The 2016 election brought concerns about foreign influence on US politics and policy to the fore. And while the US Department of Justice collects data about foreign lobbying, this data is imperfect and there is often no similar data available for other countries. To tackle these information gaps, Mamadou Sacko and Pierre-Louis Vézina propose a new measure of foreign influence using a news-based index, which correlates well with official data. They suggest that their new measure can enhance our understanding of the complex nature of foreign influence.

The 2016 election brought concerns about foreign influence on US politics and policy to the fore. And while the US Department of Justice collects data about foreign lobbying, this data is imperfect and there is often no similar data available for other countries. To tackle these information gaps, Mamadou Sacko and Pierre-Louis Vézina propose a new measure of foreign influence using a news-based index, which correlates well with official data. They suggest that their new measure can enhance our understanding of the complex nature of foreign influence.

Foreign interference has emerged as a pressing concern in recent years, with notable instances such as Russian influence during the 2016 election and Trump’s presidency and the significant presence of Qatari money in think tanks, for example. How can we measure such foreign influence efforts?

What we know about foreign influence

Anyone who attempts to influence policy and public opinion, including tourism and trade promotion on behalf of a foreign country in the US, is required to register with the Department of Justice under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA).

Platforms like Foreign Lobby Watch (part of Open Secrets) have scraped FARA reports since 2016, offering valuable insights into the amount of money spent on foreign lobbying activities from 2016 to 2022. The Department of Justice website also has an API with data on registrations easily downloadable. Researchers have previously scraped information from FARA on 180,000 in-person meetings between foreign agents and individual US legislators spanning 2000 to 2018 and covering 146 countries and 1,200 legislators. They found that when foreign agents have meetings with US legislators, the foreign countries represented benefit from increased financial aid and advantageous product tariffs. They also found that foreign firms whose governments lobby more often benefit from larger subsidies and US government contracts. Others have showed that foreign lobbying captured by FARA was associated with a more liberalized trade policy.

But there’s no similar available data on foreign influence in many countries, and many nations lack such resources. What’s more, many foreign influence efforts go around that law, for example by funding think tanks or via online campaigns, or via local subsidiaries of foreign multinationals. The FARA data is self-reported, so a lot of influencing, and indirect influencing via think tanks is not captured. For example, an FBI investigation into Brookings president John Allen, alleged he secretly lobbied for Qatar, a country which had also contributed over $30 million to Brookings over 14 years. Online campaigns on social media platforms like Facebook can also easily avoid being officially registered as foreign influence. Research which explores corporate clients filing with the Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA) identified the global ultimate owners of all corporate clients, finding that that foreign multinationals account for nearly 20 percent of corporate lobbying spending in 2015–2016. This suggests that the FARA data captures only part of foreign lobbying in the United States.

A new model for measuring foreign influence using the media

The media has been at the forefront in shedding light on many secretive disinformation campaigns. One recent example is a Guardian story on Team Jorge, a secret group claiming responsibility for manipulating over 30 elections worldwide through automated disinformation campaigns on social media platforms. Considering this and other examples, can we use the news media to measure foreign influence and fill the gaps in the official data, and hence enhance our understanding of foreign influence? We believe we can, by using a new approach using news-based metrics and AI technology to analyze the frequency, country associations, and types of foreign influence activities mentioned in the media. Our method involves scraping media sources to analyze the frequency and country associations of mentions related to foreign influence over the years. We aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of foreign influence and fill gaps in official data, enhancing our knowledge of this issue.

Photo by Pinho . on Unsplash

The news data we analysed included news articles downloaded from Factiva and published from 1990 to 2022 containing the words: “foreign influence” and (USA or America or U.S.A or “US of A” or U.S or “United States” or “the US”), from the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, USA Today, CNN, as well as from US Congress documents and reports. We used OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 Turbo API to scrutinize the news articles. Each article was individually sent to the language model using the API which allowed us to verify the relevance of each article to foreign influence in the US, determine the countries involved, and categorize the types of foreign influence activities they were engaged in. Our approach provides a comprehensive, yet detailed exploration of foreign influence that traditional methods might overlook. This method ensures a robust measure of foreign influence, filling gaps in the official data and enhancing our understanding of this complex phenomenon.

