In January 2021 the influence of the online political conspiracy movement, QAnon, came to the fore with the storming of the US Capitol by supporters of Donald Trump. But what has fueled the rise and popularity of QAnon? In new research, Daniël de Zeeuw and Alex Gekker examine how QAnon creates alternate realities for those who engage with it. Through a process of “conspiracy fictioning”, they argue, QAnon content gained credence on mainstream platforms like Facebook and Instagram, eventually with destructive results for the “real” world.

In January 2021 the influence of the online political conspiracy movement, QAnon, came to the fore with the storming of the US Capitol by supporters of Donald Trump. But what has fueled the rise and popularity of QAnon? In new research, Daniël de Zeeuw and Alex Gekker examine how QAnon creates alternate realities for those who engage with it. Through a process of “conspiracy fictioning”, they argue, QAnon content gained credence on mainstream platforms like Facebook and Instagram, eventually with destructive results for the “real” world.

The QAnon political conspiracy movement has gained a lot of traction in recent years. Yet many questions regarding its exact features and development over time remain. How did the posts of a (supposedly) government insider named Q instigate a full-blown conspiracy movement involved in the storming of the US Capitol on January 6th, 2021? And how should we even define QAnon? Is it a conspiracy theory, a new mythology, a social movement, a religious cult, a shadowy instance of psychological warfare, a foreign influence operation, or an “alternate reality game” (ARG)? QAnon is all this and more. Most of all, it is a purposefully ambiguous movement that draws its success from the playful and participatory features of social media platforms.

Tracing QAnon from message boards to Trump rallies

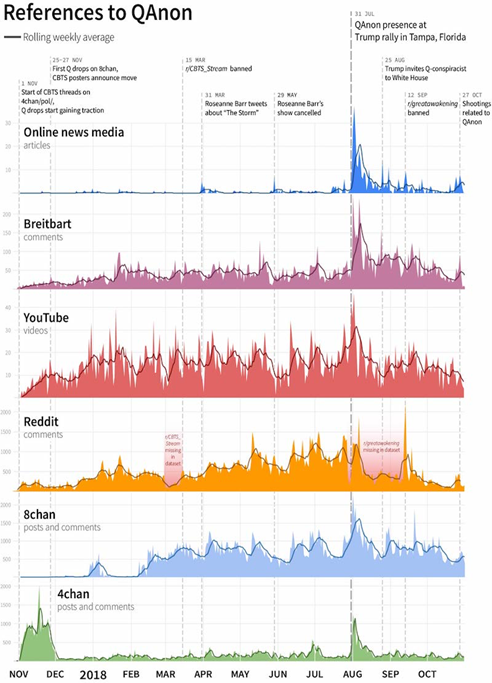

A few years ago, one of us, together with other members of the Open Intelligence Lab at the University of Amsterdam started to investigate the role of social media and news platforms in the initial popularization of the QAnon conspiracy theory between October 2017 and November 2018. Using digital methods, we empirically traced the spread of QAnon from the depths of the website 4chan’s “Politically Incorrect” board to its manifestation at a Trump rally in Florida less than a year later – at which point the mainstream news media first started reporting on QAnon (Figure 1). What we call the “normiefication” of QAnon refers to the process whereby ideas or objects (like memes) travel from fringe online subcultures (like 4chan) to larger publics on other online platforms (like Reddit or YouTube).

Figure 1 – QAnon-related activity across multiple Web spheres between 28 October 2017 and 1 November 2018

Turning to QAnon’s origins in playful online subcultures, in our subsequent research we argue that, to account for the movement’s success, we need to consider how it engages people, by allowing them to playfully construct alternative realities. Supercharged by the ability to participate in the online “world” of social media, QAnon is an instance of online interpretive play that demands deep engagement above all. In other words, it might be immaterial whether one participates in QAnon sincerely or just “trolls” others with it, as social media increasingly blurs the boundaries between play and politics, fact and fiction in culture and society.

