Existing analyses have failed to emphasise inflation’s underlying distributional sources and outcomes. Rafael Wildauer, Karsten Kohler, Adam Aboobaker and Alexander Guschanski present a macroeconomic model that analyses how energy price shocks trigger redistribution between workers and firms, and between different sectors of the economy. For them, a windfall tax can redistribute energy profits towards workers, a promising policy tool for reducing inflation without increasing unemployment and income inequality.

Existing analyses have failed to emphasise inflation’s underlying distributional sources and outcomes. Rafael Wildauer, Karsten Kohler, Adam Aboobaker and Alexander Guschanski present a macroeconomic model that analyses how energy price shocks trigger redistribution between workers and firms, and between different sectors of the economy. For them, a windfall tax can redistribute energy profits towards workers, a promising policy tool for reducing inflation without increasing unemployment and income inequality.

Since the summer of 2021, many advanced economies have seen inflation rise above ten per cent. The main policy response has been to raise central bank interest rates. After a brief period of declining inflation, oil prices are currently increasing again, fuelling concerns of a new inflationary surge. Income distribution barely features in the macroeconomic policy discourse on inflation. We argue that this is a significant omission. Periods of high inflation are almost always periods of redistribution of income. In turn, income distribution is a fundamental factor in inflation. Different policy responses also imply different distributional consequences.

We develop a three-sector model of inflation dynamics, building on the theory of ‘conflict inflation’ (Rowthorn, 1977; Blecker and Setterfield, 2019; Hein and Stockhammer 2011) that has recently gained renewed prominence (Lorenzoni and Werning, 2023; Weber and Wasner 2023). Our paper is informed by the literature on increasing corporate profit margins (Weber and Wasner 2023; Unite 2022, 2023; Hayes and Jung 2022). It effectively formalises some arguments within a ‘conflict inflation’ approach that are also made by Weber and Wasner (2023). By proposing a theoretically rigorous framework, we also aim to provide clarity to the ongoing debate about wage-price spirals versus profiteering.

We highlight three insights from our research. First, energy price shocks lead to higher inflation and higher economy-wide profit shares (defined as profits over value added). This implies increased income inequality because of a redistribution of income from labour to capital. Second, a demand shift towards goods and supply bottlenecks increase profit margins (profits over gross output) in the goods sector. Our framework thus also explains increasing profitability outside the energy sector, which has received much attention in the public debate. Third, our policy analysis shows that a windfall profit tax, combined with household transfers, succeeds in curbing inflation while also stabilising real incomes and employment. By contrast, contractionary monetary and fiscal policy and wage restraint have negative effects on employment and income inequality.

A three-sector model

Conflict inflation is based on the idea that inflation arises because workers and firms fight over the distribution of national income. Each party tries to capture a larger share of income by increasing prices and nominal wages respectively. This approach departs substantially from theories that emphasise inflation as ‘always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’

Our analysis considers three shocks that trigger an intensification of this inflationary distributional conflict. First, an increase in energy prices as observed since 2021, which peaked as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Second, a shift in consumption preferences from services towards goods during the pandemic. Third, disrupted supply chains and shortages in crucial inputs constraining the supply side of the goods sector. We go beyond the existing literature by analysing the effect of those shocks on prices in three sectors: domestic energy (capturing countries with a sizeable domestic energy production such as the US and the UK), services and goods. This allows us to analyse income distribution between capital and labour, as well as changes in profitability between sectors.

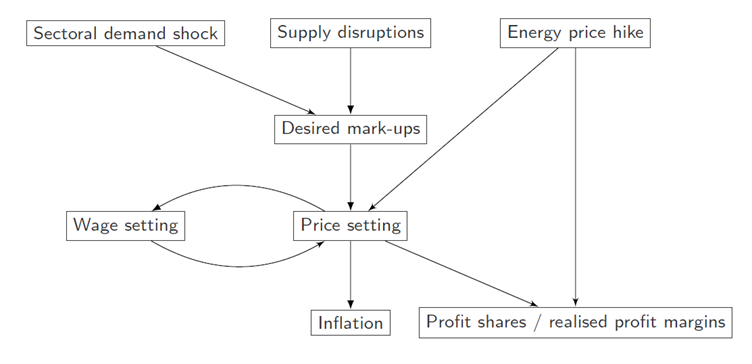

The mechanics of the model are illustrated in Figure 1. The energy shock increases costs for non-energy firms (goods and services), inducing upward pressure on prices to protect profit margins. The sectoral demand shift towards goods, in combination with pandemic-related supply bottlenecks, induces firms to raise markups. This accelerates inflation and leads to divergence in sectoral profit margins. The combined shocks increase inflation, which undermines real wages, and redistributes income towards firms. Workers respond by raising nominal wage demands, in an attempt to protect their real wages. This triggers successive increases in nominal wages and prices.

