In many US school districts, there are often significant differences in student suspension rates between African American and Hispanic or Latinx students and White students. Using data on in-school suspensions from more than 6,500 school districts in over 100 US metropolitan areas Jin Lee finds that demographically even school districts report larger differences in in-school suspension rates. She writes that exposure to diversity with only limited interaction between groups does little to diminish existing ethnic and racial prejudice and stereotypes from White majority communities which are more likely to exploit social control and punitive punishment toward African American and Hispanic or Latinx students. More segregated school districts where there is greater interaction, by contrast, are more likely to report smaller differences in in-school suspension rates.

In many US school districts, there are often significant differences in student suspension rates between African American and Hispanic or Latinx students and White students. Using data on in-school suspensions from more than 6,500 school districts in over 100 US metropolitan areas Jin Lee finds that demographically even school districts report larger differences in in-school suspension rates. She writes that exposure to diversity with only limited interaction between groups does little to diminish existing ethnic and racial prejudice and stereotypes from White majority communities which are more likely to exploit social control and punitive punishment toward African American and Hispanic or Latinx students. More segregated school districts where there is greater interaction, by contrast, are more likely to report smaller differences in in-school suspension rates.

Removing children who do not conform to expected behavioral standards from a classroom has become a common strategy for improving academic instruction for the remaining students. In light of recent gun deaths, American schools have increasingly criminalized nonviolent actions and minor misconduct by students. However, disciplinary actions have a greater meaning than a simple administrative procedure. Exclusionary policies such as in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension, and expulsion have been criticized for contributing to a loss of learning resulting from missed time in school and students withdrawing from education. In the US, which has struggled with ongoing segregation and an increasing disparity among racial and ethnic groups, these harmful effects of school discipline have been evident in the experiences of students of a particular race, ethnicity, gender, or income level.

What shapes differing suspension rates?

Although students of color are more frequently suspended and expelled than their White peers in the US, there is a continuing debate about whether race and ethnicity are a predictor of disruptive behaviors. Any prejudice held by a person who refers and suspends children can heighten the racial imbalance in student suspensions. Additionally, students in high-poverty communities may receive more disciplinary actions because their school districts heavily rely on disciplinary policies to easily control children’s misconduct. This suggests that gaps in suspension rates are affected by external factors beyond personal characteristics. In other words, a high proportion of minority students in suspension can be shaped by the challenges that are faced in a child’s everyday life.

The current awareness of the disproportionate rates of student suspensions for African American, Hispanic or Latinx students calls into question whether a school community built with understanding and responsiveness toward minority groups might alleviate the gap in suspensions between White and African American, Hispanic or Latinx students. Because the dynamics of race and ethnicity relations in a community may influence perceptions and attitudes toward student misbehaviors, in recent research I explore the possibility that racial gaps in student suspension rates can close or widen in demographically diverse communities. By examining in-school suspensions in more than 6,500 school districts in 102 US metropolitan areas, my research argues that demographically even school districts report larger differences in in-school suspension rates between African American and White students and between Hispanic or Latinx students and White students.

Does more diverse, mean more or less tolerant?

Just as integrated educational environments can narrow achievement gaps among diverse student populations, exposing students to diverse environments in their everyday lives can be instrumental in reducing racial gaps in school discipline. The intergroup contact hypothesis, first proposed by psychologist Gordon Allport in 1954, argues that limited interaction between diverse groups in segregated communities reinforces discrimination and stereotyping. According to this hypothesis, desegregated schools and school districts reduce racial and ethnic disparities in student suspension by eliminating racial stigma and the biased judgment of student behaviors. However, a simple increase in different groups’ exposure to each other – especially in the US, where ethnic and racial prejudice and stereotypes are a deeply rooted issue – can lead to the majority perceiving the minority as political or economic rivals. Considering that White majority communities are more likely to exploit social control and punitive punishment toward certain groups – the racial threat hypothesis – contrary to the intergroup contact hypothesis, offers a very different perspective on demographic diversity.

“2017/365/215 Lockers.” (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) by kenbauer

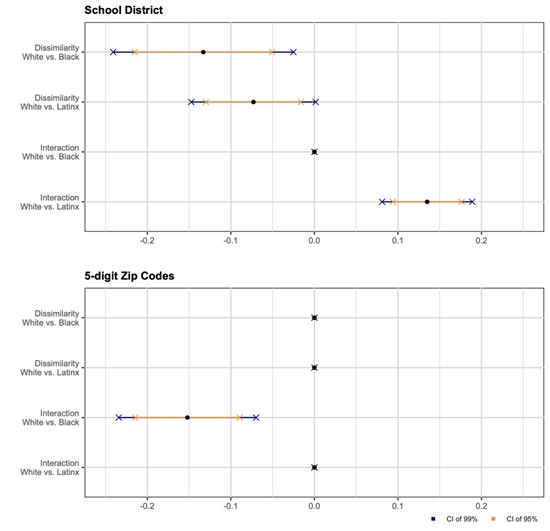

Figure 1 below shows that more-segregated school districts with higher dissimilarity index values (the dissimilarity index measures the proportion of a given racial group that would need to move into other census block groups to ensure complete integration) report smaller differences in in-school suspension rates between African American and White students and between Hispanic or Latinx students and White students. The uneven distribution of African American enrollments across school districts narrows racial gaps in the in-school suspension rates. However, frequent exposure between Black and White populations within zip-code areas moderates the racial disproportion in student disciplinary practices. Additionally, increased exposure to a different race within a zip-code area weakens racial gaps in in-school suspension. This positive effect of integration on the in-school suspension gap between White and Black students is reported only in zip-code areas, not in school districts. The benefit of interracial interaction in a shared space disappears for Hispanic students in school districts.

Figure 1- Confidence intervals for regression coefficients of segregation indices

A call for deliberate inclusiveness

Interest in where suspended and expelled students live is not new, and this interest has grown with the recently increasing implementation of punitive student sanctions, even at the kindergarten level, leading to growing racial gaps in school disciplinary practices. My study challenges the general belief that demographically integrated school districts and communities see smaller racial and ethnic gaps in school discipline. Contrary to the expectation that demographically diverse school districts witness smaller gaps in in-school suspension rates by race and ethnicity due to a better understanding of intergroup relations, students of color in these districts are more likely to be exposed to hostile and unsupportive environments for a frequent use of punitive controls. My research emphasizes structural issues rather than individual characteristics by replicating traditional racial classifications in the field of criminology and criminal justice.

Although my study partly supports the potential of racial threat in exclusionary school discipline practices targeted toward minority students, it also highlights that improved integration brought about by frequent interaction between different races within school districts and neighborhoods may alleviate racial and ethnic gaps in in-school suspension rates. Current approaches to measuring segregation and integration in a plain ratio between subgroups do not sufficiently account for an inverse and unintended effect of diversity on interracial tensions in public space. In diverse school settings, misperceptions about different races and ethnicities can lead to a biased administration of disciplinary school policies, including a growing prevalence of surveillance systems and an expansion of zero-tolerance policies. This calls for the development of not just diverse but also deliberately inclusive school and neighborhood environments.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Potential Racial Threat on Student In School Suspensions in Segregated U.S. Neighborhoods’, in Education and Urban Society

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3q3FJ2A