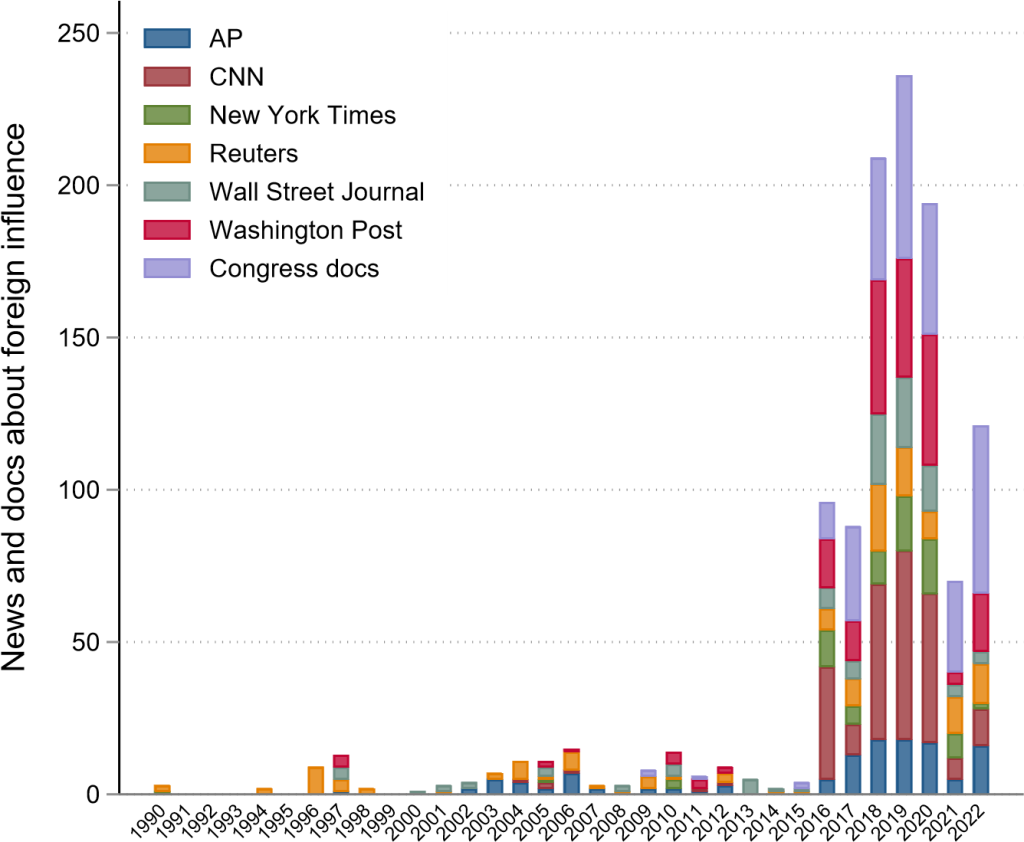

Figure 1 shows the numbers of news articles and Congress documents about foreign influence over the years. There is a major jump in 2016, when Trump was elected, and this issue became more important.

Figure 1 – Foreign influence by year: News mentions

Source: Factiva.