Figure 1 – Our argument in a nutshell

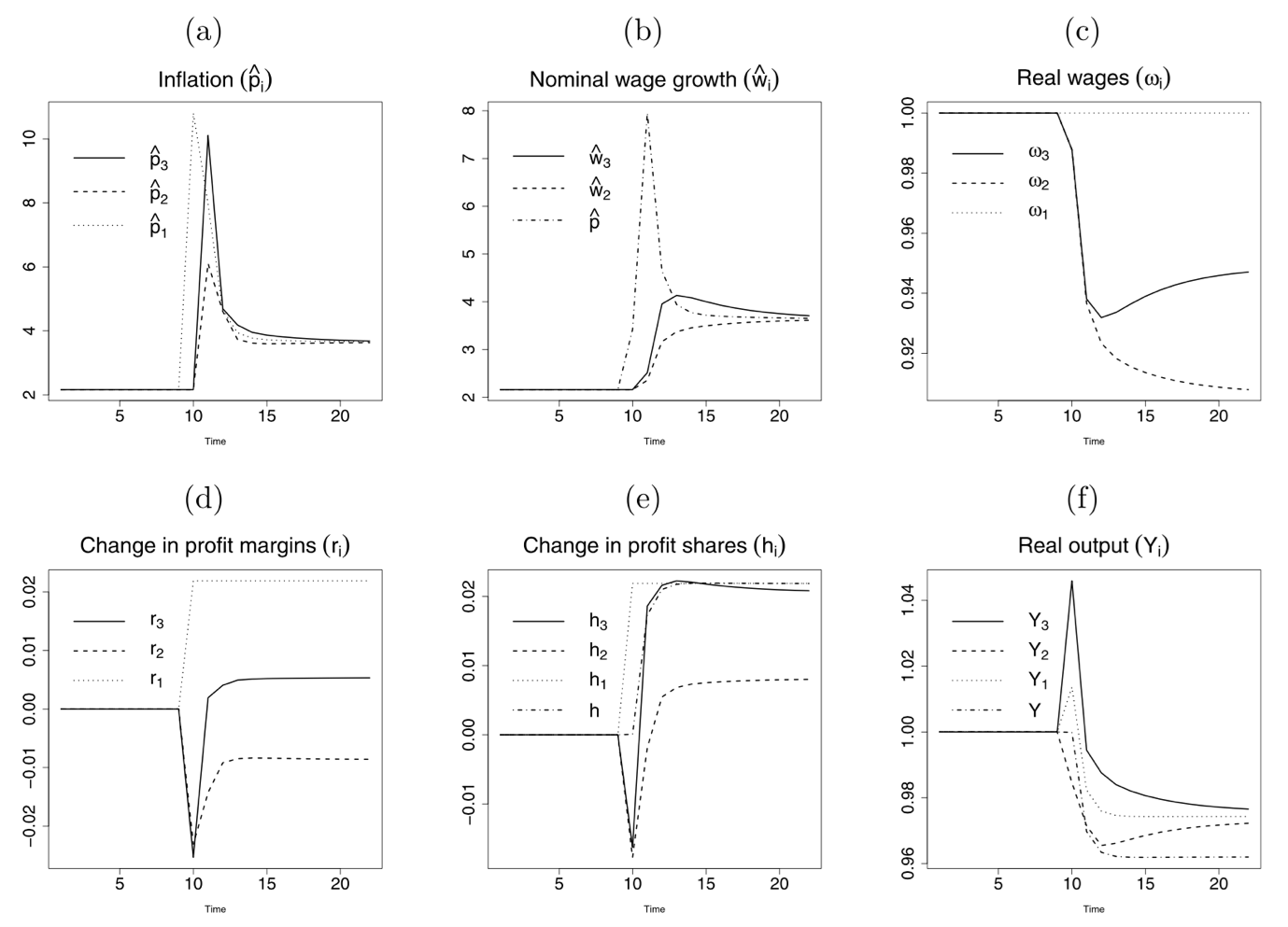

To simulate our model, we empirically calibrate its parameters using industry-level time-series data for the US. Figure 2 shows that the three shocks lead to a surge in inflation (panel a), followed by an increase in nominal wages due to conflict inflation (panel b). We call this a ‘price-wage’ spiral (as opposed to a ‘wage-price spiral’) as the stimulus for increased inflationary conflict comes from prices rather than wages. Real wages fall (panel c) while profit shares increase (panel e), implying a redistribution of income from labour to capital. Profit margins increase in the energy sector (due to the increase in energy prices) and in the goods sector (due to the positive demand and negative supply shock), while they decline in the services sector (panel d).

Figure 2 – Responses to a joint permanent increase in real energy prices, the demand for goods, and a reduction in potential output in the goods sector

Note: Sectors 1, 2, and 3 are the energy, services, and goods sectors, respectively. Shock occurs in period 10. Responses in panels a and b show growth rates. Responses in panels c and f are relative to their pre-shock values. Panels d and e show the percentage point change in profit margins and shares from the pre-shock values.