QAnon as roleplay

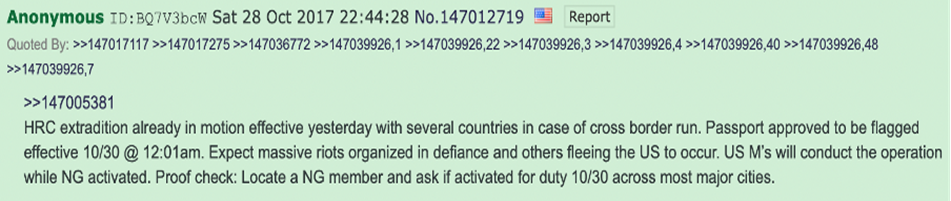

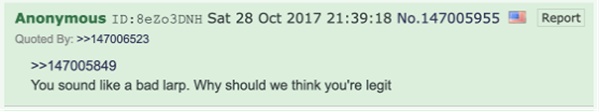

We were especially interested in QAnon’s origins on the anonymous imageboard 4chan, and how it was initially received as a spontaneous act of trolling or LARPing (Live Action Role Playing) that is very common on the platform (but that typically does not lead to the storming of a government building). Indeed, perceptions of QAnon as a LARP were prevalent on 4chan /pol/ from the very start, and even occur in the thread that contains the first ever Q post (Figure 2). To call some- thing a LARP on 4chan typically means to designate it as a trollish in-joke, where all content exists in a suspended state between the “real thing” and its mocking parody.

“Proud Boys at World Wide Rally in Raleig” (CC BY 2.0) by Anthony Crider

Similar to how QAnon was perceived as a potential hoax by 4chan users themselves, several commentators claimed QAnon shares key tenets with the organizing principles of so-called alternate reality games (and might be even connected to the mysterious Cicada 3301 game). ARGs are online collaborative treasure hunts often used as marketing campaigns for transmedia properties and popularized by such early 2000s examples as The Beast for Steven Spielberg’s film AI or I Love Bees for the videogame Halo 2. Traditionally, they share a premise of existing in our own reality, yet with minute changes that immerse the players into the game’s fictional contraptions. ARGs “construct alternative realities that overlay the players’ everyday life and, so-to-speak, charge it with magic”.

Figure 2 – Screenshot of the first Q post on 4chan /pol/, including a comment that suspects Q to be a LARP

Whereas in the early context of 4chan’s Politically Incorrect board the question of QAnon’s authenticity remains highly contested, by the time QAnon reaches Facebook and Instagram its reception and adoption is shaped by very different platform cultures. Already on 8chan and later 8kun, specialized QAnon research boards presuppose the baseline authenticity of Q-drops. On YouTube and Instagram, right-wing influencers see an opportunity to monetize QAnon content, while on Twitter right-wing pundits come to entertain a vested political interest in its reality. As a result, the dynamic surrounding QAnon shifts from suspected trolling or LARP to the semi-religious scripture of a radical political movement. We call this process, whereby belief levels in a conspiratorial narrative change as it travels across platforms, “conspiracy fictioning”.

Belief in conspiracy theories is often seen as part of a new dark age for information literacy where a lack of media literacy – as the ability to critically scrutinize different information sources – accounts for most misguided conspiratorial beliefs. Against this view, danah boyd instead argues that the emphasis on media literacy in education has backfired. In the case of QAnon, the way anons “fiction” an alternative reality through collective interpretation games actually conveys an extreme form of “post-truth media literacy”, in the sense that they possess an intricate understanding of what it takes for any digital content to propagate and “stick”, be it a meme or a conspiracy theory.

Constantly looping back on themselves, such “conspiracy fictions ultimately acquire the power to reshape reality. From Trump’s original allusion to a “coming storm” which set in motion the QAnon fiction, to the actual storming of the Capitol, Q runs its loop: from Storm to storming, from LARP to historical event. Understanding these novel dynamics and the role of the internet in them demands further research, as QAnon might be the first of many disruptions to the way we think about the online world to come.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘A God-Tier LARP? QAnon as Conspiracy Fictioning’, in Social Media + Society.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/423t3Gs