It has become increasingly difficult for candidates in US congressional elections to be competitive without substantial campaign funding, much of which comes from donors. In new research, Mellissa Meisels and co-authors examine the role of candidates’ ideology on who donors decide to contribute to. Through a survey of 2018 congressional donors, they find that donors were less willing to contribute to candidates who were more moderate than them but were willing to contribute to candidates who were more or even much more extreme than they were. Donors were also more motivated to contribute to candidates running in the most competitive districts and against the opponents they disagree with the most.

It has become increasingly difficult for candidates in US congressional elections to be competitive without substantial campaign funding, much of which comes from donors. In new research, Mellissa Meisels and co-authors examine the role of candidates’ ideology on who donors decide to contribute to. Through a survey of 2018 congressional donors, they find that donors were less willing to contribute to candidates who were more moderate than them but were willing to contribute to candidates who were more or even much more extreme than they were. Donors were also more motivated to contribute to candidates running in the most competitive districts and against the opponents they disagree with the most.

Money has become increasingly important in US congressional elections. The total amount spent in House races rose to almost $10 billion in 2020, up from $3 billion in 2000, and winners spent over $2 million on average in 2020 compared to less than $850,000 in 2000. Although candidates ultimately need voters’ support to win election, they first need to raise major cash to wage a competitive campaign. The importance of fundraising in modern elections gives donors a potentially outsized influence in the political process.

Polarization and the role of ideology in donors’ decisions

A large body of academic work argues that contributions from individual donors worsen polarization among elected officials. Candidates’ need to raise money to run expensive campaigns can create financial incentives for them to cater to the wishes of donors. Donors’ positions on political issues are much more extreme than the positions of the general public, and donors also report that candidates’ ideology is very important in how they decide who to contribute to. Therefore, candidates might benefit financially from adopting more extreme positions that are more like donors’, contributing to elite polarization.

However, people who contribute to political campaigns also tend to be strong partisans who want to help their party win seats in Congress and defeat members of the opposite party. Strategic donors who prioritize getting the opposing party out of office and winning important elections, such as those in competitive districts, probably care less about the particular ideologies of their party’s candidates. If candidate ideology alone isn’t driving donors’ decisions, then candidates have less of a financial incentive to adopt donors’ extreme positions. Instead, donors would be merely responding to fixed characteristics of the election, making their role in polarization less clear.

Central to determining donors’ role in incentivizing polarization, then, is the question of the importance of candidate ideology to their decisions. In our research, we use an experiment to analyze the effect of candidate ideology on donations relative to the effect of other factors. We asked 7,000 people who gave to House candidates in the 2018 midterms to report their likelihood of contributing to a hypothetical candidate whose characteristics and electoral environment were randomly assigned. By varying the ideology, district competitiveness, opponent ideology and incumbency, and electoral viability of the hypothetical candidates, we can assess how strongly donors respond to changes in different aspects of House races.

Photo by Adam Nir on Unsplash

Donor behavior is shaped by district competitiveness, candidate and opponent ideology.

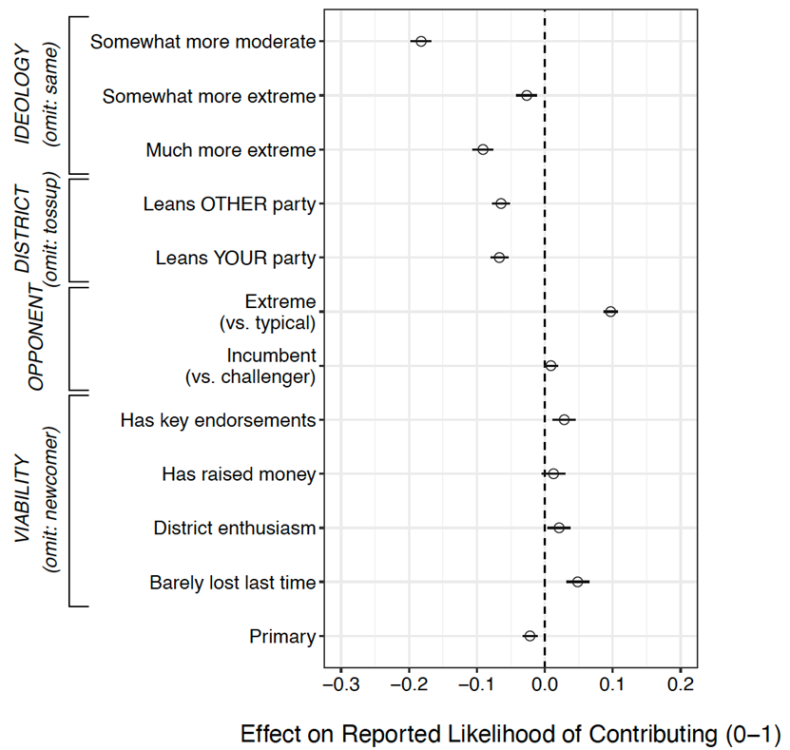

We find that donors’ reported likelihood of contributing to a House candidate changes the most in response to changes in descriptions of the candidate’s ideology, their opponent’s ideology, and their district’s partisan lean. As shown in Figure 1, donors were significantly less willing to contribute to a candidate described as somewhat more ideologically moderate than themselves compared to a candidate described as sharing their views. In contrast, however, donors barely penalize candidates described as somewhat more extreme than themselves. Even hypothetical candidates described as much more extreme than the donor are substantially more likely to receive a donation than candidates who are only somewhat more moderate. These results indicate that donors have a much higher tolerance for ideological extremism than for ideological moderation.

Figure 1 – Effect of Hypothetical Candidate Factors on Donor Likelihood of Contributing

In addition to the hypothetical candidate’s ideology, Figure 1 also shows that donors respond strongly to changes in the description of the hypothetical candidate’s district environment and opponent ideology. Donors are substantially less willing to contribute to a candidate running in a district that leans toward either party compared to a district that is a true “toss-up.” Candidates facing an extreme opponent were also much more likely to receive a donation than candidates described as facing a typical opponent. Donors appear motivated to contribute to candidates running in the most competitive districts and against the opponents they disagree with the most.

Taken together, our results suggest that the link between individual donors and polarization is not clear cut. Donors’ preferences and behavior are complex in a way that does not create straightforward incentives for candidates to adopt extreme positions. While their decisions are influenced by candidates’ ideologies, donors also respond strongly to candidates’ electoral environment. And although donors have a clear preference for candidates at least as extreme as themselves, they also prefer candidates running in competitive districts and against extreme opponents. On some level, then, political contributors are simply responding to fixed aspects of elections that candidates have no control over.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Giving to the Extreme? Experimental Evidence on Donor Response to Candidate and District Characteristics’, in the British Journal of Political Science.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3HOoGXN