Monetary sanctions – a set of fees and fines levied on individuals who are in or have left prison – have seen an increase in use. In new research, Michele Cadigan, Alexes Harris, and Tyler Smith explore the growing prevalence of monetary sanctions and examine their impacts on communities. The authors underline the ways the current system of monetary sanctions may create incentives for local governments to be punitive in their imposition of Legal Financial Obligations (LFOs). The effects of these obligations are far-ranging, but ultimately amount to a greater inability for individuals to move forward post-imprisonment.

Monetary sanctions – a set of fees and fines levied on individuals who are in or have left prison – have seen an increase in use. In new research, Michele Cadigan, Alexes Harris, and Tyler Smith explore the growing prevalence of monetary sanctions and examine their impacts on communities. The authors underline the ways the current system of monetary sanctions may create incentives for local governments to be punitive in their imposition of Legal Financial Obligations (LFOs). The effects of these obligations are far-ranging, but ultimately amount to a greater inability for individuals to move forward post-imprisonment.

Legal Financial Obligations and the costs of incarceration

Monetary sanctions, also termed Legal Financial Obligations (LFOs), are the fines, fees, surcharges, interest, and restitution imposed by courts on people who interact with the criminal-legal system. The use of monetary sanctions, and amounts sentenced, have escalated dramatically over the decades with these financial penalties being the most common form of punishment across the United States. While data do not exist to measure within states, it is estimated that outstanding legal debt in the US totals in the billions. This rise in monetary sanctions is due primarily to the massive criminal-legal expansion of recent decades and the ballooning costs of criminal supervision. As criminal legal expenditures continue to rise, local governments are turning to monetary sanctions to relieve some of these fiscal pressures. In addition to mass incarceration, we are also experiencing an era of mass criminal legal debt.

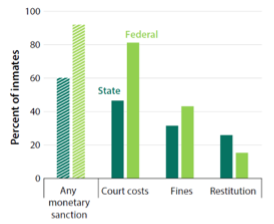

As policymakers grapple with the legacy of mass incarceration, important questions remain about the role and impact of legal-financial penalties. First, individuals returning from prison are saddled with legal debt (see Figure 1). In most jurisdictions, individuals are charged a fee for time spent behind bars and these fees must be paid after their release in addition to any other fines and restitution owed. Second, forms of supervision, such as probation and home monitoring, are predominantly paid for through mandatory court fees charged to individuals placed on these “alternatives” to incarceration. This means that the ability of a person to pay their financial obligations becomes a primary factor in determining if they successfully complete their criminal-legal obligations.

Figure 1. Percent of Prison Inmates with a Court-Imposed Monetary Sanction, by Sanction Type and Governmental Level

Note: Taken from Nine Facts about Monetary Sanctions in the Criminal Justice System by the Brookings Institute. Source data comes from the Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities, BJS 2014.

This raises key questions about the impacts that monetary sanctions have on individuals and their communities. In the discussion below, we outline research evidence that shows how LFOs deepen poverty, further entangle people in the criminal legal system, and impact the reentry process for individuals returning from prison. If we are to address mass incarceration through decarceration and alternative sanctioning, then understanding the negative impacts of legal financial obligations is essential for creating just and equitable policy.

Monetary Sanctions have Serious Negative Impacts

In the largest study of monetary sanctions to date, Harris and colleagues studied the systems of monetary sanctions in eight different states (California, Georgia, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri, New York, Texas, and Washington). They found that each state had a unique and complex system of legal financial obligations in their statutes and that monetary penalties were used frequently for all levels of conviction. Not only do these monetary sanctions go toward paying for court services, but they often make up a significant portion of the general revenue for local governments. Such an arrangement can create perverse incentives for police and court officials who may treat the criminal-legal system as a mechanism for general revenue generation, as was made clear by the now infamous Ferguson Report.