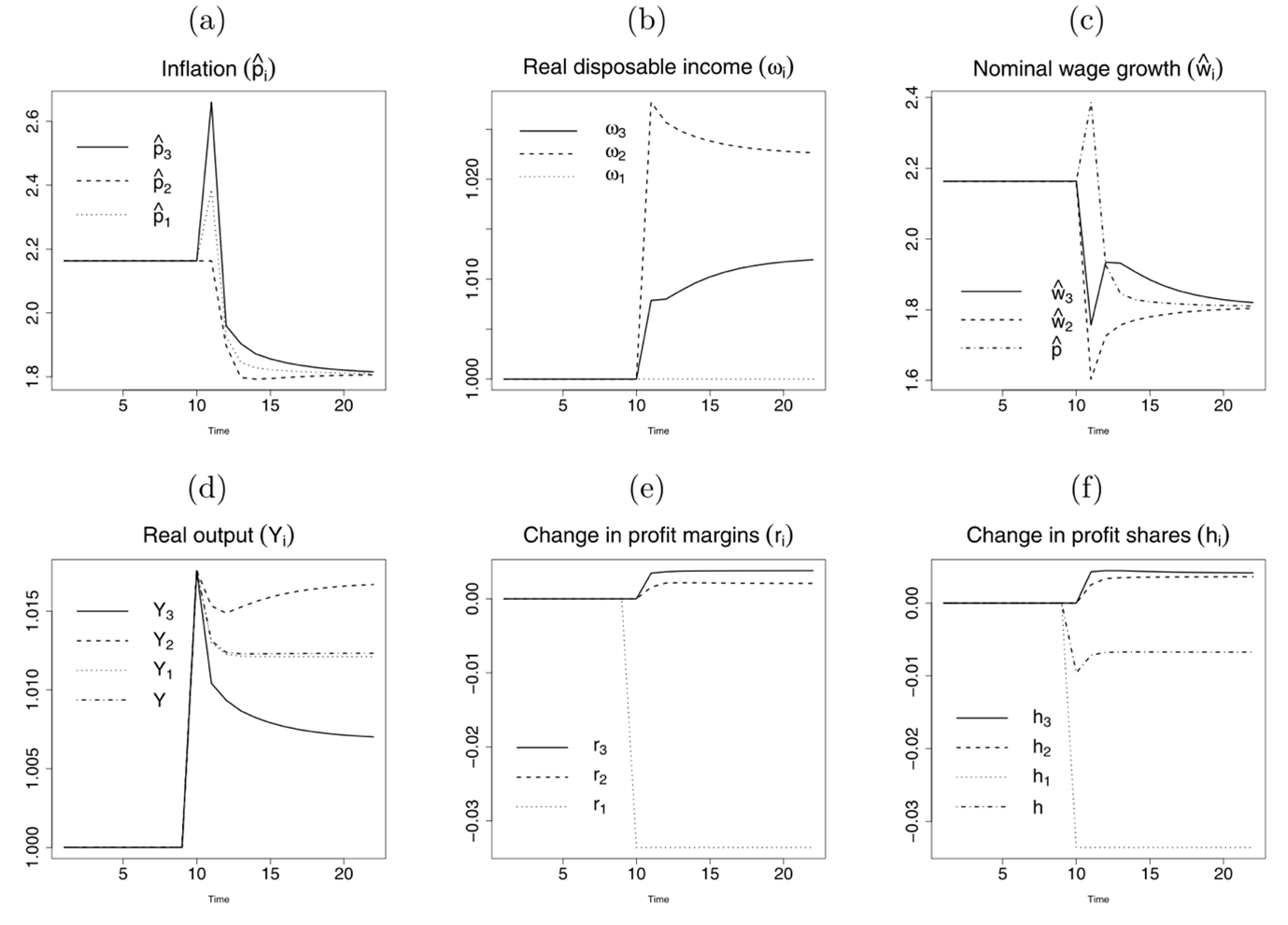

Figure 3 displays the effects of a windfall tax that transfers profits from the energy sector to workers. The increase in worker’s disposable income dampens distributional conflict and thereby lowers the inflation rate. It further leads to lower inequality and an economic expansion via higher consumption, which translates into a rise in employment. Unlike nominal wage restraint and aggregate demand contraction through monetary or fiscal policy, the transfer reduces inflation without reinforcing reductions in employment or increasing income inequality.

Figure 3 – Effects of a windfall tax and household transfers

Note: Sectors 1, 2, and 3 are the energy, services, and goods sectors, respectively. Shock occurs in period 10. Responses in panels a and b show growth rates. Responses in panels c and f are normalised by their initial steady-state values. Panels d and e show the percentage point change in profit margins and shares from the initial steady state.

Lessons for the ongoing inflation debate

What caused the surge in inflation? According to our analysis, higher inflation rates are triggered by two factors: higher energy prices, which result in increased profit margins in the energy sector, and shifts in consumer demand towards goods and supply bottlenecks, which generate rising markups in the goods sector. What about wage-price spirals? Our analysis suggests that the current situation is a price-wage spiral, which was triggered by increases in firms’ input costs and target profit margins. Thus, rising nominal wage demands must be seen primarily as a response to, rather than a source of, rising prices.

What about the much-discussed link between inflation and profits? A prominent argument is that, by raising prices beyond their increase in costs, firms amplify cost shocks. This is the case in our model in which firms have market power and charge a markup on their costs. A positive markup implies that firms always increase prices beyond their increase in costs and thus amplify these shocks. Moreover, sectors that