authors to have their works circulated on a global scale. Authors like Eileen Chang teamed up with the United State Information Agency (USIA), the cultural diplomacy offshoot of the US State Department, and received financial support to pursue publishing endeavours.

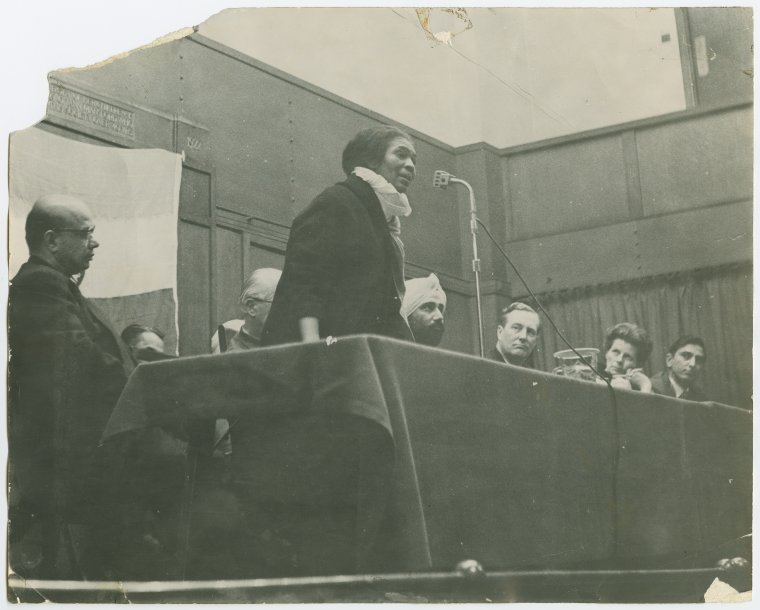

But strings came attached with this outpouring of support in the hope that authors would take a stand for or against communism. Intellectuals were surveilled, censored and imprisoned for writing words. It was not only the practice of Soviet and Chinese forces to censor authors — the FBI in the US and MI5 and MI6 in the UK monitored intellectuals, with particularly keen observation of queer and African diasporic writers. MI5, the British counter-intelligence and security agency, had spies vetting Doris Lessing’s travel documents, tracking her calls and mail correspondence and limiting her right to move around. However, Lessing experienced a lesser degree of monitoring from the British security forces in comparison to the treatment of Black dissidents in the US who were more heavily scrutinised. The FBI collected over 1000 pages of notes on Claudia Jones, a Trinidadian journalist and activist, who was incarcerated on Ellis Island and later deported out of the country.

Image Credit: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. ‘Claudia Jones delivering a speech while on Japan trip.’ The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1955 – 1964. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/9079debf-e885-31d1-e040-e00a18066980. No Known Copyright Restrictions.

Writers from decolonised regions led active debates around the meaning of indigeneity and the importance of indigenous languages in response to cultural imperialism. There existed a vast difference in how the US handled the matter in comparison to the Soviet Union. The US diplomacy system insisted that English needed to be the main medium of literary exchange, whereas the Soviet Union worked with an expansive model of linguistic plurality. One of the successes of the Soviet cultural endeavour was the translation industry, which ‘may well be the largest more or less coherent projects of translation the world has seen to date’ (91), according to literary scholar Susanna Witt.

The US had countless government branches that were disguised as cultural programmes but were created for the attempted propagandistic control of the masses. In 1962, public denunciation occurred when it was revealed by investigative journalists that the Conference of African Writers of English Expression, held at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, was sponsored by the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), a programme run by the CIA. The conference announced the birth of postcolonial African literature in English and was part of a greater scheme run by the CCF to be active within the region, launching magazines such as Black Orpheus and Transition. The CCF had positioned itself without any pretence about its general political affiliations, instead showcasing the programme’s mission to be the protector of intellectual and aesthetic liberties. Although the CIA concealed its efforts to fund cultural programmes, the US State Department was open about its sponsorship, supporting artists like the writer Langston Hughes.

Backed by the Soviet Union, the Afro-Asian Writers Association (AAWA) was one of the most influential post-war networks designed to develop an anticolonial literary tradition in a global context. An intriguing facet of the AAWA was its lack of reliance on metropolitan circuits of cultural exchange between the expected cities of New York, London and Paris. Instead, the AAWA built a global network with interconnected routes between intellectuals in Almaty, Beirut, Cairo and Colombo. In addition, Soviet cultural agencies helped launch the international quarterly, Lotus: Afro-Asian Writings (1968-1991), which was published in Arabic, English and French. Lotus remains one of the most successful examples of a diverse international literary journal.

From the US side, Black Orpheus and Transition were similar journals, but Kaliney argues that Lotus and Transition should not be pitted against one another as opposites given their state affiliations in the Cold War. The CCF was not strictly capitalist and AAWA was not strictly communist — instead both functioned as international patronage networks. Anticolonial writers would appear in both the CCF and AAWA, signalling that there were no strict boundaries holding authors to choose one side to work with in the Cold War.

The Cold War created an atmosphere that enabled the state to impose its ideals on all aspects of life, including the medium of art. Kaliney’s book is an intriguing read for those interested in understanding the Cold War and situating the relationship between the state and anticolonial writers. Further books exploring the intersections of state policies and literary circles are UNESCO and the Fate of the Literary by Sarah Brouillette, Beyond the Color Line and the Iron Curtain: Reading Encounters between Black and Red, 1922-1963 by Kate A. Baldwin, The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing by Mark McGrul and The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War by Louis Menand. It is vital to acknowledge the interplay between government bodies and artists — at times governments have facilitated artistic work, but they have also been the ones to silence thought.

- This review first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/3WSZxkK