Immigration can be an immensely polarizing topic. In the American context, specific identity factors make a prospective immigrant more acceptable than others. In new research, Amanda Sahar d’Urso and Tabitha Bonilla explore the importance of identity when it comes to the perception of immigrations from the Middle East and/or those who are Muslim. In doing so, the authors consider whether one’s racial or religious identity is more salient when it comes to the perception of Muslims and Middle Easterners in White American consciousness.

Immigration can be an immensely polarizing topic. In the American context, specific identity factors make a prospective immigrant more acceptable than others. In new research, Amanda Sahar d’Urso and Tabitha Bonilla explore the importance of identity when it comes to the perception of immigrations from the Middle East and/or those who are Muslim. In doing so, the authors consider whether one’s racial or religious identity is more salient when it comes to the perception of Muslims and Middle Easterners in White American consciousness.

Muslim identity and White American perception

Immigration is a hot-button issue in many countries – the United States is no exception. Most Americans prefer some level of immigration but have a strong preference for which types of immigrants should be allowed to come. Immigrants who are Muslim and immigrants who are Middle Eastern are among those who most Americans do not prefer immigrating to the US. But Americans often conflate Muslims—subjects of Islam—with Middle Easterners—members of a racial or ethnic group. The question remains whether Americans hold negative immigration attitudes toward all Muslims, (regardless of if they are Middle Eastern), or whether Americans are specifically wary of Muslim immigrants who are from the Middle East.

We find White Americans do not prefer Muslims of any race to immigrate to the United States. That is, White Muslims are no more or less preferred relative to Middle Eastern, Black, or South Asian Muslims. However, we also find that White Americans believe White Muslims will have an easier time assimilating into American culture relative only to Middle Eastern Muslims. This suggests in the White American public, Muslim identity is one of the most salient factors in determining who should be allowed to immigrate.

Typically, Americans prefer immigrants who are more educated, hold white-collar jobs, and are proficient in English. These characteristics are understood as being key to how well immigrants will assimilate into the American economy as well as American culture. While socioeconomic factors—such as occupation and education—are readily associated with assimilation, sociocultural factors like religion are also associated with belonging. Most notably, White American identity is closely associated with being Christian and many Americans do not prefer immigrants who are Muslim. In fact, when comparing feelings of xenophobia (i.e., fear, hatred, or prejudice against those from another country) versus Islamophobia (i.e., fear, hatred, or prejudice against Islam and Muslims), people tend to hold stronger anti-Muslim sentiments than anti-immigrant sentiments. However, anti-Muslim prejudice may stem from the beliefs that Muslims are cultural outsiders, whereas immigrants more generally may be perceived to have the skills necessary to assimilate.

Identity: the intersections of race and religion

While identity is generally a factor in attitudes toward immigration, there is room to clarify how identity matters. Specifically, Muslim identity is a religious identity, and not a racial identity. Because Muslim migrants could be of several different racial backgrounds, religion should not, theoretically, offer any racial information. However, due to the racialization of Islam—when religious subjects are associated with immutable, biological traits—Muslim identity is often thought of as akin to a racial category. In the US, “Muslim” is often used to refer to anyone from the Middle East, regardless of their religion, and vice versa with “Middle Eastern” often used to mean someone who is Muslim.

One drawback of current research is that it does not consider both religion and race together. That is, although White Americans may be wary of Muslim immigrants, do they still evaluate those Muslim immigrants differently based on their racial background? Perhaps negative sentiment toward Muslims is directed toward the prototype of a Middle Eastern Muslim, rather than any Muslim. Race and religion, together, may play a role in determining who White Americans believe should be in the US.

We conducted an experiment to test the extent to which Americans specifically single out Middle Eastern Muslims or Muslims of any race when thinking about the types of immigrants they prefer in the U.S. White respondents were given two immigrant profiles with several descriptive attributes: education, gender, English proficiency, religion, and country of origin. Each of these attributes could take on several values. For education, the immigrant could have completed elementary school, high school, college, or a master’s degree. The immigrant could have been a male or female, and they may have been intermediate, advanced, or fluent in English. Most importantly for our study, they may have been Muslim, Jewish, or Christian, and either South Asian, Middle Eastern, Black, or White. Each element was randomly picked, constructing unique profiles of hypothetical immigrants.

