Trade relations between the US and Africa have centred on Congress’s ‘Africa Growth and Opportunities Act’ (AGOA) since 2000, designed to foster the continent’s economic development and prosperity via preferential access to American markets. Yet in the last decade African trade with the United States has stagnated at much the same levels as it was when the Act was passed. David Luke and Jamie Macleod consider how the original impetus behind the AGOA can be revived.

Trade relations between the US and Africa have centred on Congress’s ‘Africa Growth and Opportunities Act’ (AGOA) since 2000, designed to foster the continent’s economic development and prosperity via preferential access to American markets. Yet in the last decade African trade with the United States has stagnated at much the same levels as it was when the Act was passed. David Luke and Jamie Macleod consider how the original impetus behind the AGOA can be revived.

Until the Biden Administration, US-Africa trade policy had been remarkably consistent. The ‘centrepiece’ of this is the Africa Growth and Opportunities Act (AGOA), which has been in place since October 2000, through five separate US administrations. AGOA is a unilateral offering from the US to eligible African counties south of the Sahara that provides preferential – essentially duty-free – access to the US market for qualifying goods.

Since its adoption in 2000, a central objective of AGOA has been to lead to ‘reciprocal and mutually beneficial trade agreements, including the possibility of establishing free trade areas’. The explicit and public aim of the US had been to gradually replace AGOA with ‘comprehensive US-style trade arrangements’ with specific countries. Momentum had gathered in that respect with negotiations launched under the Trump administration for the first such Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the US and Kenya in 2020, which would have served as a blueprint for others.

Since then, a profound shift has occurred in US trade policymaking under the Biden administration. US trade policy has been in a period of introspection, with an ideological clash resolving between a pre-existing paradigm of economic liberalization, which had dominated US trade policy motives for decades, and new trade policy objectives revolving around a ‘unionised worker-centric trade policy’, and climate, environmental and security goals. With this shift has been a deprioritisation of free trade agreements, with Katherine Tai, the US Trade Representative, criticizing them in 2022 as a ‘20th century tool’. In turn, the US suspended in July 2022 the US-Kenya FTA negotiations.

Though no public announcement has yet been issued, and policy could change, US trade policymakers hinted at a US-Africa summit in December 2022 that AGOA will be renewed before it expires in 2025. In taking stock of more than 20 years of AGOA, how well has the initiative performed? How could it be improved? And what is next for US-Africa trade relations?

Two decades of AGOA

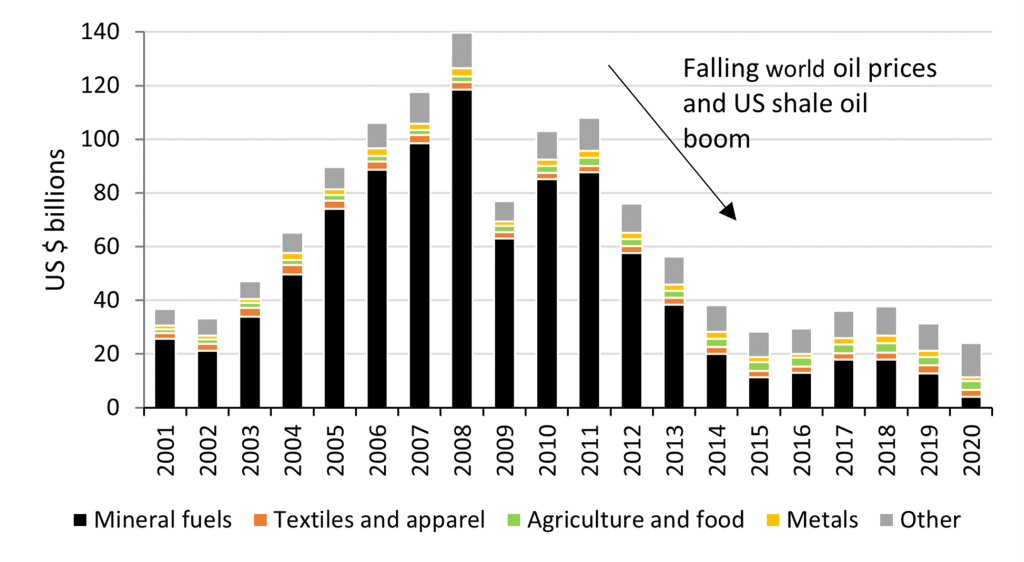

AGOA draws its critics. They can point out that in inflation-adjusted terms, Africa’s exports to the US are no higher now than when AGOA was launched – see Figure 1 below. That would certainly seemingly undermine its stated goal of, ‘encouraging increased trade and investment between the United States and sub-Saharan Africa’.

Figure 1 – US imports from Africa, in constant 2020 US dollars (billion $)

Source: Based on ITC (2022)

A more discerning critic, able to overlook the fact that most of the fall in US-Africa trade is from the displacement of African oil imports with US shale oil since 2011, might still critique the capacity of AGOA to ‘diversify sources of growth in sub-Saharan Africa’. ‘Economic diversification’ is one of the priority areas of the African Union Agenda 2063 and is perceived by many African countries to be critical to their sustainable development. Non-mineral fuel exports from Africa to the US have grown since 2001 but, at around $10 billion annually, are only about equivalent to annual US aid-for-trade disbursements to the continent.

