Recent events, such as the US capitol insurrection have raised concerns about the erosion of democracy and democratic norms in the United States. In new survey research, Daniel Goldstein takes a close look at Americans’ attitudes to those who would break democratic norms, such as a commitment to fair elections. He finds that many Americans are happy to financially punish those they see as breaking democratic norms, suggesting that citizens may be more likely to hold one another to account and support democratic institutions than is currently thought by many.

Recent events, such as the US capitol insurrection have raised concerns about the erosion of democracy and democratic norms in the United States. In new survey research, Daniel Goldstein takes a close look at Americans’ attitudes to those who would break democratic norms, such as a commitment to fair elections. He finds that many Americans are happy to financially punish those they see as breaking democratic norms, suggesting that citizens may be more likely to hold one another to account and support democratic institutions than is currently thought by many.

The US Capital Insurrection of January 6, 2021, which aimed to overturn the democratic election of President Joe Biden, was one of the latest attempts to undermine democratic elections in seemingly stable democratic nations. Notably, a significant number of citizens participated in support of undemocratic efforts by a political leader. What factors might reduce citizens’ support for the undermining of democracy? One answer may be rooted in social norms.

Norms, democracy, and voting

Speaking to The New York Times’ The Daily podcast, a participant in the January 6 Insurrection stated that “This whole ordeal has cost me more than you can imagine… My neighbors won’t even talk to me anymore. And we had great relationships. But they all talk and found out. And I’ll be walking out to my car, and see them, and I’ll say hi, and they won’t even say hi back. And that hurts.”

In the aftermath of January 6th, participants appeared to be socially punished for their actions (and, as it turned out, many were also criminally prosecuted). Despite the attempts to undermine democracy, it appears that in the United States, or at least in that participant’s neighborhood, behavior supporting the erosion of democracy was stigmatized. That is, there was a social norm against supporting the undermining of democracy.

A vast academic literature on ‘democratic backsliding,’ i.e., the subversion of factors related to democracy ranging from individual rights and liberties to free and fair elections, has decried the erosion of democratic norms. Yet while this phrase is repeated in academic articles and news headlines, it is seldom defined consistently or rigorously.

In new work, I provide and test a formal definition of democratic norms among citizens, and extend this definition in game-theoretic terms and examine its implications for how citizens vote. I also look at how we can determine – via experiment – whether a type of democratic norm is reinforced by punishment among citizens.

“Vigil4Democracy_SF_IMG_4998-1” (CC BY-NC 2.0) by rawEarth

What are democratic norms?

I define democratic norms as a subset of political norms, and I divide political norms into three general categories (see Table 1). First, there are “political values,” which are an individual’s preferences regarding politically important behavior, e.g., how politicians should act. I distinguish such individual values from inherently social phenomenon that define norms. Norms are divided into two parts: descriptive norms, which simply define how a citizen expects others to behave, and injunctive norms, which specify the type of behavior a citizen expects others to find appropriate. The term “others” here may indicate a focus on the behavior of citizens or politicians.

Table 1 – Typology of Political Norms from the perspective of citizens

Given this general framework of political values and norms, I focus on democratic values and norms regarding the actions and beliefs of other citizens. That is, in a democracy, democratic values indicate how a citizen believes other citizens should behave, descriptive democratic norms indicate how they expect citizens to behave, and injunctive democratic norms indicate what they believe other citizens will find appropriate.

Critically, leading scholars of social norms, such as Christina Bicchieiri of the University of Pennsylvania and others, emphasize that norms are often enforced through some sort of punitive mechanism that harms those who violate the norm. Next, I look at how injunctive democratic norms can be enforced among citizens by punishing those who violate them.

Dictator Game among Citizens

In a survey experiment, I first measure perceived descriptive and injunctive democratic norms. To do so, respondents saw two hypothetical candidates for political office. The candidates differed on several policy and demographic dimensions but were both Democrats. One candidate supported an undemocratic policy position that would reduce the number of polling places in areas supporting Republican politicians. This policy was intended to replicate real-world policies that have been implemented to make it more difficult for political opponents to vote. To determine their norms, respondents were financially incentivized to show which politician they expected other respondents to support in an election (the descriptive democratic norm) and how appropriate they expected other respondents to find the undemocratic policy (the injunctive democratic norm). My results indicate high levels of both types of democratic norms. Next, I examined whether citizens are willing to enforce the uncovered democratic injunctive norm by punishing other respondents who violate the norm by finding it appropriate for the politician to undermine democracy.