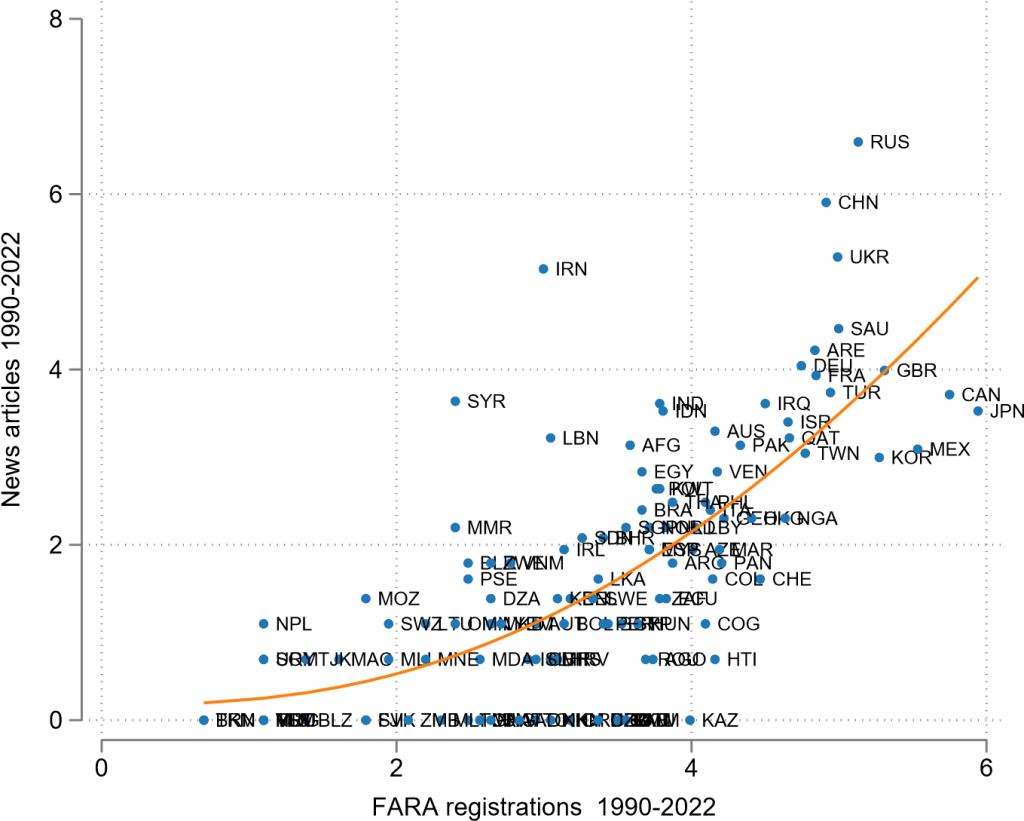

We compare our index with FARA data in Figure 2 and find them to be correlated across countries, indicating that our news-based index does most likely capture foreign influence efforts. Interestingly, our news-based index suggests that countries such as Russia, China, and Iran, as well as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, might be doing even more foreign influencing than the official data suggests. This would be in line with Russia’s involvement in online campaigns for example, or Qatar’s funding of think tank with generous oil and gas windfalls. A noticeable pattern in the data is indeed the role of resource rents and autocracy in causing foreign influence in the US. Qatar, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Russia are all big foreign influencers. But that’s not the only thing going on here. Big countries like Japan and China spend a lot, and a lot of foreign influence is done by tax havens as well, in line with a role for Autocracy Inc., a term coined by Anne Applebaum, referring to the world’s autocrats sharing a common desire to preserve and enhance their personal power and wealth.

Figure 2 – Foreign influence: FARA vs. News mentions

Sources: Factiva and Dept of Justice.

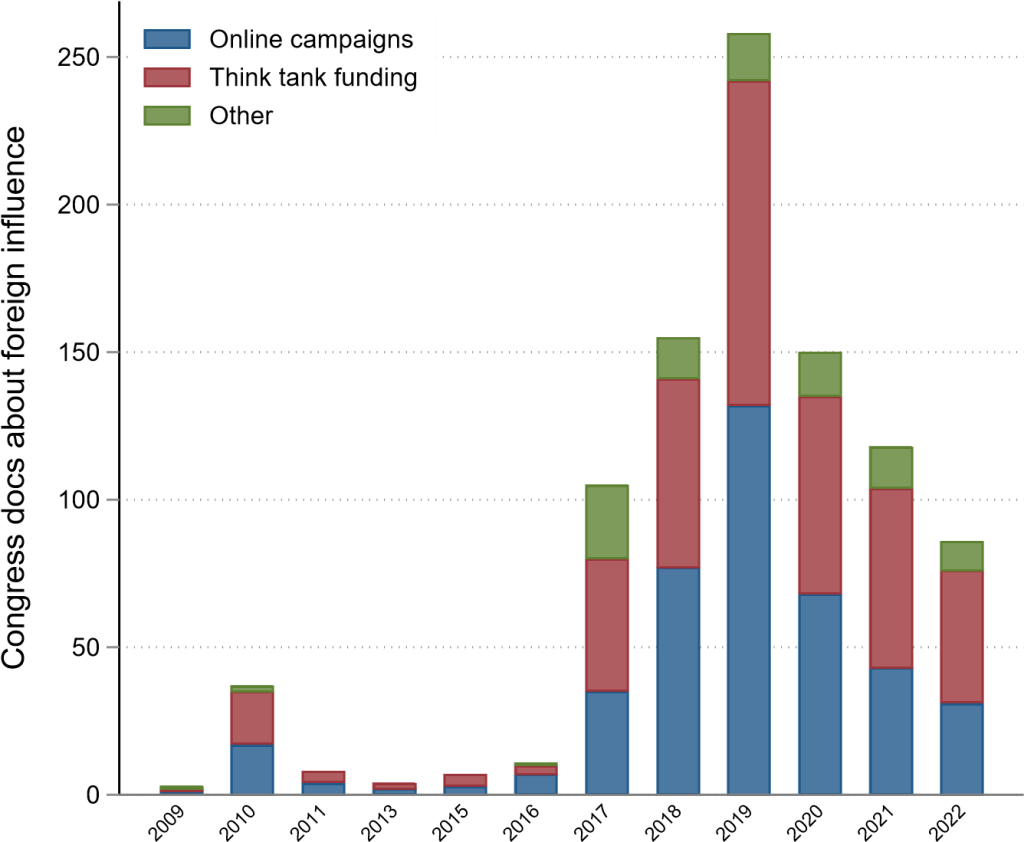

Using OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 Turbo answers to the type of foreign influence the countries mentioned in the news articles were involved in, we found that most were online campaigns during elections, and the illegal funding of think tanks, as shown in Figure 3. This suggests that this data is a good complement to the official FARA data which does not capture such type of foreign influence.

Figure 3 – Foreign influence by year: Docs by type of influence

Source: Factiva

Understanding and quantifying foreign influence is critical for safeguarding democratic processes and ensuring transparent policymaking. While FARA provides valuable data on foreign influence in the United States, many countries lack such data and resources. Exploring additional measures, such as media-based indices, can enhance our understanding of this complex phenomenon. Future research should strive to uncover indirect influencing methods and expand the scope beyond traditional sources to capture the evolving landscape of foreign interference.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3p2Da0n