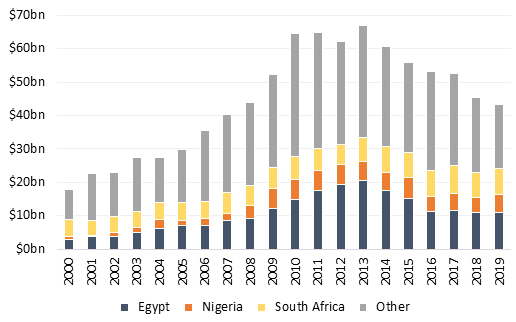

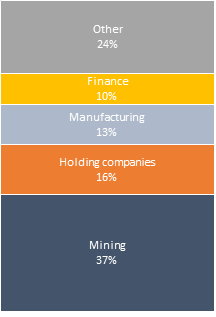

They could point out, too, that US direct investment positions in Africa have also fallen from their relative peak in 2013 – see Figure 2. Those investments have also been overly concentrated in a small number of countries, particularly Nigeria and South Africa, and in the mining sector, which similarly does little to help African countries in their goal to diversify their economies – see Figure 3.

Figure 2 – US direct investment positions in Africa, constant 2020 US$

Figure 3 – US direct investment positions in Africa, by industry, 2020

Why the headline trade and investment figures underappreciate the effects of AGOA

However, in aggregating across a continent and looking only at the headline numbers – which are determined by much more than just by AGOA – it is easy to underappreciate where AGOA has been valuable. Many African countries have recorded specific successes in goods exported under AGOA to the US – including textiles and apparel (from Kenya, Ethiopia, Mauritius, Lesotho, Ghana and Madagascar); automobiles (from South Africa); plant roots and travel goods (Ghana); chocolate and basket-weaving materials (Mauritius); buckwheat, travel goods and musical instruments (Mali); sugar, nuts and tobacco (Mozambique); and wheat legumes and fruit juices (Togo).

“2015_07_31_Mombasa_Port_JPEG_RESIZED_003” (Public Domain) by Ministry of East African Affairs, Commerce & Touri; MEAACT PHOTO / STUART PRICE.

Take Ethiopia, which leveraged AGOA through its national development strategy. A key pillar of Ethiopia’s second Growth and transformation Plan from 2016 to 2020 was nurturing manufacturing-based export industrialization through industrial parks. Textiles and garment exports were the major success, accounting for 95 per cent of exports from Ethiopia’s publicly owned industrial parks. As much as 70 per cent of these exports were destined for the US in 2019, driven by the savings of up to 32 per cent on the value of finished garments exported from Ethiopia because of AGOA according to the World Bank.

We can put this another way. US foreign policy towards Africa has somewhat of a China obsession and US policymaking elites have chastised themselves for losing out to the country in Africa in terms of trade since 2012. Yet what African countries export to the US matters far more than what they export to China. Though China is now the second biggest destination for Africa’s exports after the EU, the continent exports almost three times more manufactures to the US than it does to China, and 35 per cent more agricultural goods. In fact, the US is the third largest destination of African exports of manufactures after the EU and intra-African trade, while 87 per cent of Africa’s exports to China are fuels, ores, and metals. AGOA is part of the reason why and that, in turn, is why African countries such as Kenya, Lesotho and Mauritius have put so much diplomatic capital, and on occasion lobbying funding, into articulating a continuing case for its renewal. AGOA supports the African trade that really matters for the continent’s goal of economic transformation through ‘manufacturing, industrialization and value addition’.

How AGOA can do better and the future of US-Africa trade

Efforts should now focus on ensuring that a renewed AGOA is even more effective than its previous iterations. Here the US seems to be receptive, with US Trade Representative Katherine Tai saying that ‘[AGOA] is no longer enough to boost [African countries’] development and a focus on improving investment is needed’ and that AGOA needs an ‘honest assessment’ to ‘increase utilisation rates’, suggesting openness to its redesign in some form.

There are three ways in which a better AGOA could be achieved. The first is through addressing problems with the programme itself, such as eliminating gaps in the product coverage of the AGOA programme and expanding the country coverage of AGOA to include North African countries. The latter may be possible if African countries can build a convincing case and link to the August 2022 US Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa, which calls for the US to ‘address the artificial bureaucratic division between North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa’.

The second way to improve AGOA is with complementary measures, recognising that, for many of Africa’s poorest countries, market access provisions in themselves are insufficient to motivate change. These complementary supply-side measures include expanding US programmes like Prosper Africa and Power Africa and support to the design and implementation of African countries’ national AGOA utilisation strategies, as well as using trade and investment fairs and the US ‘deal teams’ within US embassies to boost practical trade and investment opportunities, alongside trade and investment facilitation services and trade capacity-building initiatives. New measures could be conceived to invest in and develop green mineral value chains in Africa, in alignment with broader US foreign policy priorities.

The final way in which AGOA could be improved is through linking it explicitly to Africa’s regional integration initiatives and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which was established in 2018, and which is viewed favourably by the Biden administration. That would provide an opening for articulating a continental approach on trade that could link a beyond-AGOA deal to the AfCFTA. Practical first steps would involve introducing supportive elements into AGOA, such as cumulative rules of origin to encourage regional value chains across the continent.

- This post draws on a new book by David Luke et al, How Africa Trades, published in May 2023 by LSE Press.

- Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3WN1WOv