additionally experience positive demand and/or negative supply shocks increase markups, thus exacerbating inflation caused by rising energy prices. Thus, our model provides a channel that explains rising profit margins and markups outside the energy sector – a factor that has been the topic of considerable debate. Some accounts have suggested that excess demand might not be necessary to explain rising markups if the energy cost shocks lead to a decline in the price elasticity of demand (Weber and Wasner, 2023; Donovan, 2023). However, in our framework markups increase endogenously in response to higher capacity utilisation (due to demand shocks or supply bottlenecks).

A second argument highlights that the recent inflationary episode contributed to an increase in income inequality. Data for the US, indeed, shows a decline in the labour share and thus a redistribution of income from labour to capital. Our model, which is calibrated to US data, reproduces this result. Importantly, our framework also shows that this increase in income inequality is not a necessary consequence of energy price shocks. A situation characterised by higher bargaining power for labour could increase the labour share. This highlights that who bears the brunt of the energy price shock depends on the institutional setting.

Summing up, redistributive policies can be effective at dampening inflation without reinforcing negative effects on employment and income inequality. This contrasts with contractionary aggregate demand policies. Our paper identifies a windfall tax as a promising tool. In addition to curbing inflation, the proceeds of a windfall tax would also dampen the effects of the cost-of-living crisis on lower-income households.

- This post is based on Energy price shocks, conflict inflation, and income distribution in a three-sector model, in Energy Economics and first appeared at LSE Business Review.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting

- Note: The post gives the views of its author, not the position USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3uWKNYx