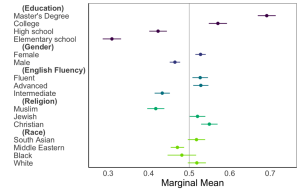

After seeing two immigrant profiles, respondents were asked to pick one profile for whom they would prefer the US to offer a Green Card—which allows someone to become a permanent U.S. resident. They were also asked to rate how well they believe the immigrants were to assimilate into the US. Figure 1 below shows how much the different profile traits mattered. If respondents picked between the two profiles at random, the average would be 0.5—or 50 percent. Values above 0.5 were picked more often than random, and values below 0.5 were avoided more often than random. Consistent with existing data, Figure 1 shows that White Americans prefer immigrants with college or master’s degrees who are women and are fluent or advanced in English. They also prefer Christian immigrants and do not prefer Muslim immigrants or immigrants from the Middle East.

Figure 1. What White Americans perceive to be desirable attributes for immigrants to gain permanent U.S. resident status.

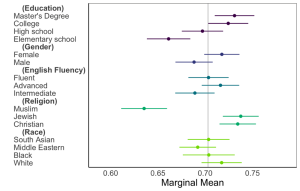

But how likely did these respondents feel these immigrants would assimilate into American culture based on these attributes? In the Figure 2, below, we see that White Americans believe those with master’s degrees are more likely to assimilate and elementary education less likely. They also believe that Christian and Jewish immigrants will be more likely to assimilate but that Muslim immigrants will not. White American respondents did not believe English fluency levels, gender, or race influenced the hypothetical immigrant’s ability to assimilate into American culture. This supports prior research that many may hold anti-Muslim beliefs because of the belief that Muslims are cultural outsiders.

Figure 2. White American perception on the determinants of immigrant assimilation in American society.

The conflation of Islamic identity with ethnic and cultural identity

The evidence thus far indicates that religion supersedes race in how White Americans evaluate immigrants. However, we also consider whether Middle Eastern Muslims—those who fit the archetype of what many Americans believe about both Muslims and Middle Easterners—are particularly scrutinized over and above Muslims from other racial backgrounds.

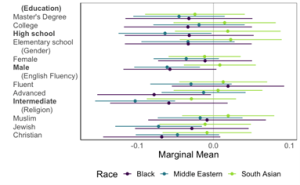

Figure 3 compares Black, Middle Eastern, and South Asian immigrants relative to White immigrants (denoted by the vertical line at 0.0). Any feature that intersects with 0.0 indicates that there is no statistically significant difference in how those features were evaluated for White immigrants and immigrants of another race. When looking at religion, we see that Black, Middle Eastern, and South Asian Muslims are no more or less likely to be given a green card relative to White Muslims. This suggests that there is no additional penalty for Middle Easter Muslims and no benefit for White Muslims among the American public.

Figure 3. What White Americans perceive to be desirable attributes for immigrants to gain permanent U.S. resident status broken up by immigrant’s race.

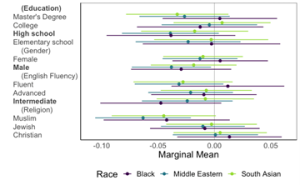

We do see some differences when looking at perceptions of assimilation, however. Black and South Asian Muslims are perceived as being equally likely to assimilate into American culture relative to White Muslims. However, relative to White Muslims, Middle Eastern Muslims are perceived as being less likely to assimilate into American culture.

Figure 4. White American perception on the determinants of immigrant assimilation in American society broken up by immigrant’s race.

Americans often conflate Middle Easterners—a racial or ethnic category—with Muslims—religious subjects of Islam. As a result, research has not focused on parsing the differences between anti-Middle Eastern, anti-Muslim, or anti-Middle Eastern Muslim sentiments. Using our experimental design, we find that race plays only a small role in moderating how White Americans evaluate Muslim immigrants.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Religion or Race? Using Intersectionality to Examine the Role of Muslim Identity and Evaluations on Belonging in the United States‘ in the Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Featured image credit: Photo by Kerwin Elias on Unsplash

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/44skQfK