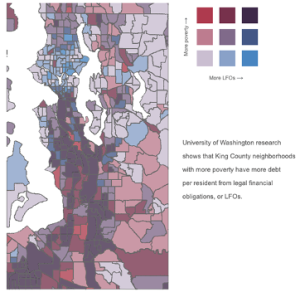

This work also showed that monetary sanctions have serious negative consequences for both individuals and communities. Black, Latino, and Indigenous individuals have higher amounts of legal debt and spend a significant amount of time attempting to resolve their cases compared to white individuals. Furthermore, monetary sanctions impact the ability of people to obtain stable housing and employment which, in turn, impacts their ability to pay their legal sanctions. The financial burden of legal debt also greatly increases stress, which can create and exacerbate health issues. Finally, legal debt tends to concentrate in poorer communities of color which may help contribute to deepening levels of poverty in these communities and wealth extraction (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Note: Taken from UW News reporting on O’Neill, Kennedy, and Harris, Debtor’s Block

Criminal-Legal Debt Hinders Reentry

The harms of monetary sanctions severely hamper individuals returning from incarceration. It is estimated that individuals reentering the community from prison carry about $900 in legal debt and that these debts increase due to fees associated with post-release supervision. This debt increases recidivism, as individuals are required to pay a portion of their earnings back to the government. For individuals who are already facing limited and precarious employment after release, this burden greatly increases their chances of failing to meet their criminal-legal obligations and returning to prison.

Photo by Tingey Injury Law Firm on Unsplash

Monetary sanctions themselves may be linked to greater incarceration rates and thus are counterproductive. Counties with a greater reliance on monetary sanctions for their budgets have been linked to higher incarceration rates for women. One explanation is that courts manage legal debt through repeated court appearances and failure to appear at these hearings can lead to incarceration and further financial penalties. Not only do these appearances increase the likelihood of incarceration, but they also make it hard to maintain stable employment, and people’s abilities to drive legally. This means that simply having legal debt increases your chances of legal jeopardy. Individuals who have had their legal debts paid off interact far less with the court system, including fewer warrants or new debts.

A Two-Tiered System of Justice

Many people, solely because of poverty, can never fully serve their criminal legal punishments when fiscal penalties are involved. The system of monetary sanctions thus creates a two-tiered system of justice that locks poor individuals into the criminal-legal system. Furthermore, the increased use of monetary sanctions to pay for incarceration and other court services increases recidivism and decreases the effectiveness of alternatives to incarceration. In sum, monetary sanctions provide a significant barrier to addressing the harms of mass incarceration. Many people, solely because of poverty, can never fully serve their criminal legal punishments when fiscal penalties are involved.

We suggest several initiatives for addressing these problematic policies. States must abandon “offender-funded” models of criminal justice that puts the burden of paying for government services on the shoulders of those least able to pay. Instead, courts and criminal sanctions should be directly funded through state and local budgets. We also encourage jurisdictions to remove mandatory fines and fees and increase the discretion of judges to waive monetary penalties for those who are indigent and unable to pay. We also suggest removing criminal penalties for non-payment, such as incarceration or the suspension of driver’s licenses. Further criminal-legal entanglement does little to help individuals pay their legal debts and only adds to already overburdened court systems. Of course, these suggestions are only some among many policies that would help to alleviate the burden of monetary sanctions.

Monetary sanctions disproportionately burden the poor, deepen poverty, and hinder individuals as they try to re-enter the community from incarceration. Reformers attempting to end mass incarceration must be aware of the financial limitations of justice-involved individuals and their families and how monetary sanctions impact successful completion of supervision requirements. Without a realistic system, where people can satisfy their obligations and move forward with their lives, the criminal legal system will continue to fail at reaching equal justice for all.

- This article is based on the chapter ‘Monetary sanctions in the age of mass incarceration: addressing the harms of mass criminal legal debt’, in the new book, Beyond Bars: A Path Forward from 50 Years of Mass Incarceration in the United States

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/44Qy9XF