To determine this, respondents assume the role of an allocator, or “dictator,” to unilaterally divide a potential $15 bonus between themselves and a passive, matched “recipient”. The respondent is initially allocated $10 and the recipient $5, which the allocator can then shift. Respondents are informed that one of their allocations will be implemented if they are randomly selected to receive the bonus. This approach adds real-world validity to the study by measuring punishment through a behavioral choice.

Respondents first divide the bonus with no information about their partner (which serves to measure baseline generosity). They are then randomly assigned to learn that they have been paired with another respondent who either agreed or disagreed that the position highlighted in the norm elicitation phase was inappropriate or appropriate (depending on their actual answer). The respondents then divide the bonus again. Thus, I compare the baseline of no information and examine how learning about a matched partner’s response to the appropriateness of the undemocratic position affects their bonus allocation.

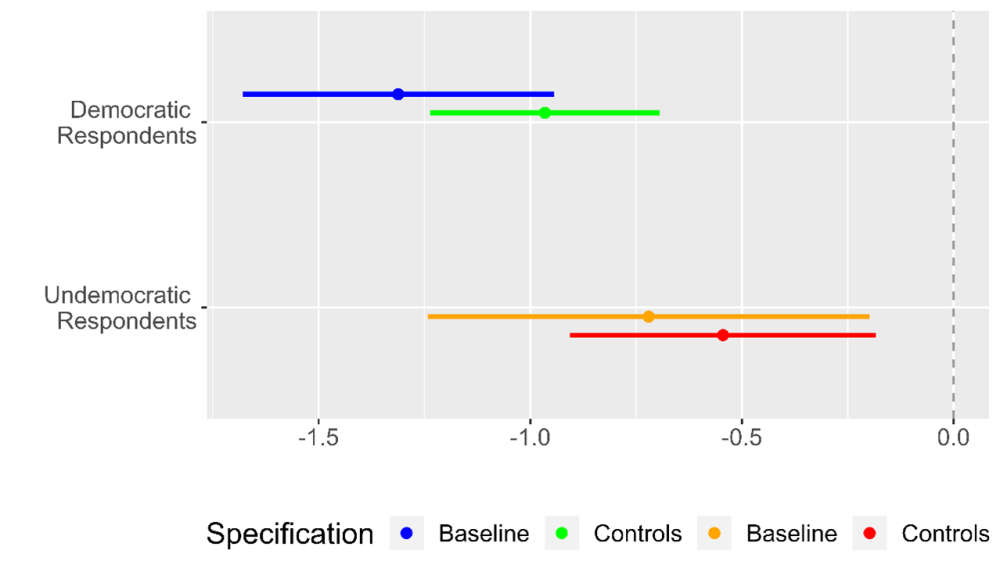

In Figure 1, I separate the results depending on a prior question measuring the respondent’s commitment to democratic values. The points represent the effect of being paired with a respondent who approved of the politician’s undemocratic action and, hence, violated an injunctive democratic norm, conditional on the respondent’s baseline values. The top line in each group is the baseline effect, while the bottom line indicates the inclusion of a set of control variables. At baseline, respondents give their partner about $5 of the potential bonus. For relatively democratic respondents (the top group), norm-violators had their bonus payments reduced by about $0.97-1.31 of the bonus, which is about 23 percent less than what is allocated to a match with someone who was norm adherent. Moreover, even among individuals who indicated a weaker commitment to democracy (the lower group), norm-violators were punished by about $0.54-0.72 of their bonus payment.

Figure 1 – Respondents’ punishment of democratic norm violators by commitment to democratic values

The dictator game provides evidence that US citizens are willing to impose costly punishments on others who support a politician who undermines democracy. By breaking down democratic norms into their descriptive (expected actions) and injunctive (expected perceptions of appropriate behavior) components, I can isolate how an injunctive democratic norm can be enforced among citizens. The result may speak to one critical mechanism by which citizens hold each other accountable in a democracy, which may serve to stabilize and support democratic institutions over the long run.

Will norms protect democracy in 2024?

The upcoming 2024 US presidential election will further illustrate how political norms affect the behavior of citizens. My study suggests that by supporting politicians who seek to undermine democracy, transgressing citizens may be punished by both strong supporters and even those with a relatively weak commitment to democracy. Hence, norms may protect democracy through the threat of altered interpersonal relations. However, in the wake of reports of the erosion of democratic norms, such stigmatization may weaken, leading to greater scope for challenges to democracy, such as through disputed election results. Time will tell how democratic norms may affect the survival of democratic institutions as we approach the 2024 election.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The Social Foundations of Democratic Norms’, in SSRN.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/40FYdE9